i & kan 区别

THE REFLECTIVE EXPERIENTIAL ASPECT OF

MEANING OF THE AFFIX –i IN INDONESIAN

Francien Herlen Tomasowa

Universitas Brawijaya Malang

Abstrak

Penelitian ini bersifat kualitatif deskriptif dan bertujuan untuk

menjelaskan tentang aspek eksperiensial reflektif dari makna

akhiran –i dalam bahasa Indonesia.

Data yang digunakan berupa klausa yang mengandung

akhiran –i sebagaimana digunakan oleh penutur asli bahasa

Indonesia dan yang terdapat dalam buku-buku tatabahasa

Indonesia dan bahan lainnya, seperti koran, majalah dan buku

cerita anak yang tersebar luas di Indonesia dalam dua dasa-

warsa terakhir ini.

Hasil penelitian menunjukkan bahwa aspek eksperiensial

reflektif dari makna akhiran –i dalam bahasa Indonesia ber-

kaitan erat dengan macam kata dasar (base) serta macam pro-

ses di mana akhiran tersebut berada.

INTRODUCTION

The literature shows that there have been phonological, morphological and syntactical analyses of the characteristics of the verbal affix –i in Indonesian, among others by Edmond Tes (1957), Alisjahbana (1963, 1976, 1978), Abas (1971), Aman Singgih (1972), Keraf (1980), Samsuri (1976, 1985), Dardjowidjojo (1971, 1977, 1983) and Tampubolon (1977, 1978, 1983).

Tampubolon (1977:22) suggests that there are three approaches to affixation in the language: traditional (Mees, 1964; Alisjahbana, 19634), structural (Macdonald, 1976), and the one which he himself uses, namely semantic. Let us look at examples of each of these approaches below.

Sabaruddin Ahmad, as cited by Edmond Tes (1957:53) states that the affix –i functions as a verb-former. In functioning as a verb-former, the affix –i as a suffix forms a secondary base, and as part of the affixation per-i forms a tertiary base.

Alisjahbana (1976:88) claims that it can be assumed that the suffix –i makes from the object a kind of location; the object is static, e.g.: Ahmad melempari pohon itu dengan batu‘Ahmad is pelting the tree with stones’. On the other hand, the suffix –kan represents the object as something in movement, thus dynamic: Ahmad melemparkan batu kepada pohon itu ‘Ahmad is throwing stones at the tree’. Further he argues that the difference between menama kan and menama i in which nama means ‘name’, is that in the first case the person is changed from nameless to one with a name whereas in the second case a name is given to the person.

Francien H. Tomasawa

84Aman Singgih (1972:20) asserts that the affix –i , like the affix –kan , has two functions:

1) to make a word become a transitive verb; and/ or 2) to make a transitive verb (variant a) become ‘more transitive’ (variant b) such as in: a. Saya men dengar suara letusan mercon. ’I heard the cracker explosion.’ b. Saya men dengar kan siaran radio. ’I listened to the radio broadcast.’

As for the choice of –kan or –i , Singgih argues that the first is used whenever the object ‘moves’ while the latter when the object is ‘static’ or ‘does not move’. Some examples are: Ali mengirimkan surat ke Tokio. ‘Ali sent a letter to Tokio.” Ali mengirimi ibunya uang. ‘Ali sent his mother money.’

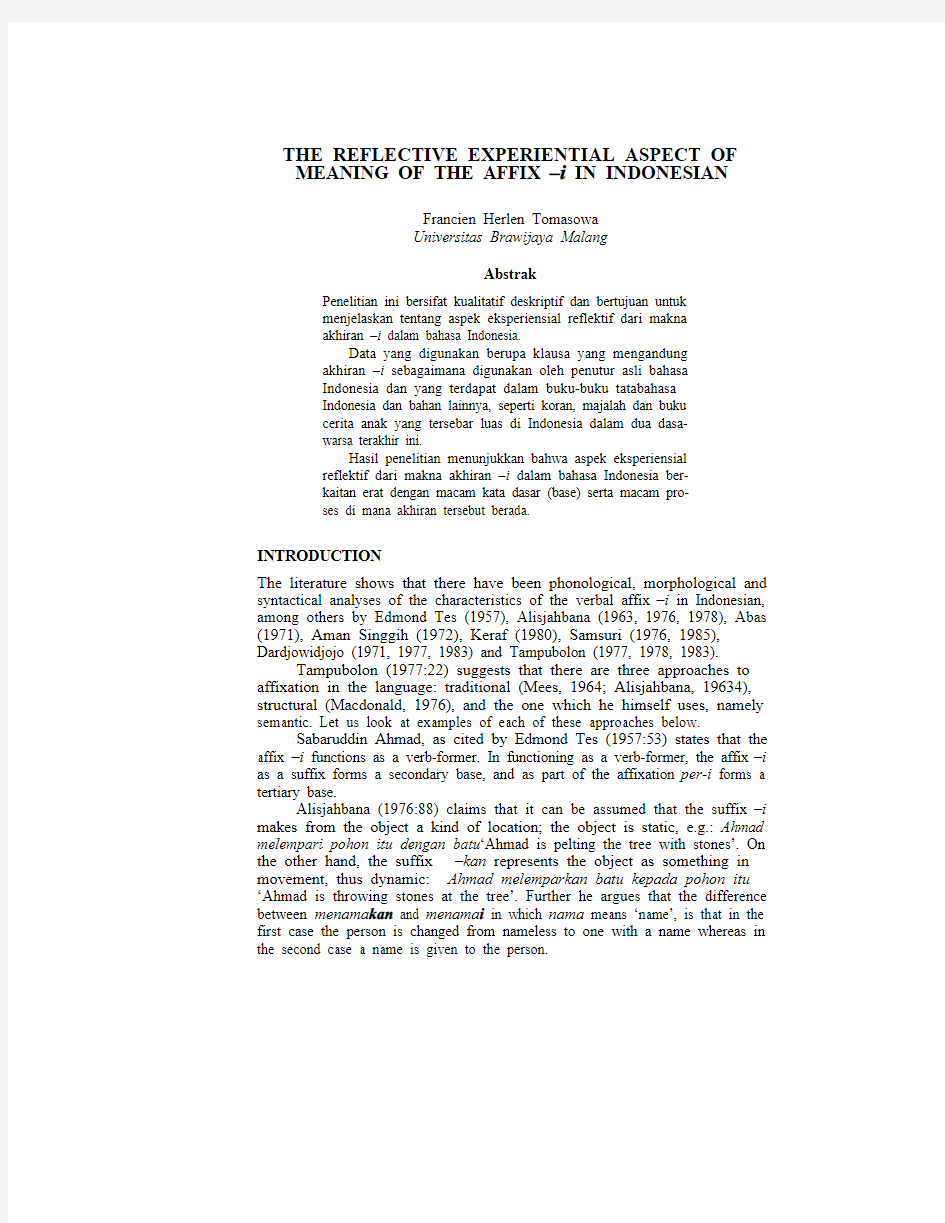

Whether the affix –i is a transitivizer, an intensifier or benefactive marker is idiosyncratic (Abas 1971:308). The given examples, which are admittedly not very illuminating, are presented in the table below. transitivizer ‘meng-ingin-I’ ‘me-‘ + want + ‘-i’ ‘meng-ingin-kan’ ‘me-‘ + want + ‘-kan’

benefactive marker ‘me-nama-I’ ‘me-‘ + name + ‘-i’ ‘me-nama-kan’ ‘me-‘ + name + ‘-kan’

intensifier ‘me-minjam-I’ ‘me-‘ + lend + ‘-i’ ‘meng-ajar-kan’ ‘me-‘ + teach + ‘-kan’

The literature also shows that some linguists who are non-native speakers of Bahasa Indonesia have shown interest in the function(s) of the affix –I in Indonesian. Among others are Pickering, A. (1974), Tcheckoff, C. (1978), Hopper, P.J. and Thompson, S.A. (1980), Prentice (1987) and Verhaar (1984). Hopper and Thompson (1980:261) compare Indonesian –kan and –i in terms of their semantic and distributional similarities. The two affixes can be found as a minimal pair (cf. Tjokronegoro 1968). They argue that the semantic difference between ‘Dia memanas i air’ and ‘Dia memanas kan air’ is that:

1. the action of heating in the first is gentler and more controlled than that in the latter; and

2. in the first the heat is brought to the water, whereas in the latter the water is placed over the heat.

Historically, they suggest that the two affixes may be derived from prepositions: -kan from the directional akan/ke- ‘to (a place); and –i from the locative ‘at’. As part of circumfixes with men- and memper-, the affix –i assigns locative role meaning to the Direct Object NP, frequently figurative, as in menduduki ‘to sit on, to occupy’; memperingati ‘to commemorate’; menghormati ‘to confer honour on, to honour’ (Verhaar 1984:6). As a derivational suffix (not the final portion of a circumfix), the affix –i , such as in memukuli ‘to hit repeatedly’ and menampari ‘to slap over and over again’ (see also Dardjowidjojo 1977:4)

Linguistik Indonesia, Tahun ke 25, No. 2, Agustus 2007

85

According to Prentice (1987:924) there is one phonologically determined constraint on the occurrence of the affix –i . It cannot concur with a base ending with the orthographic i. Some examples are memakai ‘to wear’ stemming from the base pakai ‘use’, and membenci ‘to dislike’ stemming from the base benci ‘dislike’. Verhaar (1984:6) argues that it is the ‘locative –i ’ that cannot be added to a base or stem already ending in the orthographic –i . He further expects that in earlier Malay the examples above were:

memaka ii instead of memaka i , and membenc ii instead of membenc i .

Kartomihardjo (1981:66) and Poedjosoedarmo (1982:70) assert that the affix –i in Indonesian and in Javanese has the following functions common to both languages:

1. formation of verbs referring to repetitive actions: e.g.: menghantami - ngantemi ‘to hit repetitively’ (Indonesian) (Javanese)

2. formation of a verb, the recipient of which is the place of the action. The recipient may be either inanimate: e.g.: menggulai - nggulani ‘to add sugar’ (Indonesian) (Javanese) or animate: e.g.: mengobati - nambani ‘to medicate’ (Indonesian) (Javanese)

3. formation of verbs the meaning of which is ‘become or be (Noun)’: e.g.: mengepalai ‘to head’

4. formation of verbs, the meaning of which is ‘make (adjective, number)’: e.g.: menyamai ‘to be alike’

In summary, the non-systemic functional approaches have revealed that the affix –i has seven functions/meanings:

1. verb-former (e.g. Sabaruddin Ahmad);

2. transitivizer (e.g. A. Singgih);

3. intensifier (e.g. Hopper and Thompson);

4. iterative/ repetitive (e.g. S. Dardjowidjojo; S. Kartomihardjo);

5. object becomes kind of location (e.g. S.T. Alisjahbana; S. Kartomihardjo);

6. become/ be (Noun) (e.g. S. Kartomihardjo); and

7. make Adjective/ Numeral (e.g. S. Kartomihardjo).

Despite those previous works on the affix, some problems concerning its grammatical meanings remain unsolved. Firstly, what in fact is the unifying function of the affix? Secondly, are the various functions assigned to the affix in complementary distribution to each other? Thirdly, is the generalization that an un-prefixed word containing the affix –i is a verb in its imperative form acceptable? And lastly, does the affix –i in menangisi ‘to cry (about)’ and menduduki ‘to sit (on)’ only function as a ‘transitivizer’?

Francien H. Tomasawa

861 METHOD OF RESEARCH

This study is descriptive qualitative by which the writer tries to explain the reflective experiential aspect of meaning of the verbal affix –i in Indonesian in detail. Two main sources of data were used for this descriptive study, namely, native speakers of Indonesian and written materials. For the purpose of investigating the functional characteristics of the verbal affix –i in Indonesian, some Indonesian tertiary level teaching staffs that have all been brought up and educated in Indonesian since childhood were used as informants and were consulted to judge the acceptability of certain data. Each informant was asked to make sentences containing the affix –i from which the 400 sentences gathered were used as a bank to refer to in describing the functional characteristics of the affix. The written data used comprised textbooks on the grammar of Indonesian (Alisjahbana 1963, Moeliono 1967, Macdonald and Soenjono 1967, Macdonald 1976, Sarumpaet 1977, Badudu 1980, Keraf 1980 and Harsana 1982), some widely distributed Indonesian newspapers (Kompas and Surya) and magazines (Tabloid, Intisari, Basis, Matra and Femina) and children’s stories published in the last two decades. These written sources are chosen for three reasons. Firstly, the language used is both contemporary and used by educated people. Secondly, they are largely circulated in the country, and thirdly, they cover various text types. The newspapers and the first magazine mentioned contain socio-economic and political topics; Intisari and Basis contain scientific topics, whereas Matra and Femina are intended for readers of a certain sex, the first is for male and the latter for female readers. Given the range of fields, including the children’s stories, it is considered that the data are sufficiently representative for the investigation. The data were analyzed using the systemic functional model of grammar postulated by Halliday (1967, 1976, 1981, 1985). The theory underlying this grammar is a theory of meaning as choice: a language or any other semiotic system is interpreted as networks of interlocking options.

2 FINDING AND DISCUSSION

The result of perceiving the meaning of the verbal affix –i in Indonesian from systemic functional model of grammar postulated by Halliday (1967, 1976, 1981, 1985), which interprets a language or any other semiotic system as networks of interlocking options is as follows. In terms of experiential meaning, processes in Indonesian can be distinguished into five types: those of ‘doing’ called material processes , such as makan ‘eat’, pukul ‘hit’, tumbuh ‘grow’; those of ‘sensing’ called mental processes , such as melihat ‘see’, mencintai ‘to love’, mengenali ‘to recognize’; those of ‘being’ called relational processes , such as adalah ‘to be’, ternyata ‘to turn out to be’; those of ‘verbalizing’ called verbal processes , such as berkata ‘to say’; and those of ‘existing’ called existential processes , such as ada ‘to exist’ (see also Tomasowa, 1989, 1992). Furthermore, Tomasowa states that the types of processes vary in terms of the type of base forming the Process. In general, material Processes may stem from verbal, nominal, adjectival, adverbial, bound, multi-functional or

Linguistik Indonesia, Tahun ke 25, No. 2, Agustus 2007

87

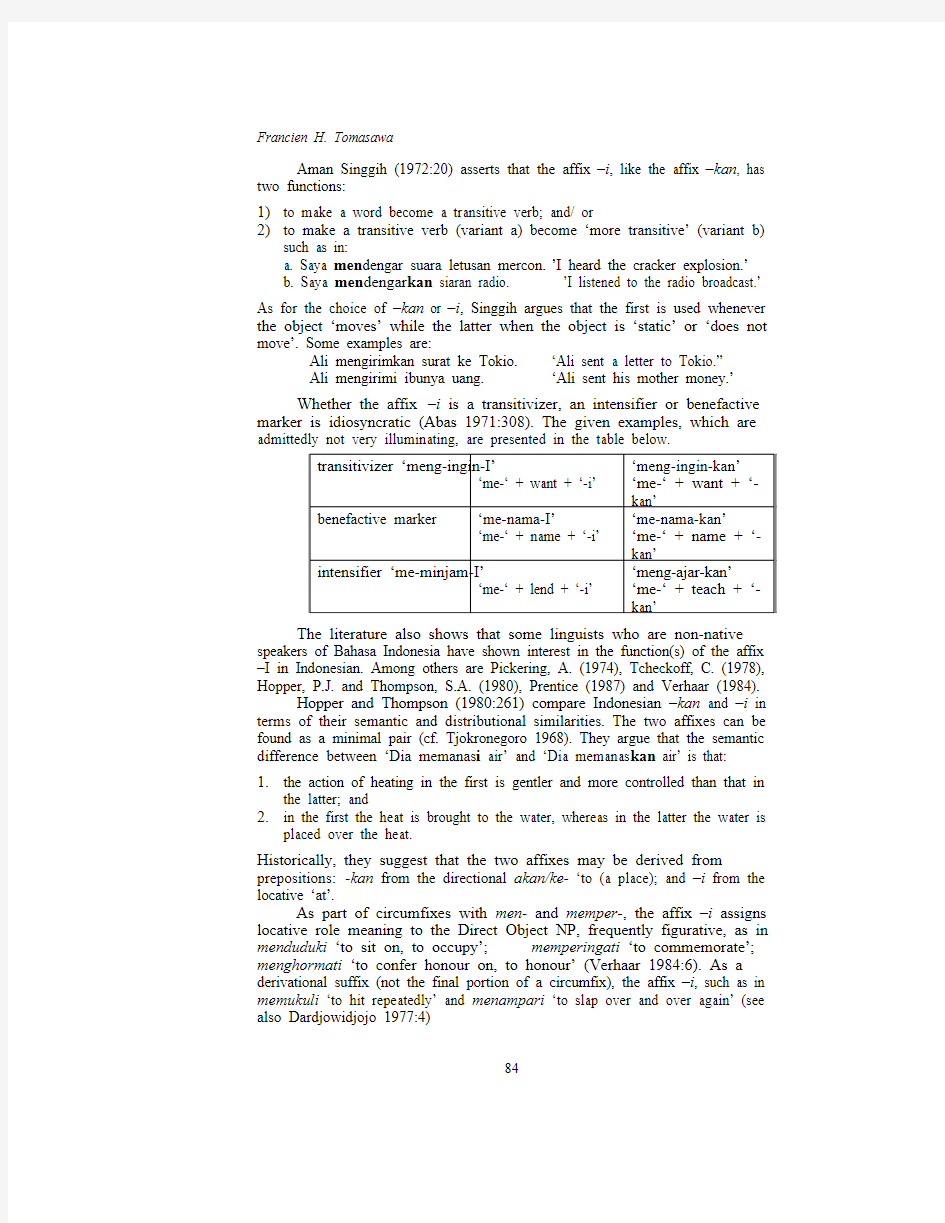

structural word bases. Mental Processes may stem from verbal, nominal, adjectival, adverbial, bound, multi-functional as well as minor-class bases. Relational Processes may stem from verbal and nominal bases. Verbal Processes may stem from verbal and multi-functional bases whereas the existential Process stems from an adjectival base. Table 1 below is the summary of the type of base forming the Process of an Indonesian dispositive clause. Table 1. The type of base forming the type of Process in an Indonesian dispositive clause.

Type of base forming the Process Type of dispositive Process V N Adj Adv B MF MC

material

Doing √ √ × √ √ √ √

Making × × √ × × × ×

Animal natural √ × × × × × ×

Inanimate natural √ × × × × × ×

Mental

Perception √ × × × √ √ √

Positive inner feelings √ √ √ × √ √ ×

Negative inner feelings × √ √ × √ × ×

cognition √ × √ √ √ × ×

Relational Equational × √ × × × × ×

Intensive attributive √ × × × × × ×

Circumstantial attributive × × × × × × ×

Possessive attributive √ √ × × × × ×

Adversative attributive × × × × × × ×

Verbal Statement × × × × × √ ×

Question √ × × × × × ×

Command √ × × × × × ×

offer √ × × × × × ×

Existential × × × × × × ×

Notes: √ = present

N = nominal B = bound × = absent

Adj = adjectival MF = multi-functional V= verbal Adv = adverbial MC = minor-class

2.1 Distribution of the Affix –i

In terms of the distribution of the affix -i across dispositive processes, the circumstantial, adversative attributive and existential processes do not bear the affix –i whereas all the other processes in the language do. Furthermore, the affix –i appears attached to a certain lexical base to form a Process. The affix can occur by itself or as part of the larger verbal affixation (me-)+-i (or its receptive variants: ter-+-i or di-+-i ). Thus the description of the verbal affix -i

Francien H. Tomasawa

88in this study covers the functions of the affix by itself and as part of a larger affixation. In its grammatical function as an internal causative marker, the affix –i may function by itself or as part of a larger affixation, and may be found in attachment to:

-

a verbal base; e.g.: duduk ‘to sit’ in men duduk i ‘to sit on’, ‘to occupy’ -

a bound base: e.g.: lucut in me lucut i ‘to disarm’ -

a nominal or an adjectival base: e.g.: sampul ‘cover’ in me nyampul i ‘to cover, to wrap’ panas ‘hot’ in me manas i ‘to heat’ -

a multi-functional base: e.g.: jalan ‘road or to walk’ in men jalan i ‘to walk, to spend’ - an adverbial or a minor class base: e.g.: dapat ‘can’ in men dapat i ‘to find’ serta ‘with, along with’ in me nyerta i ‘to accompany, to participate’

The affix may be attached to a verbal or nominal base in material, mental and verbal processes. When attached to a base other than the two mentioned before, it can be found in material and mental processes only. Chung (1978:338) calls the affix “the transitivising suffix –i ”. She refers to examples such as Guru itu memasuki rumah kecil . meaning ‘The teacher entered a small house’ as if the affix is involved only in the transitive part of the statement. In fact, as part of the verbal affixation (me-)+-i , the affix –i in the above clause functions as an ‘internal causative marker’ in the ergative semantic model, and as an ‘indicator that the Goal is the location of the action’ in the transitive semantic model as shown below: Guru itu memasuki rumah kecil.

transitive Actor Process Goal

ergative Medium Process Range

teacher that to enter house small ‘The teacher entered a small house’

In terms of the types of base the affix –i is attached to, the data show that it may be attached to a verbal base; a bound base; a nominal or an adjectival base; a multi-functional base; an adverbial or a minor class base. Whereas the affix is attached to a verbal base or a nominal base in material, mental, relational (equational, intensive and possessive) and verbal processes; it is attached to other types of base in material and mental processes of the language. The distribution of the affix –i across the processes is shown in Table 2.

Linguistik Indonesia, Tahun ke 25, No. 2, Agustus 2007

89

Table 2. Distribution of the Affix –i among Processes in Indonesian.

Distribution in relation to type of Process base Type of Process Distribution of affix -i 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

1 material :

action – doing √ √ √ × √ √ √ √

action – making √ × × √ × × × ×

natural - animate √ √ × × × × × ×

natural - inanimate √ √ × × × × × ×

2 mental :

perception √ √ × × × √ √ √

inner feeling - positive √ √ √ √ × √ √ ×

inner feeling - negative √ × √ √ × × × ×

cognition √ √ √ √ √ √ × ×

3 relational :

equational √ × √ × × × × ×

attributive - intensive √ √ × × × × × ×

attributive - circumstantial × × × × × × × ×

attributive - possessive √ √ √ × × × × ×

attributive - adversative × × × × × × × ×

4 verbal :

statement √ × × × × × √ ×

question √ √ × × × × × ×

command √ √ × × × × × ×

offer √ √ × × × × × ×

5 existential × × × × × × × × Notes: √ = present 3 = adjectival base 7 = minor-class base

× = absent 4 = adverbial base

1 = verbal base 5 = bound base

2 = nominal base 6 = multi-functional base

Table 2 shows that in terms of type of process, the affix –i can be observed in all process types except for the existential processes. Moreover, its presence is related to the type of base forming the Process. In natural material, intensive attributive, question, command and offer processes, the affix –i is usually attached to a verbal base. In equational processes it is attached to a nominal base, whereas in making processes, the affix is attached to an adjectival base. In possessive attributive processes, the affix is attached to a verbal or nominal base. In doing material processes it may be attached to a verbal, nominal, adverbial, bound, multi-functional or minor-class base. In positive inner feeling processes, the affix is attached to a verbal, nominal, adjectival, bound or multi-functional base. In negative inner feeling processes, the affix –i is attached to a nominal, adjectival or bound base. In mental processes of cognition it may be attached to a verbal, nominal, adjectival or bound base. In statement processes it is found attached to a multi-functional base.

Francien H. Tomasawa

902.2 Functions of the Affix –i

The verbal affix –i in Indonesian has two unifying grammatical functions: a dispositive marker and an internal causative marker. In addition to these unifying functions, it also carries some specific grammatical functions which differ from process to process, depending on the type of base it is attached to in forming the Process of a clause. The functions of the affix –i can be distinguished into unifying , which apply to all types of process regardless of the type of base forming the Process of the clause, and specific , which depend on the type of base it is attached to in forming the Process. The unifying and specific functions of the affix –i are shown in Table 3. Table 3. Functional Characteristics of the Affix –i in Processes in Indonesian

Types of function of the affix unifying specific types of dispositive processes types of Process base 1 234 5 6 7 8 9

a. material V √ ××√√ × × × ×

N √ √×√× √ √ × ×

Adv √ √××× × × × √B √ √×√× × × × ×

MF √ ××√√ × × × ×

doing MC √ √××× × × × ×

making Adj √ √×√× × × √ ×

animate natural V √ ××√√ × × × ×

inanimate natural V √ ××√√ × × × ×

b. mental V √ √√×√ × × × ×

B √ √√×× × × × ×

MF √ √××× × × × ×

perception MC √ √××× × × × ×

V √ ×√×√ × × × ×N √ √××× × × × ×

Adj √ √××× × × × ×

B √ √××× × × × ×

positive. inner feelings MF √ √√×× × × × ×

N √ √√×× × × × ×Adj √ √××× × × × ×

negative inner feelings B √ √××× × × × ×

V √ ×√×× × × × ×Adj √ √××× × × × ×

Adj √ √××× × × × ×

cognition

B √ √××× × × × ×

Linguistik Indonesia, Tahun ke 25, No. 2, Agustus 2007

91

Table 3. Functional Characteristics of the Affix –i in Processes in Indonesian

Types of function of the affix unifying specific types of dispositive processes types of Process base 1 234 5 6 7 8 9

c. relational equational N × √××× × × × ×intensive attributive V × √××× × × × ×

circumstantial attributive

× × ×××× × × × ×V × √××× × × × ×possessive attributive N × √××× × × × ×

adversative attributive

× × ×××× × × × ×d. verbal statement MF √ √××× × × × ×question V √ √××× × × × ×

command V √ √√×√ × × × ×

offer V √ √××× × × × ×

e. existential × × ×××× × × × ×Notes: √ = applicable V = verbal

× = not applicable N = nominal

1 = internal causative marker Adj = adjectival

2 = Process-former Adv = adverbial

3 = intensified Process marker MF = multi-functional

4 = Goal is location of action marker MC = minor-class

5 = repetitive Process marker

6 = addition of base to Goal indicator

7 = deletion of base to Goal indicator

8 = base is Attribute of Goal indicator

9 = temporal/ spatial relationship between Actor and Goal indicator

Let us now look at the unifying and specific functions of the verbal affix –i in turn.

2.2.1 Unifying Functions

Table 3 shows that the affix –i has two unifying functions, namely as a dispositive marker and an internal causative marker, whenever the clause is Process focused (material, mental and verbal), regardless of the type of base forming the Process. In terms of the transitive semantic model of the clause, the affix –i is found only in dispositive processes and is therefore regarded as a dispositive marker . A second participant is obligatory in a clause containing the affix –i as shown below:

Francien H. Tomasawa

92 Ibu memanasi nasi.

transitive Actor Process Goal

ergative Medium Process Range

‘Mother warmed the rice up’

*Ibu memanasi. transitive Actor Process ergative Medium Process Mother warm up

In terms of the ergative pattern of clause organization, the affix –i functions as an internal causative marker (‘internal’ after Itkonen, 1983). Note that with this affix, the second participant is the Range of the clause. Therefore, the affix –i can be regarded as an indicator that the second participant in that particular clause is the Range (not the Medium) of the clause. By contrast, the affix –kan in Indonesian is an external causative marker . It can be regarded as a marker that the second participant in that clause is the Medium of the clause, as can be seen in the following mental processes (compare the two clauses below). Pangeran menyenang i Bawang Putih.

transitive Actor Process Goal

ergative Medium Process Range

‘The prince likes Bawang Putih’ Pangeran menyenang kan Bawang Putih.

transitive Actor Process Goal

ergative Medium Process Range

‘The prince makes Bawang Putih happy.’

In other words, there are two ways of viewing the unifying function of the verbal affix –i in this case:

1. transitively, it serves as a dispositive marker, and

2. ergatively, it serves as an internal causative marker.

In addition to this unifying function, the verbal affix –i also shows some specific grammatical functions as elaborated in the following.

2.2.2 Specific Functions

Depending on the type of base forming the Process of the clause, Table 3 shows that the affix –i may have one or more of the following specific functions:

-

Process-former; -

intensified Process marker; -

Goal = location of action indicator; -

repetitive Process marker; - addition of base to Goal indicator;

Linguistik Indonesia, Tahun ke 25, No. 2, Agustus 2007

93

-

deletion of base to Goal indicator; -

base = Attribute of Goal indicator; -

temporal relationship between Actor and Goal indicator; and - spatial relationship between Actor and Goal indicator.

In explaining the function of the affix as a Process-former (‘verb-former’), Sabarrudin Ahmad (as cited by Edmond Tes, 1957:53) fails to show the restrictions of this function. Tomasowa (1992) reveals that this function is mainly related to the non-verbal type of base forming the Process, as in material and mental processes in Indonesian. However, there are processes in which a verbal base by itself is still unacceptable in the language, such as intensive attributive and verbal processes. Here the base needs the affixation me-+-i or –i to become acceptable. Take the intensive attributive process, for example: a. *Cerita itu kena seekor tikus. b. *Cerita itu kena i seekor tikus. c. *Cerita itu me ngena seekor tikus. d. Cerita itu me ngena i seekor tikus.

transitive Carrier Process Attrubute ergative Medium Process Range ‘The story is about a mouse.’ The verbal base kena ‘to hit’ has to be affixed by me-+-i to become the acceptable Process me ngena i ‘to concern, be about’ of the intensive attributive process. Similarly counts for the verbal base tawar ‘to bargain’ which has to be put in affixation with either –i or me-+-i to become the acceptable Process tawar i or me nawar i ‘to invite’ of the verbal process below:

a. *Ina tawar Titut untuk ikut piknik.

b. *Ina menawar Titut untuk ikut piknik.

c. Ina tawar i Titut untuk ikut piknik.

d. Ina me nawar i Titut untuk ikut piknik.

transitive Sayer Process Recipient Verbiage ergative Medium Process Beneficiary Range ‘Ina invited Titut to join the picnic.’

Hopper and Thompson (1980) state that the affix –i is an intensifier. Using the systemic functional approach, this study has nevertheless revealed that the function of the affix –i as an intensified Process marker (‘intensifier’ after Hopper and Thompson) is strongly related to both the type of base forming the Process and the clause as a whole. In most instances, this function co-occurs with a verbal base forming the Process (perception, positive inner feeling, cognition and command verbal processes). In forming the Process, the affix –i may co-occur with a bound base (perception processes), a multi-functional base (positive inner feeling processes) or a nominal base (negative inner feeling processes) forming the Process. From the way S.T. Alisjahbana (1976) and S. Kartomihardjo (1981) argue that the affix –i shows that the Object becomes a kind of location, it might be assumed that this function applies to all types of process. However,

Francien H. Tomasawa

94the present study argues that this function applies only to the material processes in Indonesian. Furthermore, this function does not depend on the type of base forming the Process of the clause. That the affix –i is iterative/ repetitive has been mentioned in earlier studies such as those by Dardjowidjojo (1977), Kartomihardjo (1981) and Poedjosoedarmo (1982). More delicately, this study reveals that the function of this affix as a marker of repetition of the Process is closely related to both the type of base forming the Process and the type of process as a whole. The function applies to material, mental and verbal processes only. Among the processes mentioned, the affix –i is mostly attached to a verbal base such as in doing, animate natural, inanimate natural, perception, positive inner feeling and command verbal processes. It can also be attached to a multi-functional base such as in doing processes. In summary, the functions of the affix –i that are highly related to the type of base forming the Process and the type of process as a whole are as an indicator that:

-

there is addition of base to/ from the Goal; -

there is deletion of base to/ from the Goal; -

there is temporal relation between Actor and Goal; -

there is spatial relation between Actor and Goal; or - the base becomes the attribute of the Goal.

The first four functions apply only to doing material processes, in which addition or deletion of base to/ from the Goal co-occurs with the nominal base forming the Process while the temporal/ spatial relation between Actor and Goal co-occurs with the adverbial base forming the Process of the clause. 3 CONCLUSION

This article has tried to answer the unsolved questions about the grammatical meanings of the verbal affix –i in Indonesian using the systemic functional approach. The findings of this study assure that the functional characteristics of the affix –i in the transitive system of Indonesian are mainly determined not only by the type of process as a whole but also by the type of base forming the Process of the clause in which the affix occurs.

Linguistik Indonesia, Tahun ke 25, No. 2, Agustus 2007

95

REFERENCES

Abas. 1971. Linguistik Deskriptif dan Nahu Bahasa Melayu. Kualalumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. Alisjahbana, S.T. 1963. Tatabahasa Baru Bahasa Melayu/ Indonesia. Kualalumpur: Bi-Karya Publ. Ltd. Vol.2. _____________ 1976. Language Planning for Modernization, The Case of Indonesian and Malaysian. Paris: Mouton. _____________ 1978. The Concept of Language Standardization and Its Application to the Indonesian Language, in PCSAL , Perez et al (Eds.) Pacific Linguistics Series C No.47. p. 19-41. Badudu, J.S. 1980. Pelik-pelik Bahasa Indonesia (Tatabahasa). Bandung: Pustaka Prima. Chung, S. 1978. Stem Sentences in Indonesian, in Second International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics Proceedings. Fascicle 1. S. A. Wurm & Lois Carrington, Eds. Pp. 335-65. Dardjowidjojo, S. 1971. The meN-, meN-kan, and meN-i Verbs in Indonesian, in The Philippines Journal of Linguistics. Vol. 1, No. 1, 1971. _____________ 1977. Sentence Patterns of Indonesian. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii. _____________ 1977a. Sekitar Masalah Awalan Ber- dan Me-, in Bahasa and Sastra . Vol. 3/1/1977, pp. 2-10. _____________ 1977b. The Semantic Structures of the Adversative ke-an Verbs in Indonesian. Paper presented at the Austronesian Symposium, University of Hawaii, August 1977. _____________ 1983. Beberapa Aspek Linguistik Indonesia. Jakarta: Penerbit Djambatan. Edmond - Tes. 1957. Fungsi dan Arti Imbuhan, in Majalah Medan Bahasa no.8, Th.VII, Agustus 1957, pp. 17-20. Halliday, M.A.K. 1967. Notes on Transitivity and Theme in English, in Journal of Linguistics . Graet Britain. Vols.1,2. _____________ 1976. System and Function in Language. G.R. Kress (Ed.) London: Oxford University Press. _____________ 1981. Options and Functions in the English Clause, in Readings in Systemic Linguistics , Halliday & Martin (Eds). Lonmdon: Batsford Academic and Educational Ltd. _____________ 1985. An Introduction to Functional Grammar . London: Edward Arnold Ltd. _____________ 1988. On the Ineffability of Grammatical Categories, in Linguistics in a Systemic Perspective, J.D. Benson, M.J. Cummings, W. S. Greaves (Eds.). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publ. Company. Harsana, F.X. 1982. Tata Kalimat Bahasa Indonesia. Solo: Tiga Serangkai. Hopper, P. & Thompson, S.A. 1980. Transitivity in Grammar and Discourse, in Language 56.2 pp. 251-299. Itkonen, E. 1983. Causality in Linguistic Theory . Sydney: Croom Helm. Kartomihardjo, S. 1981. Ethnography of Communicative Codes in East Java . Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. Series D No. 39. Keraf, G. 1980. Tatabahasa Indonesia untuk Sekolah Lanjutan Atas . Ende: Penerbit Nusa Indah.

Francien H. Tomasawa

96Macdonald, R. Ross. 1976. Indonesian Reference Grammar. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. Mees, C.A. 1969. Tatabahasa dan Kalimat. Kualalumpur: University of Malaya Press. Moeliono, A. 1967. Suatu Reorientasi dalam Tatabahasa Indonesia, in Bahasa dan Kesusasteraan Indonesia Sebagai Tjermin Manusia Indonesia Baru. Djakarta: Gunung Agung. pp.45-68. Pickering, A. 1974. An Introduction to Indonesian Verb Morphology – A Transformational Approach. Unpublished Litt. B. dissertation. Poedjosoedarmo, S. 1982. Javanese Influence on Indonesian . Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. Series D No38. Prentice, D.J. 1987. Malay (Indonesian and Malaysian), in The World’s Major Languages , Bernard Comrie (Ed.). London: Croom Helm. Samsuri. 1976. Kesejajaran antara Me-I dan Men-kan, in Bahasa dan Sastra. Vol II/2 th. 1976. pp.33-9. _______ 1985. Tata Kalimat Bahasa Indonesia . Jakarta: Sastra Hudaya. Sarumpaet, J.P. 1977. The Structure of Bahasa Indonesia. Melbourne: Sahata Publications. Singgih, A. 1972. Menuju Bahasa Indonesia Umum. Bandung: Pustaka Jaya. Tampubolon, D.P. 1977. Hambatan-hambatan Semantik atas Terjadinya Afiksasi meN-, in Bahasa dan Sastra. Vol. 3/2/1977. pp. 22-31. _______________ 1978. Tipe-tipe Semantik Kata-kata Kerja Bahasa Indonesia Kontemporer . Medan: Tim Penelitian FKSS-IKIP Medan. _______________ 1983. Verbal Affixation in Indonesian: A Semantic Exploration . Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. Tcheckoff, C. 1978. Typology and Genetics: Some Syntactic Conclusions that can be Drawn from a Functional Comparison between Indonesian Verbal Suffix –I and Tongan –I, in SICAL Proceedings , S.A. Wurm & Lois Carrington, Eds. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. Fascicle 1, pp.367-82. Tomasowa, F. H. 1989. Bidirectionality of Processes in Contemporary Bahasa Indonesia: a systemic functional perspective, in ARAL vol. 12/1 pp.224-44. _____________ 1992. Transitivity in Contemporary Bahasa Indonesia: A Systemic Functional Perspective Using the Verbal Affix –I as a Test Case . Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Macquarie University, Sydney Australia. Verhaar, J.W.M. 1984. Affixation in Contemporary Indonesian, in NUSA , vol. 18/1984. Jakarta.

同步电机与异步电机区别说的非常好

同步电机与异步电机区别说的非常好 集团档案编码:[YTTR-YTPT28-YTNTL98-UYTYNN08]

一、同步电机和异步电机在设计上的不同: ①同步与异步的最大区别就在于看他门的转子速度是不是与定子旋转的磁场速度一致,如果转子的旋转速度与定子是一样的,那就叫同步电动机,如果不一致,就叫异步电动机。。。 ②当极对数一定时,电机的转速和频率之间有严格的关系,用电机专业术语说,就是同步。异步电机也叫感应电机,主要作为电动机使用,其工作时的转子转速总是小于同步电机。 ③所谓“同步”就是电枢(定子)绕组流过电流后,将在气隙中形成一旋转磁场,而该磁场的旋转方向及旋转速度均与转子转向,转速相同,故为同步。 异步电机的话,其旋转磁场与转子存在相对转速,即产生转距。 二、为什么会同步,为什么会不同步呢? 同步电机和异步电机的定子绕组是相同的,主要区别在于转子的结构。同步电机的转子上有直流励磁绕组,所以需要外加励磁电源,通过滑环引入电流;而异步电机的转子是短路的绕组,靠电磁感应产生电流。相比之下,同步电机较复杂,造价高。 同步和异步电机均属交流动力电机,是靠50Hz交流电网供电而转动。异步电机是定子送入交流电,产生旋转磁场,而转子受感应而产生磁场,这样两磁场作用,使得转子跟着定子的旋转磁场而转动。其中转子比定子旋转磁场慢,有个转差,不同步所以称为异步机。而同步电机定子与异步电机相同,但其转子是人为加入直流电形成不变磁场,这样转子就跟着定子旋转磁场一起转而同步,始称同步电机。 简单的说就是:异步电机的转子上没加直流励磁电流,同步电机的转子上加了一个直流励磁电流使转子的转速与定子与转子切割产生的磁场转速一致。 三、同步发电机转子为什么要通入直流励磁电流,而不通入交流励磁电流? 按工频50HZ考虑,转子通入直流励磁电流,可在定子绕组中感应出50HZ电势。 转子通入交流励磁电流后,可分解为正向与反向两个旋转磁场,正向旋转磁场旋转速度与转子旋转速度迭加,在定子绕组中感应出100HZ电势;反向旋转磁

议论文考点阅读:考点一--把握、区别论点与论题

议论文考点阅读:考点一把握、区别论点与论题 【考点2011】 ①本文的中心论点是什么?(2011年安顺市) 《让有些话穿耳而过》 ②本文论述的主要观点是什么?(2011年佛山市)《财富与幸福》 【考点讲析】 (一)论题的判断 (难易程度:★★) 论题就是议论类文章中的“话题”,所谓“话题”就是谈话的中心,对于议论类文章而言就是作者论述的对象或范围。议论类文章的“论题”在形式上一般是一个词语、短语,甚至是表示一个现象的一小句话。论题是组成论点的一个关键部分,但不是一个论点。论题一半在文章题目或者开头出现。 (二)论点 (难易程度:★★) 1.论点:就是作者在文中对论题(所论述问题)的见解和主张,是文章的灵魂。一篇文章只有一个中心论点,某些文章还围绕中心论点提出几个分论点,两者是从属关系。 注意: (1)中心论点的位置:①在标题中;②在文章开头;③在文章中间;④在文章结尾;⑤在文章中没有明显的语言表述中心论点,要通过概括全文获得。 (2)中心论点的特点:①是一个表示肯定陈述语气的判断句;②要有明显的倾向性,并旗帜鲜明地表述观点;③语言简洁;④有些文章既有分论点,也有中心论点,但是只有一个中心论点。 2.围绕“论点”,归纳命题形式(难易程度:★★) ①“中心论点”和“分论点”的区别? ②“中心论点”和“论题(话题)”的区别; ③文章(段)的“论点”是什么?如何找到它? 【考点测试】 一、 2011年辽宁本溪市特色是成功的催化剂 特色是成功的催化剂 ①提到“特色”一次,就必然使我们想到“特别”“特殊”“与众不同”等词语。从艺术上有特色的作品,到生活中有特色的服饰、语言;从商业上有特色的产品,到管理上有特色的服务、教育等等。这些都会让我们深刻地认识到:只有有特色才会被认可,才会为成功打下良好的基础。 ②纵观古今,因自己的特色而受益,因受益而迈向成功的例子比比皆是。 ③著名画家郑板桥,其书法作品也很闻名,被称为“板桥体”,就是因为他的书法有自身的特色,是独一无二、无可替代的。设想郑板桥当初如果只是用隶书或行楷,即使模仿名人的笔迹再出色,再逼真,恐怕也不会在书法界有如此大的成就吧! ④再如现在的餐饮行业,竞争很激烈,随时有被时代淘汰的可能。据网上统计,业绩好、受顾客欢迎的,大多数是主题餐厅。有在一片黑暗中进食的餐厅,有在店内装饰上体现民族风格的餐厅,更有专门为白领女性提供免费营养减肥套餐的餐厅。这些餐厅之所以能在金融危机的影响下,保持较好的业绩,就是因为他们的主管经营有道,知道如何突出店中的特色,迎合顾客的需要。可见,没有特色的,大众化的东西,会经不住时间的考验,最终会泯灭得无声无息;只有有特色的、有独到之处的东西,才能慢慢走近人们的视野,才能被人们欣赏和接受,才能获得成功。 ⑤其实,中国的崛起又何尝不是如此呢?从新中国成立到改革开放至今的半个多世纪以来,中国几届领导人坚持走有中国特色的社会主义道路,一步一个脚印,实现了复兴之梦,使中

compare 的两个重要词组区别

compare to 和compare with 的区别是什么 Compare to 是“把……比作”的意思。例如: We compare him to a little tiger. 我们把他比作小老虎。 The last days before liberation are often compared to the darkness before the dawn. 将要解放的那些日子常常被比作黎明前的黑暗。 Compare ... with 是“把……和……比较”的意思。例如: We must compare the present with the past. 我们要把现在和过去比较一下。 We compared the translation with the original. 我们把译文和原文比较了下。 从上面比较可以看出,compare with 侧重一个仔细的比较过程。有时,两者都可以互相代替。例如: He compared London to (with) Paris. 他把伦敦比作巴黎。 London is large, compared to (with) Paris. 同巴黎比较而言,伦敦大些。 在表示“比不上”、“不能比”的意思时,用compare with 和compare to 都可以。例如: My spoken English can't be compared with yours. 我的口语比不上你的。 The pen is not compared to that one. 这笔比不上那支。 1、c ompare…to…意为“把…比作”,即把两件事物相比较的同时,发现某些方面相似的地方。这两件被比较的事物 或人在本质方面往往是截然不同的事物。如: He compared the girl to the moon in the poem. 他在诗中把那姑娘比作月亮。 2、compare…with…“与…相比,把两件事情相比较,从中找出异同”,这两件事又往往是同类的, 如:I'm afraid my English compares poorly with hers. 恐怕我的英语同她的英语相比要差得多。 compare to和compare with有何区别,当说打比方时和做比较是分别用哪个? compare…to…比喻.例如: The poets often compare life to a river. 诗人们经常把生活比喻成长河. compare…with…相比.例如: My English can't compare with his. 我的英文水平不如他.

五种计算机语言的特点与区别

php语言,PHP(PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor的缩写,中文名:“PHP:超文本预处理器”)是一种通用开源脚本语言。语法吸收了C语言、Java和Perl的特点,入门门槛较低,易于学习,使用广泛,主要适用于Web开发领域。 特性:PHP 独特的语法混合了C、Java、Perl 以及PHP 自创新的语法;PHP可以比CGI 或者Perl更快速的执行动态网页——动态页面方面,与其他的编程语言相比,PHP是将程序嵌入到HTML文档中去执行,执行效率比完全生成htmL标记的CGI要高许多,PHP具有非常强大的功能,所有的CGI的功能PHP都能实现;PHP支持几乎所有流行的数据库以及操作系统;最重要的是PHP可以用C、C++进行程序的扩展。 Java语言,Java是一种可以撰写跨平台应用软件的面向对象的程序设计语言,是由Sun Microsystems公司于1995年5月推出的Java程序设计语言和Java平台(即JavaSE, JavaEE, JavaME)的总称。 Java 技术具有卓越的通用性、高效性、平台移植性和安全性,广泛应用于个人PC、数据中心、游戏控制台、科学超级计算机、移动电话和互联网,同时拥有全球最大的开发者专业社群。在全球云计算和移动互联网的产业环境下,Java更具备了显著优势和广阔前景。 Java的优势,与传统程序不同,Sun 公司在推出Java 之际就将其作为一种开放的技术。全球数以万计的Java 开发公司被要求所设计的Java软件必须相互兼容。“Java 语言靠群体的力量而非公司的力量”是Sun公司的口号之一,并获得了广大软件开发商的认同。这与微软公司所倡导的注重精英和封闭式的模式完全不同。 Sun 公司对Java 编程语言的解释是:Java 编程语言是个简单、面向对象、分布式、解释性、健壮、安全与系统无关、可移植、高性能、多线程和动态的语言。 python语言,是一种面向对象、直译式计算机程序设计语言,Python语法简洁而清晰,具有丰富和强大的类库。它常被昵称为胶水语言,它能够很轻松的把用其他语言制作的各种模块(尤其是C/C++)轻松地联结在一起。 常见的一种应用情形是,使用python快速生成程序的原型(有时甚至是程序的最终界面),然后对其中有特别要求的部分,用更合适的语言改写。 Python是完全面向对象的语言。函数、模块、数字、字符串都是对象。并且完全支持继承、重载、派生、多继承,有益于增强源代码的复用性。 Python支持重载运算符和动态类型。相对于Lisp这种传统的函数式编程语言,Python对函数式设计只提供了有限的支持。有两个标准库(functools, itertools)提供了Haskell和Standard

“的、地、得”的用法和区别

“的、地、得”的用法和区别 一、“的、地、得”的基本概念 1、“的、地、得”的相同之处。 “的、地、得”是现代汉语中高频度使用的三个结构助词,都起着连接作用;它们在普通话中都读轻声“de”,没有语音上的区别。 2、“的、地、得”的不同之处。 吕叔湘、朱德熙所著《语法修辞讲话》认为“的”兼职过多,负担过重,而力主“的、地、得”严格分工。50 年代以来的诸多现代汉语论著和教材,一般也持这一主张。从书面语中的使用情况看,“的”与“地”、“得”的分工日趋明确,特别是在逻辑性很强的论述性、说明性语言中,如法律条款、学术论著、外文译著、教科书等,更是将“的”与“地”、“得”分用。 “的、地、得”在普通话里都读轻声“de”,但在书面语中有必要写成三个不同的字:在定语后面写作“的”,在状语后面写作“地”,在补语前写作“得”。这样做的好处,就是可使书面语言精确化。 二、“的、地、得”的用法 (一)、用法 1、的——定语的标记,一般用在主语和宾语的前面。“的”前面的词语一般用来修饰、限制“的”后面的事物,说明“的”后面的事物怎么样。 结构形式一般为:形容词、名词(代词)+的+名词。如: ①颐和园(名词)的湖光山色(主语)美不胜收。 ②她是一位性格开朗的女子(名词,宾语)。 2、地——状语的标记,一般用在谓语(动词、形容词)前面。“地”前面的词语一般用来形容“地”后面的动作,说明“地”后面的动作怎么样。 结构方式一般为:形容词(副词)+地+动词(形容词)。如: ③她愉快(形容词)地接受(动词,谓语)了这件礼物。 ④天渐渐(时间副词)地冷(形容词,谓语)起来。 3、得——补语的标记,一般用在谓语后面。“得”后面的词语一般用来补充说明“得”前面的动作怎么样。 结构形式一般为:动词(形容词)+得+副词。如: ⑤他们玩(动词,谓语)得真痛快(补语)。 ⑥她红(形容词,谓语)得发紫(补语)。 (二)、例说 的,一般用在名词和形容词的后面,用在描述或限制人物、事物时,形容的词语与被形容的词语之间,表示一种描述的结果。如:“漂亮的衣服”、“辽阔的土地”、“高大的山脉”。结构一般为名词(代词或形容词)+的+名词。如,我的书、你的衣服、他的孩子,美丽的景色、动听的歌曲、灿烂的笑容。 地,用法简单些,用在描述或限制一种运动性质、状态时,形容的词语与被形容的词语之间。结构通常是形容词+地+动词。前面的词语一般用来形容后面的动作。一般“地”的后面只跟动词。比如高兴地跳、兴奋地叫喊、温和地说、“飞快地跑”;“匆匆地离开”;“慢慢地移动”......... 得,用在说明动作的情况或结果的程度时,说明的词语与被说明的词语之间,后面的词语一般用来补充和说明前面的情况。比如。跑得飞快、跳得很高、显得高雅、显得很壮、馋得直流口水、跑得快、飞得高、走得慢、红得很……得通常用在动词和形容词(动词之间)。结构为动词(或形容词)+得+形容词(动词或副词)。

同步电机与异步电机区别说的非常好修订稿

同步电机与异步电机区别说的非常好 公司标准化编码 [QQX96QT-XQQB89Q8-NQQJ6Q8-MQM9N]

一、同步电机和异步电机在设计上的不同: ①同步与异步的最大区别就在于看他门的转子速度是不是与定子旋转的磁场速度一致,如果转子的旋转速度与定子是一样的,那就叫同步电动机,如果不一致,就叫异步电动机。。。 ②当极对数一定时,电机的转速和频率之间有严格的关系,用电机专业术语说,就是同步。异步电机也叫感应电机,主要作为电动机使用,其工作时的转子转速总是小于同步电机。 ③所谓“同步”就是电枢(定子)绕组流过电流后,将在气隙中形成一旋转磁场,而该磁场的旋转方向及旋转速度均与转子转向,转速相同,故为同步。 异步电机的话,其旋转磁场与转子存在相对转速,即产生转距。 二、为什么会同步,为什么会不同步呢? 同步电机和异步电机的定子绕组是相同的,主要区别在于转子的结构。同步电机的转子上有直流励磁绕组,所以需要外加励磁电源,通过滑环引入电流;而异步电机的转子是短路的绕组,靠电磁感应产生电流。相比之下,同步电机较复杂,造价高。 同步和异步电机均属交流动力电机,是靠50Hz交流电网供电而转动。异步电机是定子送入交流电,产生旋转磁场,而转子受感应而产生磁场,这样两磁场作用,使得转子跟着定子的旋转磁场而转动。其中转子比定子旋转磁场慢,有个转差,不同步所以称为异步机。而同步电机定子与异步电机相同,但其转子是人为加入直流电形成不变磁场,这样转子就跟着定子旋转磁场一起转而同步,始称同步电机。 简单的说就是:异步电机的转子上没加直流励磁电流,同步电机的转子上加了一个直流励磁电流使转子的转速与定子与转子切割产生的磁场转速一致。 三、同步发电机转子为什么要通入直流励磁电流,而不通入交流励磁电流? 按工频50HZ考虑,转子通入直流励磁电流,可在定子绕组中感应出50HZ电势。 转子通入交流励磁电流后,可分解为正向与反向两个旋转磁场,正向旋转磁场旋转速度与转子旋转速度迭加,在定子绕组中感应出100HZ电势;反向旋转磁

战略与策略的主要区别

战略与策略的主要区别 一,什么是战略营销? 必须首先明确,什么是战略。 1,战略的本质是一个企业的选择。为什么要做选择?因为任何一个企业都不是全能的。不可能做所有的事情,也不是所有的事情都能做好!任何企业的资源和能力都是有限的。战略就是要把有限的资源和能力,用到产出最大的地方。战略就是一个选择的过程,选择什么?如何选择?这是企业战略规划所要研究的课题。 2,战略首先意味着放弃。在中国目前的经济环境下,战略对于企业家的意义,更为重要的是“放弃”。中国的经济处在快速发展期,有太多的市场机会可供选择。但选择意味着放弃,而放弃是一件很痛苦的事情。 综上所述,战略选择的核心是对企业目标客户群的选择。而战略营销就是从战略的高度思考和规划企业的营销过程,是聚焦最有价值客户群的营销模式。 我们都知道80/20原理,20%的客户创造了企业80%的利润。战略营销要做的就是找到适合企业的目标客户群,并锁定他们进行精确打击,使企业的资源和能力发挥最大的效益,并实现企业能力的持续提升。 因此,战略营销的三个关键要素就是:1)客户细分;2)聚焦客户价值;3)为股东和客户增值。 二,什么是策略营销? 策略营销主要指的是在市场营销中,将企业的市场策略运用到营销中的过程。 比如: 1,低成本策略 通过降低产品生产和销售成本,在保证产品和服务质量的前提下,使自己的产品价格低于竞争对手的价格,以迅速扩大的销售量提高市场占有率的竞争策略。 2.差别化策略 通过发展企业别具一格的营销活动,争取在产品或服务等方面具有独特性,使消费者产生兴趣而消除价格的可比性,以差异优势产生竞争力的竞争策略。 3.聚焦策略 通过集中企业力量为某一个或几个细分市场提供有效的服务,充分满足一部分消费者的特殊需求,以争取局部竞争优势的竞争策略。 一个企业的市场营销策略必须是在企业的战略营销策略下确定的,可以简单把策略营销理解成企业在市场的战术营销。这就是两者的区别!

真理的定义和特点以及谬误的区别

、真理的定义和特点以及谬误的区别 定义:真理是人们对客观事物及其规律的正确反映。 特点:1、真理具有客观性。真理的内容是客观的;检验真理的标准是客观的。 2、真理具有价值性。真理的价值性是指真理对人类实践活动的功能性,它揭示了客观真理具有能满足主体需要、对主体有用的属性。 9.资本循环和资本周转(资本循环的三个阶段三大职能,两大前提条件;资本周转的定义,影响周转的因素) 资本循环指产品资本从一定的形式出发,经过一系列形式的变化,又回到原来出发点的运动。产品资本在循环过程中要经历三个不同的阶段,于此相联系的是资本依次执行三种不同的职能: 第一个阶段是购买阶段,即生产资料与劳动力的购买阶段。它属于商品的流通过程,在这一阶段,产业资本执行的是货币资本的职能。 第二个阶段是生产阶段,即生产资料与劳动者相结合生产物质财富并使生产资本得以增值,执行的是生产资本的职能。 第三个阶段是售卖阶段,即商品资本向货币资本的转化阶段。在此阶段产业资本所执行的是商品资本的职能,通过商品买卖实现商品的价值,满足人们的需要。 资本循环必须具备两个基本前提条件: 一是产业资本的三种职能形式必须在空间上同时并存,也就是说,产业资本必须按照一定比例同时并存于货币资本、生产资本和商品资本三种形式中。 二是产业资本的三种职能形式必须在时间上继起,也就是说,产业资本循环的三种职能形式必须保持时间上的依次连续性。 资本周转是资本反复不断的循环运动所形成的周期性运动。 影响资本周转最重要的两个要素是:一是资本周转的时间;二是生产资本的固定资本和流动资本的构成。要加快资本周转的时间,获得更多的剩余价值,就要缩短资本周转时间,加快流动资本周转速度。 第五章 2.垄断条件下竞争的特点 竞争目的上,垄断竞争是获取高额利润,并不断巩固和扩大自己的垄断地位和统治权力;竞争手段上,垄断组织的竞争,除采取各种形式的经济手段外,还采取非经济手段,使经济变得更加复杂、更加激烈; 在竞争范围上,国际市场的竞争越来越激烈,不仅经济领域的竞争多种多样,而且还扩大到经济领域范围以外进行竞争。 总之,垄断条件下的竞争,不仅规模大、时间长、手段残酷、程度更加激烈,而且具有更大的破坏性。 3.金融寡头如何握有话语权 金融寡头在经济领域中的统治主要通过“参与制”实现。所谓参与制,即金融寡头通过掌握

的、地、得的用法和区别

“的、地、得”的用法和区别 导入(进入美妙的世界啦~) “的、地、得”口诀儿歌 的地得,不一样,用法分别记心上, 左边白,右边勺,名词跟在后面跑。 美丽的花儿绽笑脸,青青的草儿弯下腰, 清清的河水向东流,蓝蓝的天上白云飘, 暖暖的风儿轻轻吹,绿绿的树叶把头摇, 小小的鱼儿水中游,红红的太阳当空照, 左边土,右边也,地字站在动词前, 认真地做操不马虎,专心地上课不大意, 大声地朗读不害羞,从容地走路不着急, 痛快地玩耍来放松,用心地思考解难题, 勤奋地学习要积极,辛勤地劳动花力气, 左边两人双人得,形容词前要用得, 兔子兔子跑得快,乌龟乌龟爬得慢, 青青竹子长得快,参天大树长得慢, 清晨锻炼起得早,加班加点睡得晚, 欢乐时光过得快,考试题目出得难。 知识典例(注意咯,下面可是黄金部分!) 的、地、得 “的”、“地”、“得”的用法区别本是中小学语文教学中最基本的常识,但在使用中也最容易发生混淆,再加上一段时间里,中学课本中曾将这三个词的用法统一为“的”,因此造成了很多人对它们的用法含混不清进而乱用一通的现象。

一、“的、地、得”的基本概念 1、“的、地、得”的相同之处。 “的、地、得”是现代汉语中高频度使用的三个结构助词,都起着连接作用;它们在普通话中都读轻声“de”,没有语音上的区别。 2、“的、地、得”的不同之处。 吕叔湘、朱德熙所著《语法修辞讲话》认为“的”兼职过多,负担过重,而力主“的、地、得”严格分工。50 年代以来的诸多现代汉语论著和教材,一般也持这一主张。从书面语中的使用情况看,“的”与“地”、“得”的分工日趋明确,特别是在逻辑性很强的论述性、说明性语言中,如法律条款、学术论著、外文译著、教科书等,更是将“的”与“地”、“得”分用。 “的、地、得”在普通话里都读轻声“de”,但在书面语中有必要写成三个不同的字:在定语后面写作“的”,在状语后面写作“地”,在补语前写作“得”。这样做的好处,就是可使书面语言精确化。 二、“的、地、得”的用法 1、的——定语的标记,一般用在主语和宾语的前面。“的”前面的词语一般用来修饰、限制“的”后面的事物,说明“的”后面的事物怎么样。结构形式一般为:形容词、名词(代词)+的+名词。如: ①颐和园(名词)的湖光山色(主语)美不胜收。 ②她是一位性格开朗的女子(名词,宾语)。 2、地——状语的标记,一般用在谓语(动词、形容词)前面。“地”前面的词语一般用来形容“地”后面的动作,说明“地”后面的动作怎么样。结构方式一般为:形容词(副词)+地+动词(形容词)。如: ③她愉快(形容词)地接受(动词,谓语)了这件礼物。 ④天渐渐(时间副词)地冷(形容词,谓语)起来。 3、得——补语的标记,一般用在谓语后面。“得”后面的词语一般用来补充说明“得”前面的动作怎么样,结构形式一般为:动词(形容词)+得+副词。如: ⑤他们玩(动词,谓语)得真痛快(补语)。

演讲稿和发言稿的区别 论坛演讲稿 精品

演讲稿和发言稿的区别论坛演讲稿 内容包括三个方面: 一新课程总目标与基本理念. 二、教材特点与竞业园单元整体问题导学模式. 三、挖掘教材——对教材使用的几点建议.首先是课程总目标与基本理念. 新《课标》明确指出:基础教育阶段英语课程的任务是: 1、激发和培养学生学习英语的兴趣,使学生树立自信心(confidence),养成良好的学习习惯和形成有效的学习策略(goodLanguageLearningStrategy),发展自己学习的能力和合作精神(theabilityofself-studyandthespiritofcooperation). 2、使学生掌握一定的英语基础知识和听(Listening)、说(Speaking)、读(Reading)、写(Writing)技能,形成一定的综合语言运用能力(Fourskills). 3.培养学生的观察、记忆、思维、想像能力和创新精神. 4、帮助学生了解世界和中西方文化差异,拓展视野,培养爱国主义精神,形成健康的人生,为他们的终身学习和发展打下了良好的基础.可以看到,课程总目标与我们教学的三维目标是相一致的,就英语学科来说,知识目标包括语音、词汇和语法. 能力目标侧重英语作为一种工具在学生实际生活中的运用.而情感目标则是希望学生能在情感态度价值观以及跨文化交际意识等方面都有所提高. 第二个方面的内容是英语新目标教材特点与竞业园单元整体问题导学模式.新目标英语GoForIt!改变了以往以讲为主的教学模式,融入了合作互动的信心理念,将教师的引导作用和学生的自主学习结合起来,从而达到了教学实效. 在新目标英语教学实践中,渗透合作互动理念.包括科学引导小组讨论、设置情景化的英语教学氛围,强调趣味教学等内容. GoForIt!最显著的特征就是要求学生采用自主学习、合作学习和探究式学习的学习方式.这与我们竞业园单元整体问题导学模式以及课堂小组的建设非常一致. 我们知道GoForIt!是个典型的美国词组,意思是冒一下险.但冒了一下险并不意味你就一定会成功,而不去尝试,那么你就会错过一次机会.

功能和特点的区别Excel的主要功能和特点

功能和特点的区别Excel的主要功能和特点 Excel的主要功能和特点 Excel电子表格是office系列办公软的-种,实现对日常生活、工作中的表格的数据处理。它通过友好的人机界面,方便易学的智能化操作方式,使用户轻松拥有实用美观个性十足的实时表格,是工作、生活中的得力助手。 一、Excel功能概述; 1、功能全面:几乎可以处理各种数据 2、操作方便:菜单、窗口、对话框、工具栏 3、丰富的数据处理函数 4、丰富的绘制图表功能:自动创建各种统计图表 5、丰富的自动化功能:自动更正、自动排序、自动筛选等 6、运算快速淮确: 7、方便的数据交换能力 8、新增的Web工具 二、电子数据表的特点Excel 电子数据表软工作于Windows平台,具有Windows环境软的所有优点。而在图形用户界面、表格处理、数据分析、图表制作和网络信息共享等方面具有更突出的特色。工.图形用户界面Excel 的图形用户界面是标准的Windows的窗口形式,有控制菜单、最大化、最小化按钮、标题栏、菜单栏等内容。其中的

菜单栏和工具栏使用尤为方便。菜单栏中列出了电子数据表软的众多功能,工具栏则进一步将常用命令分组,以工具按钮的形式列在菜单栏的下方。而且用户可以根据需要,重组菜单栏和工具栏。在它们之间进行复制或移动操作,向菜单栏添加工具栏按钮或是在工具栏上添加菜单命令,甚至定义用户自己专用的菜单和工具栏。当用户操作将鼠标指针停留在菜单或工具按钮时,菜单或按钮会以立体效果突出显示,并显示出有关的提示。而当用户操作为单击鼠标右键时,会根据用户指示的操作对象不同,自动弹出有关的快捷菜单,提供相应的最常用命令。为了方便用户使用工作表和建立公式,Excel 的图形用户界面还有编辑栏和工作表标签。. 2.表格处理 Excel的另-个突出的特点是采用表格方式管理数据,所有的数据、信息都以二维表格形式(工作表)管理,单元格中数据间的相互关系一目了然。从而使数据的处理和管理更直观、更方便、更易于理解。对于曰常工作中常用的表格处理操作,例如,增加行、删除列、合并单元格、表格转置等操作,在Excel中均只需询单地通过菜单或工具按钮即可完成。此外Excel还提供了数据和公式的自动填充,表格格式的自动套用,自动求和,自动计算,记忆式输入,选择列表,自动更正,拼写检查,审核,排序和筛选等众多功能,可以帮助用户快速高效地建立、编辑、编排和管理各种表格。

衬托与对比的区别

衬托与对比的区别 衬托,尤其是其中的反衬,有人往往将它与对比混为一谈,其实衬托与对比的界定与区别还是比较明显的。…… 衬托,尤其是其中的反衬,有人往往将它与对比混为一谈,其实衬托与对比的界定与区别还是比较明显的。 原国家教委副主任柳斌的《中学教学全书·语文卷》里这样论述:“对照是把两种相互对应的事物或同一事物相关的两面并联列在一起,加以比照的修辞方式,也叫对比。”“映衬是用乙事物来作甲事物的陪衬,以突出事物的修辞方式。……映衬可分正反衬两类。”可见,从修辞的角度讲,对比与衬托是不同的。黄伯荣。廖序东主编的《现代汉语》里也曾明确写道:“衬托有主次之分,陪衬事物是说明被陪衬事物的;是用来突出被陪衬事物的。对比表明是对立现象的,两种对立的事物并无主次之分,而是相互依存的。因此,不可把这两种修辞混为一谈。” 事实也确实如此。例如《纳谏与止谤》一文,把虚稀纳谏之利和止谤之害,两者并无主次之分,即写此而意亦此。而《天山景物记》一文,写天然湖的景色,“在这幽静的湖上,唯一活动的东西是天鹅,天鹅的洁白增添了湖水的明净,天鹅的叫声增添了湖面的幽静。”以天鹅的洁白衬托湖水的明净,以天鹅的叫声衬托湖面的幽静,两者显然有主次之分,即写此而意指彼。 可见,衬托,就是为了使某事物的特色更加突出,用别的东西来陪衬和对照的修辞手法。衬托,若就衬体与主体的性质与关系而言,可分为正衬与反衬这两种。 正衬,即是用一与本体事物一致的观点或景物,从正面去陪衬、烘托本体事物的格式。 例如“古人尚能”头悬梁,锥刺股“孜孜不倦的学习,你们为了共产主义的伟大理想,一定会天加专心致志,废寝忘食,刻苦攻关。(郭沫若《科学的春天》) 该例拿古人“头悬梁,锥刺股”的劲头,来衬托今天有理想的青年会更加“刻苦攻关”的钻研精神。这是“正衬”。 反衬,即是把一种与本体事物相反或对立的观点、事物从反面去陪衬烘托本体事物的格式。 例如“当你下马坐在一块岩石上吸烟体息时,虽然林外是阳光灿烂,而在这遮住了天日的密林中却闪着烟头的红火光。(碧野《天山景物记》) 该例以作者骑马进入天山原始森林能看到闪着烟头的红火光,突出森林成长茂密、林子阴暗,这是“反衬”。 常言道:“红花虽好,也要靠绿叶扶持。”这句话很能说明衬托的道理。写文章亦如此,运用衬托这一技巧,会把所描写的对象表现得更加鲜明突出。而衬托在其体运用中,主要又有两种类型。 以景衬情,即通过具体生动的景物的描写,来烘托渲染人物的感情或人物的性格。 例如: ①时候既是深冬,渐近故乡时,天气又阴晦了,冷风吹进船舱中,呜呜的响,从缝隙向外一望,苍黄的天底下,远近横着几个萧索的荒村,没有一些活气。(鲁迅《故乡》)这段文字描写了故乡荒凉、冷落、窒息的景象,衬托了“我”的悲凉心情。这里是以景衬情。 ②这女人编着席。不久,在她的身子下面就编成了一大片,她像坐在一片洁白的雪地上,也像坐在一片洁白的云彩上。她有时望望淀里,淀里也是一片银白世界。水面笼起一层薄薄透明的雾,风吹过来,带着新鲜的荷叶荷花香。(孙犁《荷花淀》) 该例通过对水生嫂编织芦席的景物描写,渲染了一种清新宁静的氛围,烘托了水生嫂勤劳纯朴、温顺善良的形象,这里是以景衬人。

关于申请和请示的区别说明

关于申请和请示的区别说明 以下是关于申请和请示的区别说明,能够有助于大家对两者之间的理解。 申请和请示是两种不同的行文用法:申请:是向上级或有关部门申述理由,请求批准。请示:是下级向上级请求指示。 一、申请 申请的目的是通过向上级或有关主管部门提出自己明确而具体的某种要求并申明理由,以期得到批准。申请的一般格式是: 1、标题包括事由和文件名称,如"申请购买××物资"。 2、正文包括申请原因(含申请者有关方面的基本状况)、事项、理由和要求。 3、结尾署明申请者和日期。写申请书,事项要明确,态度要积极,言辞要恳切,理由要充分。 二、请示 请示属上行文。请示的作用在于请示工作要求上级批复。请示产生于事前,不可"先斩后奏",这是请示区别于报告的主要特征之一。请示由标题、主送单位、正文、发文机关、日期构成。 1、标题一般由请示单位、请示事由、文种或请示事由和文种组成。 2、正文正文一般由三个部分组成: ①请示缘由:提出请示的原因和理由。 ②请示事项:提出有关问题要求上级指示或批准,有的要求提出

解决问题的建议和意见,供上级机关参考。提出的请示,要符合有关方针、政策,切实可行,不可矛盾上交。 ③请示要求:应明确提出要求解决问题的方法或途径,常用"是否妥当,请批示"、"妥否,请批示"、"如无不妥,请批转有关单位执行"等等。 三、请示与申请的区别: 1、申请是因业务或事务需要,按规定完成法律程序向上级或职能部门、管理机构、组织、社团说明理由,提出请求,希望得到批准的一种事务文书,也叫申请书或申请表。请示和申请都有请求原由、请求事项,但请示是法定公文,申请为专用书信,属于不同文种。 2、请示用于下级机关向上级提出请求,下级只能在上级机关的职权范围内报请需要批准的事项。申请不仅用于下级向上级请求,不属于请求范围之内的事项,而且可用于不相录属的但按规定、法律程序必须向其请求的机关、单位、部门等。如专门办理有关业务的机构部门(银行、保险、公安、海关、土地管理、工商管理等)。 3、请示的行文对象固定,而申请的行文对象不定,请示的内容限于本系统,本部门的行政公务或政策问题,写法规范。申请的内容不以系统、部门为限,写法不强求一律,且常以填写有关部门印制的各种表格代替。 4、请示的作者是法定的机关、团体,而申请的作者可以是机关、团体,也可以是个人。机关、团体或个人向有关方面递交申请,有时必须按有关规定出具或提交有关证明、证件、文件等,而请示则没有

论古今字和通假字的异同

论古今字和通假字的异同 古今字与通假字都是古书中的用字方法,要了解它们之间的相同点与不同点,首先必须从二者的概念出发。古今字——指古今同词异形而又有区别意义的一组字。古字先出,今字是为承担古字的某一部分意义而早的字。通假字是指“与…本字?相对,本有其字的同音替代字(同音也包括音近在内)。由上述二者的概念可以看出,他们具有一个很明显的相同点——二者都有字的相互对应关系.其中古今字是古字与今字的对应关系,通假字是本字与(借字)之间的关系。那么怎样辨别两个字之间是古字与今字的关系还是本字与借字之的关系?这主要就要从 二者之间的区别来看了。 (一)时间差别 古今字,顾名思义,是古字与今字的对应,所以有明显的时间先后顺序,古字总是在今字之前产生的。但是,这种先后顺序是相对的,清代段玉裁所说的“古今无定时,周为古则汉为今,汉为古则晋宋为今,随时异用者谓之古今字”就很好的揭示了这种时间的相对性。《诗经.风雨》里“胡瞻尔庭有县貆兮”一句中的“县”字就是古今字一个很好的代表。《说文解字》中说:“县,系也”。徐铉注:“此本县挂之县,借为州县之县,今俗加心别作悬义。”由此可知“县”比“悬”产生得早,也就是说“悬”是“县”的今字。另外看《诗经.七月》里“四之日其蚤”一句,在此句中,“蚤”是通“早”,指“早朝,是一种祭祀仪式”。在《左传.隐公元年》中有“不如早为之所”句,而《论衡.问孔》中又有“颜渊蚤

死”句,《论衡》成书在《左传》、后,可见“蚤”字通行的同时,“早”已存在。所以它们之间不是古今字的关系,而是通假字的关系。 (二)关系的差别 古今字的古字与今字之间的相互关系有两种情况:(1)一个古字与一个今字相对。如“女”与“汝”相对。“女”有“女子、女儿”的意思,但它又假借为第二人称代词,后来另造“汝”代替,如《左传.齐桓公伐楚》中“女实征之”里的“女”。(2)一个古字与多个今字相对。如古字“采”与“彩”、“綵”、“採”的对应关系。“采”的本意是“采摘”,参差荇菜,左右采之”里的“采”即为本意。但在”抑为采色不足视于目与?”中“采”则假借为“彩色”之意,后改写为“彩”。“采”又有“彩绸”的意思,《汉书》:“文采千匹”中的“采”后来就写成“綵”。为了区别,后人又造了一个“採”字来表示“采摘”这个本意。这样,“采”与“彩”,“采”与“綵”,“采”与“採”就形成了三对古今字。与古今字向比较,通假字中借字与本字之间的关系则分为三种情况,除与古今字一样有一个本字对应一个借字,一个本字对应多个借字的关系外,还有多个本字与一个借字相对的情况。如:“矢”的本意为“箭”,“誓”的本意为“誓言”,又为动词“发誓”,“屎”的本意为“粪便”,在古籍中,却常常用“矢”来表示“誓”或“屎”。而古今 字是没有这种对应关系的。 (三)意义差别

各类格式的特点区分

在用各类软件设计时相信大家肯定存在着这样的问题,各种各样的格式让大家很是迷惑。没关系,福利来了,这里就给大家介绍了各种格式的特点应用。 TIFF格式 标签图像文件格式(Tagged Image File Format,简写为TIFF) 是一种主要用来存储包括照片和艺术图在内的图像的文件格式。它最初由Aldus公司与微软公司一起为PostScript 打印开发.TIFF文件格式适用于在应用程序之间和计算机平台之间的交换文件,它的出现使得图像数据交换变得简单。 TIFF是最复杂的一种位图文件格式。TIFF是基于标记的文件格式,它广泛地应用于对图像质量要求较高的图像的存储与转换。由于它的结构灵活和包容性大,它已成为图像文件格式的一种标准,绝大多数图像系统都支持这种格式。用Photoshop 编辑的TIFF文件可以保存路径和图层。 应用广泛 (1)TIFF可以描述多种类型的图像;(2)TIFF拥有一系列的压缩方案可供选择;(3)TIFF 不依赖于具体的硬件;(4)TIFF是一种可移植的文件格式。 可扩展性 在TIFF 6.0中定义了许多扩展,它们允许TIFF提供以下通用功能:(1)几种主要的压缩方法;(2)多种色彩表示方法;(3)图像质量增强;(4)特殊图像效果;(5)文档的存储和检索帮助。 格式复杂 TIFF文件的复杂性给它的应用带来了一些问题。一方面,要写一种能够识别所有不同标记的软件非常困难。另一方面,一个TIFF文件可以包含多个图像,每个图像都有自己的IFD 和一系列标记,并且采用了多种压缩算法。这样也增加了程序设计的复杂度。 文档图像中的TIFF TIFF格式是文档图像和文档管理系统中的标准格式。在这种环境中它通常使用支持黑白(也称为二值或者单色)图像的CCITT Group IV 2D压缩。在大量生产的环境中,文档通常扫描成黑白图像(而不是彩色或者灰阶图像)以节约存储空间。A4大小200dpi(每英寸点数分辨率)扫描结果平均大小是30KB,而300dpi的扫描结果是50KB。300dpi比200dpi更

“的、地、得”的用法和区别

的、地、得的用法和区别 的、地、得的用法和区别老班教育 一、的、地、得的基本概念 1、的、地、得的相同之处。 的、地、得是现代汉语中高频度使用的三个结构助词,都起着连接作用;它们在普通话中都读轻声de,没有语音上的区别。 2、的、地、得的不同之处。 吕叔湘、朱德熙所著《语法修辞讲话》认为的兼职过多,负担过重,而力主的、地、得严格分工。50 年代以来的诸多现代汉语论著和教材,一般也持这一主张。从书面语中的使用情况看,的与地、得的分工日趋明确,特别是在逻辑性很强的论述性、说明性语言中,如法律条款、学术论著、外文译著、教科书等,更是将的与地、得分用。 的、地、得在普通话里都读轻声de,但在书面语中有必要写成三个不同的字:在定语后面写作的,在状语后面写作地,在补语前写作得。这样做的好处,就是可使书面语言精确化。 二、的、地、得的用法 (一)、用法 1、的——定语的标记,一般用在主语和宾语的前面。的前面的词语一般用来修饰、限制的后面的事物,说明的后面的事物怎么样。 结构形式一般为:形容词、名词(代词)+的+名词。如: 颐和园(名词)的湖光山色(主语)美不胜收。 她是一位性格开朗的女子(名词,宾语)。 2、地——状语的标记,一般用在谓语(动词、形容词)前面。地前面的词语一般用来形容地后面的动作,说明地后面的动作怎么样。 结构方式一般为:形容词(副词)+地+动词(形容词)。如: 她愉快(形容词)地接受(动词,谓语)了这件礼物。 天渐渐(时间副词)地冷(形容词,谓语)起来。 3、得——补语的标记,一般用在谓语后面。得后面的词语一般用来补充说明得前面的动作怎么样。 结构形式一般为:动词(形容词)+得+副词。如: 他们玩(动词,谓语)得真痛快(补语)。 她红(形容词,谓语)得发紫(补语)。 (二)、例说 的,一般用在名词和形容词的后面,用在描述或限制人物、事物时,形容的词语与被形容的词语之间,表示一种描述的结果。如:漂亮的衣服、辽阔的土地、高大的山脉。结构一般为名词(代词或形容词)+的+名词。如,我的书、你的衣服、他的孩子,美丽的景色、动听的歌曲、灿烂的笑容。 地,用法简单些,用在描述或限制一种运动性质、状态时,形容的词语与被形容的词语之间。结构通常是形容词+地+动词。前面的词语一般用来形容后面的动作。一般地的后面只跟动词。比如高兴地跳、兴奋地叫喊、温和地说、飞快地跑;匆匆地离开;慢慢地移动......... 得,用在说明动作的情况或结果的程度时,说明的词语与被说明的词语之间,后面的词语一般用来补充和说明前面的情况。比如。跑得飞快、跳得很高、显得高雅、显得很壮、馋得直流口水、跑得快、飞得高、走得慢、红得很……得通常用在动词和形容词(动词之间)。

借代和比喻的区别

借代和比喻的区别 说话或写文章时不直接说出所要表达的人或事物,而是借用与它有密切相关的人或事物来代替,这种修辞方法叫借代。被替代的叫\'本体\',替代的叫\'借体\',\'本体\'不出现,用\'借体\'来代替。借代 可分为三类:旁代、对代、其它。 借代与借喻的区别是:借代的本体与借体之间有实在的关系,一般地 说,这种关系还是相当密切的; 借喻的本体与喻体是本质不同的事物,人们不过根据它们之间具有的相似点,通过联想把它们联系起来。 恰当地运用借代可以突出事物的本质特征,增强语言的形象性,而且可以使文笔简洁精炼,语言富于变化和幽默感。 借代是指一件事物換個說法,借喻則是指比方和被比方兩件事物。借代的本體和借體之間不能加「像」字,借喻的本體和喻體間可以加 「像」字。 作用:使語言簡潔、生動、形象化,喚起讀者的聯想。 例子(1):巾幗不讓鬚眉。(以「巾幗」借代女人、「鬚眉」借代男人。)例子(2):朱門酒肉臭,路有凍死骨。《自京赴奉先縣詠懷五百字》杜甫(以「朱門」借代富貴之家、「死骨」借代屍體。) 例子(3):過盡千帆皆不是。《夢江南》.其二溫庭筠(以「帆」借 代帆船。) 例子(4):黃髮、垂髫,並怡然自樂。《桃花源記》陶潛(以「黃髮」 借代老人、「垂髫」借代小孩。)

例子(5):她希望長大後當白衣天使。(以「白衣天使」借代護士。) 借喻可改为明喻或暗喻,借代不能 借代和借喻,在\'代替本体事物\'这一点上是相通的。但它们的区别 是明显的:二者构成的基础不同。借喻是比喻的一种,它成立的基础必须是本体与喻体本质不同而又有相似点的东西,它利用的是本体事物与喻体事物的\'相似性\'。借代的基础是相关性,它不直接说出要 表达的人或事物,而是借用和这个人或事物有密切关系的东西来代替。 区别借代与借喻的最简便的方法是借喻可以还原为明喻,借代则不能。借喻是一种省略了本体和比喻词的比喻,完全可以根据具体语境把本体找出来,再加一个“像”字将借喻还原成明喻的形式。比如:燕雀安知鸿鹄之志哉?“燕雀”和“鸿鹄”都是借喻,我们把它们还原成明喻形式:那些目光短浅的人好象渺小的燕雀;自己好象翱翔万 里的鸿鹄。 借代是用甲事物来代替乙事物,甲乙两事物之间的联系是有某些相关之处。记住是相关性,部分可以代替整体,特征可以代替事物。比如:那边来了个红领巾。“红领巾”是借代,是用少先队员的标志来代替少先队员。不能说少年队员象红领巾。再比如:枪杆子里面出政权。“枪杆子”是借代,用“枪杆子”来代替“武装斗争”。因为“武装斗争”必须得用枪杆子,二者之间有联系。不能说武装斗争像枪杆子。