Modelling municipal solid waste generation A review

Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214

https://www.360docs.net/doc/876938675.html,/locate/wasman

0956-053X/$ - see front matter ? 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2006.12.011

Review

Modelling municipal solid waste generation: A review

Peter Beigl, Sandra Lebersorger, Stefan Salhofer

¤

Institute of Waste Management, Department of Water, Atmosphere and Environment, BOKU – University of Natural Resources and Applied Life

Sciences, Muthgasse 107, 1190 Vienna, Austria

Accepted 27 December 2006Available online 1 March 2007

Abstract

The objective of this paper is to review previously published models of municipal solid waste generation and to propose an implemen-tation guideline which will provide a compromise between information gain and cost-e Y cient model development. The 45 modelling approaches identi W ed in a systematic literature review aim at explaining or estimating the present or future waste generation using eco-nomic, socio-demographic or management-orientated data. A classi W cation was developed in order to categorise these highly heteroge-neous models according to the following criteria – the regional scale, the modelled waste streams, the hypothesised independent variables and the modelling method. A procedural practice guideline was derived from a discussion of the underlying models in order to propose bene W cial design options concerning regional sampling (i.e., number and size of observed areas), waste stream de W nition and investigation,selection of independent variables and model validation procedures. The practical application of the W ndings was demonstrated with two case studies performed on di V erent regional scales, i.e., on a household and on a city level. The W ndings of this review are W nally summa-rised in the form of a relevance tree for methodology selection.? 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Waste management for municipal waste is considered a public service, providing citizens with a system of disposing of their waste in an environmentally sound and economi-cally feasible way. The amount and composition of waste generated comprise the basic information needed for the planning, operation and optimisation of waste manage-ment systems. The demand for reliable data concerning waste arising (waste generation) is implicitly included in the majority of national waste management laws. More explic-itly, waste legislation requires assessment of the current waste arising and forecasts, such as in Ireland (Dennison et al., 1996a ) and in Germany, where the competent public authorities (cities or counties (“Kreise”)) are required to assure “guaranteed disposal” for a period of 10 years in advance (cf. Sircar et al., 2003).

This entails a demand for reliable information on waste quantity and composition, which is di Y cult to achieve on a disaggregated level. Other than in more centralised infra-structures like electricity supply (where the consumption of each single end-user can be measured), waste generation can not be measured directly. Typically, in waste disposal systems there are several parallel disposal channels (e.g.,public curbside collection; civic amenity sites for green waste, bulky waste, etc.; private collectors of, e.g., clothing textiles; take back by retailers). The waste arising on a sin-gle household basis is measured only in rare situations, e.g.,in areas where Pay-As-You-Throw systems have been installed. Thus waste generation cannot be measured on a detailed basis, which would allow further evaluation of dis-posal habits, changes and trends. In this case modelling is of particular importance.

Models and data from models are used in the planning of waste management systems, including:

–the development of waste-management strategies (Dask-alopoulos et al., 1998);

*

Corresponding author. Tel.: +43 1 3189900 319; fax: +43 1 3189900350.

E-mail address: stefan.salhofer@boku.ac.at (S. Salhofer).

P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214201

–the planning of waste collection services (Grossman

et al., 1974) and infrastructures (Dennison et al., 1996a)

or treatment facilities and capacities (e.g., the capacity evaluation of MSW incinerators by Chang and Lin,

1997); and

–land demand for facilities, especially in the context of

land W lling waste (Leao et al., 2001).

For the operation of waste management systems, waste

generation related planning data have an essential in X uence

on:

–personnel and truck utilisation (Matsuto and Tanaka,

1993), as well as operational costs (Grossman et al.,

1974) with respect to collection and transportation; and –monitoring of systems (e.g., assessing e V ects of waste

prevention action, recycling activities, etc. (cf. OECD,

2004)).

They serve as a basis for further improvements and opti-

misation in terms of sustainability (environmental, eco-

nomic and societal) targets.

The objective of this paper is to review previously pub-lished models of municipal solid waste (MSW) generation

and to propose an implementation guideline which will

provide a compromise between information gain and cost-

e Y cient model development. Models that focus on the esti-mation, explanation or prediction o

f the whole, or parts of

the MSW stream were reviewed. These streams can be de W-

ned either according to composition of MSW (regardless of

where collected) or to means of collection (separate or com-mingled). Numerous, mainly statistically based modelling

approaches have been published in the literature since 1974,

with more than 50 papers addressing the broader W eld of

this topic published through the end of 2005. In this paper, the classi W cation of these models is described in Section 2,

in order to structure the highly heterogeneous approaches.

Focussing on crucial design options within the modelling

procedure, Section 3 discusses the bene W ts and shortcom-ings of the models. Derived recommendations are summa-

rised in a comprehensive guideline. These W ndings

concerning relevant requirements for waste generation

modelling are then demonstrated with two case studies in a more detailed way focussing on model applications at

di V erent regional scales in Section 4. The conclusions of this

review are given in Section 5, including a relevance tree for

methodology selection.

2. Classi W cation of waste generation models

To date, policies promoting greater sustainability in

waste management have not been followed by equal e V orts

to boost adequate knowledge about waste generation.

Climbing up the waste management hierarchy from land-W lling, energy recovery, and material recycling up to waste minimisation will lead to increasing data complexity, thus

requiring more detailed information on waste generation and composition (Par W tt and Flowerdew, 1997). In spite of the fact that decision-support orientated waste manage-ment models, such as cost bene W t analyses, life cycle analy-ses and multicriteria decision analyses, have been established over the last decades (Morrissey and Browne, 2004), waste generation models, which deal with the under-lying, indispensable planning fundamentals, are lagging behind and are far from reaching general modelling stan-dards. Due to the multitude of possible research design options, a high heterogeneity of models – from purely application-oriented up to highly sophisticated tools – is available.

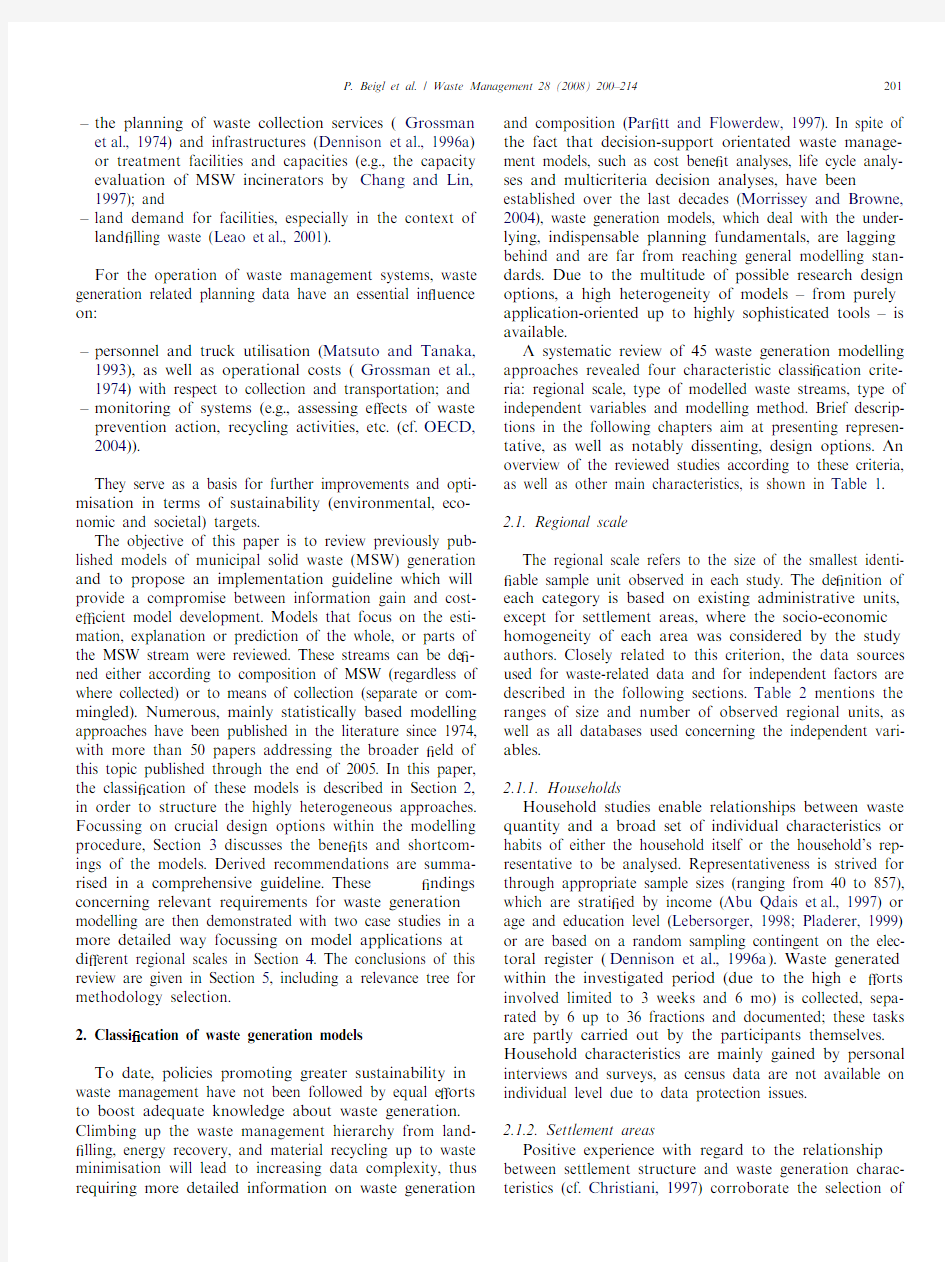

A systematic review of 45 waste generation modelling approaches revealed four characteristic classi W cation crite-ria: regional scale, type of modelled waste streams, type of independent variables and modelling method. Brief descrip-tions in the following chapters aim at presenting represen-tative, as well as notably dissenting, design options. An overview of the reviewed studies according to these criteria, as well as other main characteristics, is shown in Table 1.

2.1. Regional scale

The regional scale refers to the size of the smallest identi-W able sample unit observed in each study. The de W nition of each category is based on existing administrative units, except for settlement areas, where the socio-economic homogeneity of each area was considered by the study authors. Closely related to this criterion, the data sources used for waste-related data and for independent factors are described in the following sections. Table 2 mentions the ranges of size and number of observed regional units, as well as all databases used concerning the independent vari-ables.

2.1.1. Households

Household studies enable relationships between waste quantity and a broad set of individual characteristics or habits of either the household itself or the household’s rep-resentative to be analysed. Representativeness is strived for through appropriate sample sizes (ranging from 40 to 857), which are strati W ed by income (Abu Qdais et al., 1997) or age and education level (Lebersorger, 1998; Pladerer, 1999) or are based on a random sampling contingent on the elec-toral register (Dennison et al., 1996a). Waste generated within the investigated period (due to the high e V orts involved limited to 3 weeks and 6 mo) is collected, sepa-rated by 6 up to 36 fractions and documented; these tasks are partly carried out by the participants themselves. Household characteristics are mainly gained by personal interviews and surveys, as census data are not available on individual level due to data protection issues.

2.1.2. Settlement areas

Positive experience with regard to the relationship between settlement structure and waste generation charac-teristics (cf. Christiani, 1997) corroborate the selection of

202

P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214

homogeneous settlement areas as the sample unit. Homoge-neity of settlement density and dwelling types in a given area is assumed to implicitly control variables such as income, employment status and household size. The selected areas often correspond to the smallest administra-tive units, e.g., census blocks with several hundred inhabit-ants (Grossman et al., 1974; Lebersorger, 2004) or enumeration districts with approximately 400–600 house-holds (Par W tt and Flowerdew, 1997). An exception with much larger areas, housing approximately 80,000 inhabit-ants per area, was described by Emery et al. (2003). House-hold waste analyses typically cover the documentation of collected waste quantities and sorting analyses of samples from selected collection rounds or containers. Data sources for independent variables cover census data from statistical o Y ces, market-research based geo-demographic classi W ca-tion packages (e.g., ACORN (cf. Par W tt and Flowerdew,1997)) and questionnaire surveys.

Table 1

Characteristics of the reviewed models n.c. – no comment.

HH – Households; DI – Districts; SA – Settlement area; CO – Country.

HWF – Household waste fractions; CS – Collection streams; MS – Material streams.

C – Consumption-related;

D – Disposal-related; P – Production and trade-related variables; GC – Group comparison; CA – Correlation analysis;MR – Multiple regression analysis; SR – Single regression analysis; IOA – Input–output analysis; TSA – Time-series analysis; SD – System dynamics.a

Sorting campaigns in 37 regions.

Reference

Regions Time series length Waste streams Independent variables type Modelling method Type Units Datasets Interval Type Number Abu Qdais et al. (1997)HH 4021d HWF 6C GC, CA Bach et al. (2003)DI 1071––CS 5C, D MR Bach et al. (2004)DI 649––CS 1C, D MR Becker (1999)SA 6––CS

2C GC

Beigl et al. (2004)DI 55622y CS, HWF 6C, D MR, SR Beigl et al. (2005)

DI 2728y CS 1C SR Bogner and Matthews (2003)CO 314–7y CS 1C SR Bogner et al. (1993)

CO 13––CS 1P, C SR Brahms and Schwitters (1985)CO 1––MS 20P, C IOA Chang and Lin (1997)DI 1260m CS 1D TSA Chen and Chang (2000)DI 114y CS 1–TSA Christiani (1997)

SA 33––HWF 29C, D GC, SR Christiansen and Fischer (1999)CO 14614y MS, CS 3P, C TSA Daskalopoulos et al. (1998)CO 224y MS 6C SR

Dennison et al. (1996a,b)HH 857––HWF 36C, D GC, CA Dyson and Chang (2005)DI 4310y CS 1C SD Eder (1983)

DI 26011 6 w HWF 14C, D GC, SR Emery et al. (2003)

SA 33w HWF 30C, D GC European Commission (2002)SA n.c.a n.c.n.c.HWF n.c.C, D GC Franklin Associates (1999)CO 139y MS 10P, C IOA Gay et al. (1993)

DI 1––MS 5P, C IOA Grossman et al. (1974)SA 103––CS 1C MR Hekkert et al. (2000)CO 1––MS 62P

IOA Hockett et al. (1995)DI 100–

–CS 1P, C, D MR Jenkins (1993)

DI 96108m CS 2P, C, D MR Joosten et al. (2000)CO 1––MS 15P IOA Karavezyris et al. (2002)DI 1n.c.n.c.CS 3D SD Katsamaki et al. (1998)DI 1260d CS 1C TSA Leao et al. (2001)DI 1n.c.n.c.CS 1C TSA Lebersorger (1998)HH 50626w CS 7C GC, SR Lebersorger (2004)

SA 6––HWF 10C, D GC Martens and Thomas (1996)DI 444y CS 2C, D GC, SR Matsuto and Tanaka (1993)DI 1365d CS 2C TSA McBean and Fortin (1993)DI n.c.14y CS 2C GC, SR Navarro-Esbrí et al. (2002)DI 36730m/d CS 1C TSA OECD (2004)

CO 1655y CS 1C TSA Par W tt and Flowerdew (1997)SA 31––HWF 11C GC Par W tt et al. (2001)DI 375––CS 3D GC Patel et al. (1998)CO 1––MS n.c.P IOA Pladerer (1999)

HH 50626w CS 7C GC, SR Rhyner and Green (1988)DI 14y CS 1C GC Ru V ord (1984)

HH n.c.––HWF n.c.C, D GC Salhofer and Graggaber (1999)DI 118––CS

1C, D MR Skovgaard et al. (2005)CO 629618y MS, CS 4P, C TSA Thogersen (1996)

CO

18

2

5y

CS

1

P

SR

P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214203

2.1.

3. Districts

Both the competence of regional planning and the ready availability of data justify the fact that the majority of the models selected districts as the smallest regional unit (cf. Hockett et al., 1995). The term ‘district’ is here de W ned as administrative unit, which may correspond to municipal-ity, county, city district or city. This research design enables the achieving of full coverage of federal states (Par W tt et al., 2001; Hockett et al., 1995; Salhofer and Graggaber, 1999) or cities (Chang and Lin, 1997). If mod-elling is not limited to only one major region (Gay et al., 1993; Karavezyris et al., 2002), analysed samples cover up to several hundreds of essentially small and medium-sized municipalities (Bach et al., 2004). Several studies have doc-umented the use of time series on an annual (Beigl et al., 2004; Chen and Chang, 2000), monthly (Chang and Lin, 1997; Jenkins, 1993) or daily (Navarro-E sbrí et al., 2002; Matsuto and Tanaka, 1993) basis. While waste quantity statistics, and in some cases also sporadically conducted sorting analyses, are used as waste data, census and eco-nomic data in addition to waste management-related information (Chang and Lin, 1997; Martens and Thomas, 1996) and expert interviews (cf. Karavezyris and Marzi, 1999; Karavezyris, 2001) are used for modelling of the independent variables.

2.1.4. Countries

Models on this highest aggregation level can be classi-W ed into three types: input–output, cross-sectional and time-series analyses. While the W rst type aims at estimating waste streams, such as plastics (Patel et al., 1998; Joosten et al., 2000), paper and wood (Hekkert et al., 2000) or all

main fractions of the MSW (Franklin Associates, 1999;

Brahms and Schwitters, 1985) in a single country, the other

two regression-based methods focus on comparisons between countries and/or in time by means of aggregated

variables, such as the gross domestic product (GDP) (Tho-

gersen, 1996; Mertins et al., 1999), private consumption

expenditures for all (OECD, 2004), de W ned product items (Daskalopoulos et al., 1998; Christiansen and Fischer,

1999; Skovgaard et al., 2005) or various other indicators as

shown in a cross-sectional comparison of 13 OECD-coun-

tries by Bogner et al. (1993). The usual data sources include nationally aggregated waste quantities on an

annual basis, census-related and economic data from sta-

tistical o Y ces, and data from industry and trade associa-

tions.

2.2. Modelled MSW waste streams

The waste streams modelled in the reviewed studies can

be classi W ed into three concepts (Fig.1):

–Material streams (Type A): This most comprehensive de W nition, addressing all wastes originating from the W nal consumer, is only achieved by means of input–out-put analyses. Due to its nature, this method is not aimed

at considering the collection procedure applied. Waste quantity records, if surveyed, are not essential for the model results and may be used only for validation (see Chapter 2.4). In some studies (Daskalopoulos et al., 1998;

Christiansen and Fischer, 1999; Skovgaard et al., 2005),

Table 2

Characteristics of waste generation models by regional scale

Regional units observed Households Settlement areas Districts Country Typical range of

residents by unit

1–71200–10,00060,000–3.5 Mio.10–270 Mio.

Number of regional

units

40–8573–1031–10711–31

Data sources for dependent variables Full sorting

analysis

Representative sorting analysis Waste quantity statistics Waste quantity

statistics

Self-documented

waste quantity

Waste quantity statistics Representative sorting analysis

Data sources for independent variables Household

interview

Census Census Census

Household

questionnaire

survey

Household questionnaire survey Branch-speci W c statistics Branch-speci W c

statistics

Waste-management related

documentations of

infrastructure and activities

Waste-management related

documentations of infrastructure and

activities

Household budget

survey

Waste-management related

documentations of infrastructure and

activities

Macroeconomic

aggregate

Product-related

literature and

statistics

204P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214

results from other input–output analyses are used as dependent variables.

–Collection streams (Type B): Predominantly, o Y cial

waste statistics are used in modelling of the total MSW

collected (e.g., Leao et al., 2001; Beigl et al., 2004; Chen and Chang, 2000; Thogersen, 1996; Par W tt et al., 2001;

Hockett et al., 1995; Bogner and Matthews, 2003) or sin-

gle collection streams, such as residual waste (Becker,

1999; Chang and Lin, 1997; Grossman et al., 1974; Jen-kins, 1993; Martens and Thomas, 1996; Dyson and

Chang, 2005), the sum of all recyclables (Par W tt et al.,

2001) or single recyclable materials, such as paper and

cardboard, glass, plastics or metals (Bach et al., 2003, 2004; Lebersorger, 1998; Pladerer, 1999). Beside the

o Y cially reported waste streams, signi W cant quantitative

interchanges to other disposal options, such as private W ring (Salhofer and Graggaber, 1999; Dennison et al., 1996a), illegal disposal (Karavezyris et al., 2002) or

informal collection (cf. Fehr et al., 2000), are addressed

by a few models.

–Fractions of household waste (Type C): Models based on sorting analyses of commingled or residual wastes, respectively, from curbside collection enable the analy-sis of its composition, taking into account a range of 6 (Abu Qdais et al., 1997) to 36 (Dennison et al., 1996a) categories.

2.3. Independent variables

Salhofer (2001) has classi W ed models for the analysis of waste generation into two categories: input–output mod-els based on the X ow of material to waste generators (input) or from waste generators (output) and factor mod-els that use factors describing the processes of waste gen-eration. While the W rst classi W cation focuses on the purely descriptive characterisation of waste streams over the stages in product life cycle (from production, over trade to consumption), the second classi W cation aims at unveiling hypothesised causal relationships between factors for the prediction of waste generation. Sircar et al. (2003) have proposed horizontal and vertical factors for the predic-tion of municipal waste quantities. Horizontal factors describe the processes of interchanges between di V erent waste types. As an example, shifts between residual waste, bulky waste, recyclables and illegally disposed waste are mainly caused by di V erent modes of separate collection and do not a V ect the total waste quantity. Vertical factors are due to changes of the total sum of all waste streams depending on demographic, economic, technical and social developments.

Many independent variables have been hypothesised and tested in order to explain the quantity of total or par-tial streams of MSW. These have partly been summarised in previous reviews by Salhofer (2001), Beigl et al. (2003), Hockett et al. (1995) and Jenkins (1993). According to the above mentioned categories, grouping is based on the focussed stages in product life cycle: production and trade-related, consumption-related, and disposal-related variables.

Data concerning production and trade contain direct or indirect information about the quantity of product and waste streams over successive processing stages, at least on the level of product groups. As mass-related data are rarely available (Joosten et al., 1999), monetary data are predomi-nantly converted into physical data by surveying, assuming or statistically estimating (e.g., waste generated per GDP

P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214205

unit as done by Thogersen (1996), Bogner et al. (1993) and Mertins et al. (1999)) the price per product unit. Gay et al. (1993) used conversion factors that were based on surveys of at least three major waste generators in each sector cate-gory of the standard-industrial-code (SIC). Joosten et al. (1999) proposed di V erent options due to data availability; the mean prices per material or product unit for each indus-try is given priority over average retail prices based on national statistics and data from market inquiries, if avail-able. In order to consider the di V erences in the use phase, product-related surveys of the ‘residence time’ (i.e., the duration of the use phase) enable the assessment of waste generated (Patel et al., 1998).

Evaluations of consumption-related variables re X ect the relationship between living conditions and waste generation patterns. Further to the well documented impacts of residen-tial population and sporadically dwelling tourists on total MSW quantity (Hockett et al., 1995; Salhofer and Grag-gaber, 1999; Bach et al., 2004), most of these variables serve as proxies for the general level of a Z uence. This is especially true for the variables related to income (Hockett et al., 1995; Jenkins, 1993; Ru V ord, 1984), tenure (i.e., tenancy) of prop-erty (Ru V ord, 1984; Dennison et al., 1996a), rental rate of property (Abu Qdais et al., 1997; Grossman et al., 1974) and the private consumption expenditures by product groups (OECD, 2004; Christiansen and Fischer, 1999; Daskalopou-los et al., 1998) for which most, but not all (cf. Jenkins, 1993), of the evaluations proved the expected positive relationship. Other signi W cant a Z uence-related proxies are represented by dwelling type (E mery et al., 2003; Par W tt and Flowerdew, 1997; Dennison et al., 1996a), employment status (Dennison et al., 1996a; Ru V ord, 1984; Bach et al., 2004), and popula-tion density and urbanisation (Martens and Thomas, 1996; Jenkins, 1993; E der, 1983), as well as development and health indicators, such as life expectancy and infant mortal-ity (Bogner et al., 1993; Beigl et al., 2004, 2005). Apart from the mentioned a Z uence-related indicators, individual char-acteristics of households – namely the household size (Denn-ison et al., 1996b; Jenkins, 1993; Ru V ord, 1984), the age structure (Jenkins, 1993; Sircar et al., 2003; Ru V ord, 1984; Beigl et al., 2004), the life-cycle stage of the household (Lebersorger, 1998; Ru V ord, 1984) or consumption habits (Dennison et al., 1996a; Lebersorger, 1998) observed by means of household interviews – proved to be signi W cant.

The third group of signi W cant variables contains dis-posal-related factors which may a V ect horizontal shifts between waste types. The employment by sectors, as well as branch-speci W c sales data, were successfully used as proxy for the percentage of commercial waste (Bach et al., 2004; Martens and Thomas, 1996; Hockett et al., 1995; Gay et al., 1993). Signi W cant impacts on the quantity of source-sepa-rated recyclables are the home heating arrangement (Denn-ison et al., 1996a; Salhofer and Graggaber, 1999), fostered recycling activities (cf. Haase, 2000), container size (Mar-tens and Thomas, 1996; E der, 1983), density of collection sites (Bach et al., 2004; Par W tt et al., 2001) and user fees (Jenkins, 1993; Hockett et al., 1995).2.4. Modelling methods

The review revealed how a wide range of modelling techniques of di V erent levels of complexity have been applied to date. Seven groups of applied methods could be identi W ed as enumerated in Table 1. Di V erences between the methodological characteristics can best be described by addressing the number of independent variables, the method of model validation and the applicability for pre-dictions.

Methods enabling the consideration of only one inde-pendent variable (i.e., bivariate analysis) cover the time series analyses, correlation and regression analyses and group comparison. A common feature of these methods is that the model validation is based on real waste data. Some of these approaches can be extended to multivari-ate models using up to W ve parameters. Par W tt et al. (2001) used W ve collection-infrastructure-related vari-ables as cluster criteria for a successive group compari-son. Skovgaard et al. (2005) applied a three-parametric time series model. A method without the use of any inde-pendent variable (except the time series data with at least three values) was proposed by a projection with a grey fuzzy dynamic model proposed by Chen and Chang (2000). In addition to time series approaches, quantita-tive predictions can also be applied by means of single regression analysis as shown by a prediction model for main material fractions of MSW by Daskalopoulos et al. (1998).

Multivariate methods, such as multiple regression anal-yses, system dynamics and input–output analyses, are far more complex due to the manifold interactions between the selected parameters. Therefore, model validation is often very di Y cult or impossible to achieve. While in the case of regression models, analyses (cf. Grossman et al., 1974; Hockett et al., 1995) have to prove that each inde-pendent variable meets the stringent requirements (i.e., independence of explanatory variables, and constant vari-ance and normality of errors) to not violate the fundamen-tal regression assumptions; comparable validation procedures (e.g., to prevent intercorrelations) have not been applied for the other two methods. Regarding input–output analyses, Joosten et al. (2000) and Hekkert et al. (2000) highlight the problem that comparisons of the results obtained with the model with externally observed waste quantities on the highest aggregation levels are ques-tionable due to the presence of di V erent aggregations or low consistency within the studies, or may even prove to be impossible because “studies on W nal consumption are almost completely lacking” e.g., for plastic materials. Brahms and Schwitters (1985) compared their input–out-put analysis for main MSW fractions with a nationwide sorting analysis in Germany on the highest aggregation level proving low estimation errors for the packaging materials metals, paper/cardboard and plastics (<4%), but considerable errors for packaging glass (39%), textiles (16%) and organic waste (36%).

206P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214

3. Discussion of design options and guideline development

Models contributing to the improved estimation of pres-ent and future waste quantities and characteristics are aimed at enabling the best possible waste management planning decisions within the given constraints. Thus, the adjustment of research design is mostly induced – either explicitly or implicitly – by W nding an appropriate trade-o V between information gain and cost-e Y ciency (cf. Gay et al., 1993; Chen and Chang, 2000). In order to enable the identi-W cation of bene W cial modelling procedures in terms of these two often contradictory goals, crucial design options con-cerning

–regional sampling,

–waste stream de W nition and investigation,

–selection of independent variables to be hypothesised, and

–model validation

are discussed below by presenting bene W ts and short-comings of the reviewed literature and summarised in a proposed procedural guideline.

3.1. Regional sampling

Both the size and the number of regions to be observed represent crucial design parameters. The selection of exces-sively large, too few or too many observed regional units may challenge the usefulness, as well as the cost-e Y ciency, of an investigation for planning issues.

With regard to the size of observed units, a consoli-dated waste strategy should be accompanied by the appropriate regional discretisation of a model. Par W tt and Flowerdew (1997) illustrate the close relationship between the focus in waste management hierarchy and the typical data requirements. While the focus on material recycling requires the “local authority monitoring of recycling schemes” in order to design material recovery facilities, the focus on the more sustainable waste minimisation and material reuse strategies should be funded on household-waste audits and surveys to enable the identi W cation of “waste-creating activities”. Based on this argumentation concerning the political appropriateness of the size unit (cf. Hockett et al., 1995), two-thirds of the reviewed mod-els (i.e., 31 out of a total of 45) focus on the scale of dis-tricts or smaller regional units. In contrast, the decision makers’ bene W t of some models, which are based on data related to countries or large regions, is often questionable. The modelling of waste potentials for the USA and for whole E urope (Daskalopoulos et al., 1998) or even the estimation of recycled, legally and illegally disposed waste quantities on the level of city with more than 3million inhabitants (Karavezyris et al., 2002) can not provide rele-vant information about the regional variation, and thus can not serve as a basis for waste management planning on a regional level.

As the sample size of inquiries, such as questionnaire surveys, interviews and accompanying sorting analyses is regarded as one of the main cost drivers (cf. Schar V, 1991), cost-saving methods with a small number of observations (depending on number of observed units and time series length as shown in Table 1) were proposed. In the follow-ing, the most extreme cases, these are modelling methods which focus on only one region (i.e., input–output analyses and time-series analyses) are discussed. These models have to cope with the problem that hypotheses about the poten-tial impacts on waste generation can be proved only in spe-cial cases, if no other sources (e.g., accompanying cross-sectional analyses (e.g., McBean and Fortin, 1993)) are used. The successful identi W cation of seasonal impacts (Matsuto and Tanaka, 1993; Navarro-Esbrí et al., 2002) or weekly collection service patterns (Katsamaki et al., 1998) by applying time-series analyses of daily data over up to 2 years is indisputable. More questionable is the deduction of hypothesised causal impacts in the long term. The identi W-cation of the most signi W cant variable is often assumed to depend on the best relationship between the time series related to waste generation and that related to a factor, although this fact may not have been proven by cross-sec-tional analyses (e.g., OECD, 2004; Skovgaard et al., 2005).

A further potential limitation to the gaining of information is constituted by the missing balance between the sample size and the complexity of a model, as discussed in Section 3.4.

Cost-ine Y cient sampling occurs, if the size of the sample is too high in relation to the needed level of accuracy with-out leading to a signi W cant information gain. Dennison et al. (1996a) conducted 857 sorting analyses on household level, although the calculated required sample size for a 95% con W dence interval was 384 sorting analyses. Abu Qdais et al. (1997) could have avoided 24% of the 840 sam-ples evaluated by selecting the usually applied 95% con W-dence interval instead of a 99% con W dence interval. Furthermore, the ambitious inquiry of waste collection data of Bach et al. (2003) from 1071 municipalities seems to far succeed the statistical requirements of a regression model.

3.2. Waste stream de W nition and investigation

The number and type (cf. Section 2.2) of scoped waste streams, as well as the level of accuracy of discrimination, exert an essential impact on the e V orts to collect waste-related data and the information content of the planning fundamentals.

Depending on the type of waste streams de W ned (collec-tion streams or household waste fractions), experience gained in the reviewed studies suggests bene W cial ranges of the number of observed waste streams in order to identify an appropriate balance between information gain and e V orts. The majority of models based on collection-stream data apply total MSW generation as only one dependent variable. A common variety with two considered collection

P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214207

streams (i.e., dependent variables) is the de W nition of a recy-cling and a commingled stream (Becker, 1999; Martens and Thomas, 1996; Par W tt et al., 2001; Karavezyris et al., 2002). Further often expensive disaggregation into material-related recycling streams (e.g., waste paper and waste glass) does not a V ord any useful information due to the impossi-bility of identifying whether varying collection quantities (e.g., in time or between regional units) are subject to a di V erent level of a Z uence or to di V erent recycling quotas. For models based on sorting analyses of household waste, the results showed that 6 up to 14 main categories are su Y-cient for evaluations. It is not advantageous to consider more categories or sub-categories of fractions as needed for the study objective, as done by Emery et al. (2003) with 30 sorting categories. If input–output analyses are applied, no recommendations can be given as the number of considered material and product streams depend on the amount of detail provided by data sources.

Insu Y cient de W nition and standardisation of MSW is a well known problem, and experiences concerning the di V er-ences between MSW and household waste have been reported (Fischer and Crowe, 2000). Frequently, the inves-tigated waste streams are not transparently de W ned, so it is hardly comprehensible which (collection or material-related) streams are covered and how much information exists concerning the quantity and quality of the excluded streams. Related limitations were openly reported in only a few cases. One of these was the criticism made by Par W tt and Flowerdew (1997) of the United Kingdom’s National Household Waste Analysis Programme, who stated that the de W ned term “household waste” covered only the waste from curbside collection, while 33% of the household waste, mainly from civic amenity sites, had not been taken into consideration due to the inappropriate sampling procedure. Without any quantitative information as to the separately collected materials in three settlement areas, E mery et al. (2003) traced the lowest amount of newspapers in house-hold waste in the highest-income settlement area back to the fact of high recycling rates because “newspapers pur-chased by more a Z uent households tend to be larger”. In both cases, the inclusion of collection data other than that pertaining to curbside collection sites would close this gap between the curbside collected stream and the complete col-lection stream.

Distortions of MSW streams related to other sources (e.g., commercial waste, tourism) or waste-related activities (private burning of waste, illegal disposal) remain sub-merged, but can be successfully estimated using appropriate proxy variables as described in Section 2.3 (cf. Hockett et al., 1995).

3.3. Selecting independent variables to be hypothesised

Still in the conception stage of model development, it can often be pre-estimated whether a draft model with a de W ned set of hypothesised variables will be able to satisfy the basic information needs of waste management planners: timeli-ness of data, applicability for predictions and su Y cient data quality. Appropriately quick reactions on new waste genera-tion trends require the provision of models based on timely databases. Here the delay between reference year of the last observed waste-related data and the publication year was taken as benchmark. In most models, a delay of up to 3 years was reported. It is notable that models based on exten-sive databases, namely input–output analyses and selected multiple regression models with a high number of hypothes-ised factors, are far from serving relevant up-to-date infor-mation. A comparison of the reference year of core databases and the W rst publication date of each study proves delays of 7 (Brahms and Schwitters, 1985), 9 (Patel et al., 1998), 10 (Joosten et al., 2000; Hekkert et al., 2000) up to 12 years (Bach et al., 2003). Thus this di V erence points out the relevance of the up-to-date nature of existing primary data in order to support the strategic decisions based thereon. The necessity of up-to-date data can be supported with the considerable changes based on time-series data of European countries from the years 1995–2003; the growth of MSW generation within 8 years ranges up to 50% (e.g., Ireland, Malta), while source-separated waste streams nearly triple in some cases (e.g., paper and cardboard collected in France, Italy and Ireland or organic waste collected in France) (European Communities, 2005).

The main objective of several models is to provide a pre-diction tool. The reader should be enabled to make inter-temporal forecasts or inter-regional predictions. Unfortu-nately, the majority of these models are often unusable due to the lack of underlying data for the model parameters. For example, forecasted values for variables, such as prod-uct-related fractions of total consumer expenditures on a national level (Daskalopoulos et al., 1998) or actual indices of purchasing power per capita on a municipal level (Bach et al., 2004), are very probably not available for the waste management planners. A useful solution to this problem is proposed by Skovgaard et al. (2005), who provide forecasts for all necessary predictors for MSW forecasts to potential users. Further improvement can be gained by the use of parameters which are both easily comparable and predict-able, such as socio-economic variables (cf. Section 4.2).

The more independent variables are hypothesised, col-lected and evaluated, the more di Y cult it is to guarantee a level of data quality. The implementation of data-intensive approaches can be signi W cantly limited or aggravated by problems of data availability and comparability. Further to the above mentioned problems of data obsolescence, incon-sistent de W nitions and a lack of data are cost-relevant drivers, especially for input–output analyses based on up to thou-sands of independent variables. With reference to indirect waste analyses using market-research data, Fehringer et al. (2004) pointed out the cost-e V ectiveness of this method, whilst stating, however, that “the greater the lack of data, the more time and e V ort has to be put in to achieve reasonable results”. Assumptions and estimations usually have to be made to allocate mass X ows within product groups, to trans-form prices into physical units (cf. Gay et al., 1993) and to

208P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214

assume residence times per product (cf. Patel et al., 1998). A possible countermeasure would be to check data availability and comparability during a preliminary examination prior to the W nal de W nition of research design.3.4. Model validation

The accuracy of model results (i.e., the main model char-acteristics and selection criterion for practitioners of pre-diction tools according to Armstrong, 2001) can be limited or distorted for two reasons: insu Y cient validation of model and model parameters and lack of balance between oversimpli W cation and over W tting.

3.4.1. Validation with waste data

In the present paper, model validity is de W ned as internal validity or the capability of the model to explain the depen-dent variable ‘waste quantity’. It has an indirect, although not constraining, impact on the more relevant external validity, i.e., the ability to generalise the results obtained to di V erent temporal or spatial settings.

While validity was tested for group comparisons, correla-tion and regression models by means of common statistical tests, comprehensive validity tests were not conducted for all reviewed system dynamics models and input–output models.The reviewed system dynamics models enable simulations of interconnected variables, whose hypothesised relationships (e.g., between household size and waste generation) are deter-ministically de W ned, but not stochastically tested. Input–out-put analyses are also deterministic models, which are typically not based on stochastically assumed variables.3.4.2. Balancing model complexity

Waste generation models that are either exceedingly sim-ple or too complex can provide inappropriate results. The level of complexity necessary depends on both the number

of applied parameters and their functional form. An unfa-vourable ratio between the identi W ed degrees of freedom to the sample size may cause over W tting or oversimpli W cation of the model (Tabachnik and Fidell, 1989).

Models with an excessively high number of partly non-linear parameters tend to unduly W t to the data in the sam-ple. The impact of over W tting of intercorrelated variables to variations due to measurement errors maximises the per-centage of variance explained (e.g., correlation coe Y cient),but limits the ability of the results to be generalised. With the exception of model-speci W c tests (e.g., collinearity tests and tests of residues), the fundamental rule that the sample size should exceed more than twofold the number of parameters (Backhaus et al., 2003) may be of help in orien-tation. Indeed, the application of this condition strengthens the suspicion that Jenkins’ (1993) 27-parametric forecasting model for the separate estimation of both residential and commercial waste based on only nine areas may be a V ected by this phenomenon. Table 3 shows how the sample size of multiple regression models typically exceeds by 30-fold up to 90-fold the number of parameters. Furthermore, the seemingly arbitrary selection of non-linear regression func-tions of higher order, as presented by Daskalopoulos et al.(1998), Bogner et al. (1993) and Bach et al. (2004), should be transparently justi W ed with objective relationships between the variables to prove that they are not based solely on the maximisation of R 2. An additional problem may be represented by the increased di Y culty of interpret-ing models with more than ten parameters, likely implying a decreased practicability for waste managers.

On the contrary, the potential information gain could easily be increased in the case of an oversimpli W ed model design. Extensive survey-based databases, e.g., from Denni-son et al. (1996a), could be used in multivariate procedures instead of single correlation analysis, as proposed by Leber-sorger (2004), in order to ascertain existing relationships

Table 3

Models based on multivariate regression equations n.c. – no comment.a

Time series from 55 cities.b

Includes waste from the residential and commercial sector.c

Time series from 9 communities.d

13 regressors and 14 regional dummy variables.

Reference Dependent variable (in kg/cap/yr,if not otherwise stated)

Sample size (n )Identi W ed parameters Explained variance (R 2)Bach et al. (2003)

Residual waste 1071140.50Waste glass

50770.53Light weight packaging – collected in bringsystem 7130.400Light weight packaging – curbside collection 21670.388Waste metals

15670.538Bach et al. (2004)Waste paper 64980.487Beigl et al. (2004)

MSW

550a 60.65Grossman et al. (1974)MSW (Gallons/week)10330.36Hockett et al. (1995)MSW

10020.497Jenkins (1993)

Residual waste b (Pounds/cap/month)600c 27d 0.921Residual waste b (Pounds/cap/year)49c 27d 0.998Salhofer and Graggaber (1999)

MSW

118

4

n.c.

P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214209

between variables. Time-series based forecasting models taking into account no (Chen and Chang, 2000) or only one (Chang and Lin, 1997) exogenous impact could easily be improved by the inclusion of one or more a Z uence-related census variable (e.g., based on parallel cross-sectional anal-yses) in order to increase long-term predictability.3.5. Guideline development

Fig.2 shows the guideline developed on the basis of the aforementioned W ndings for the evaluation of the research designs. This can be applied both in checking a waste gener-ation model prior to implementation or for evaluating the reliability of existing models.4. Case studies

The selected regional scale of a waste generation model produces the highest impact on type of information gained

and e V orts required. The following two case studies demon-strate the bene W ts and limits of two approaches on both a household and on a city level. In both cases, the application of the developed guideline will be discussed.4.1. Case study 1: modelling on a household level

Case study 1 (cf. Lebersorger, 2004) was aimed at identi-fying in X uencing factors on waste generation from private households and at identifying indicators capable of fore-casting the amount of residual waste from a multifamily dwelling. Prior research had shown highly divergent per-capita quantities of residual waste from multi-family dwell-ings, for which no feasible explanation could be a V orded,even when taking into account the possibility of a di V erent recycling performance or the production of waste from sources other than households, i.e., garden or commercial waste. Thus, a multi-family dwelling was hypothesized as being occupied by households living under similar circum-

Fig.

2. Guideline for the evaluation of research design.

210P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214

stances with regard to income, family-situation, social stra-tum etc., thereby generating similar needs and resulting in similar quantities of residual waste.

For the survey, six multi-family dwellings were selected, each with more than 600 inhabitants and more than 320 households. As dependent variables, the quantities and composition of residual waste were determined at the level of a multi-family dwelling by means of composition analy-ses and weighing the contents of the waste containers. As independent variables, data on socio-demographic charac-teristics and household activities were investigated by means of a questionnaire survey applied to 334 households, thus including at least 50 households from each multi-fam-ily-dwelling.

The determination of waste-related data at the level of a multi-family dwelling was preferred over that of household level due to practical and methodical considerations (cf. Lebersorger et al., 2003):

–availability of aggregated information concerning a large number of households at reasonable costs and

e V ort.

–similar circumstances for all households in a given multi-family dwelling with regard to the recycling system, cost for housing, construction issues, neighbourhood etc.

–little in X uence of the questionnaire survey on the actual behaviour of the household. In multi-family dwellings it is not usually possible to determine waste quantities on a household level without involving the household itself.

The awareness of participating in a scienti W c investiga-tion and the subjective feeling of “being controlled” will likely a V ect the households’ actual behaviour (Haw-thorne or guinea-pig e V ect).

These advantages were considered to outweigh the dis-advantage of not being able to attribute waste data to an individual household.

The data were analysed in two steps by means of contin-gency analyses and multiway frequency analyses.

1.Correlation between the quantity of a de W ned waste

component (data at the level of a multi-family dwelling) and relevant household activities (data at household-level): for example the in X uence of the frequency of food preparation, frequency of wasted food, consumption of fresh food, consumption of pre-packaged food etc. on the quantity of wasted food.

2.Correlation between household consumption activities

and socio-demographic indicators (household type, age, income, life-cycle stage, educational level of the respon-dent), at household level.

Age and household type had an e V ect on most of the household activities, both the main e V ects of either of them and the interaction of the two variables “age” and “house-hold type”. Due to the considerable e V ect produced by the interaction “age” and “household type”, the composite var-iable life-cycle stage (cf. Tabachnik and Fidell, 1989), which classi W es households according to number and age of adults and children, was considered an appropriate indicator. The results obtained illustrated how the presence of a high num-ber of elderly couples and singles was indicative of low waste quantities from a multi-family dwelling, whereas households with infants and schoolchildren were likely to generate the highest waste quantities.

However, population statistics do not generally provide such composite data and interaction e V ects thus cannot be considered. Furthermore, interaction e V ects, particularly three-way or higher e V ects, are very di Y cult to interpret. In terms of practical applicability, the e V ects should be simpli-W ed.

In order to verify the results of the case study, detailed information concerning the socio-demographic characteris-tics and waste quantities from 10 multifamily dwellings, available from a former investigation (cf. Grassinger et al., 2000), were used. Fig.3 shows the correlation between the quantities of residual waste of each multi-family dwelling and the household type and age (Kendall’s tau-b ?0.293; p D0.000***). The higher the percentage share of house-holds with children and the younger the residents, the higher was the waste quantity of the multifamily dwelling, which corroborates the results found in the Viennese case study.

It can be concluded that an investigation performed on both a multifamily-dwelling and household level may be of use when applied to clarify a speci W c research issue or to obtain detailed basic information. However, it is not appli-cable on a larger scale due to several limitations. The sam-ple-size is restricted by the e V ort required to determine the waste quantities from a multifamily-dwelling (separate weighing, visual inspections required in order to check potential in X uences on waste quantities such as garden waste or commercial waste), as well as the e V ort needed to survey the residents.

4.2. Case study 2: modelling on a city level

The objective of case study 2 (cf. Beigl et al., 2004) was the development of a long-term forecasting tool for the esti-mating of MSW generation in E uropean cities. It was aimed at W nding a suitable compromise between an appro-priate level of accuracy and validity, and a comparable ease of applicability by municipal o Y cers as targeted users. The central hypothesis postulated a relationship between cen-sus-based, a Z uence-related indicators and both the quan-tity of per-capita MSW generation.

An investigation carried out in association with six regional partners assessed the collection and inspection of waste-related data, as well as demographic and socio-eco-nomic indicators, in all major E uropean cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants. Both regional data at city levels provided from local city representatives and national data from international organisations, such as the United Nations or OECD, were used. Based on the availability and

P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214211

quality of data, 55 cities (from a total of 65) from the EU-25 countries were included in the study; these cities pre-sented an average time-series length of 10 years in the sam-ple providing both total MSW quantity and results for 14 national and city-related socio-economic indicators.

The selection of this research design based on cross-sec-tional time-series data on a city level was derived from the following practical and methodological considerations:

–waste generation on a city level serves as primary plan-ning information,

–data quality on a city level was assumed to have highest data quality for small regions (cf. Petersen et al., 1999),–knowledge of the time-shifted long-term developments of waste generation and potential impacts was hypothes-ised by the authors to be generalisable for cities with a similar welfare level,

–availability of time series enabled testing of the W nal model under real conditions.

Data analyses were carried out in two steps:

–Attribution of datasets to welfare-related groups using hierarchical cluster analyses: Each single dataset from a total of 550, representing the total MSW generation of a speci W c city in 1 year, was attributed to groups in order to fade out high welfare di V erences. Additionally, a pros-perity-related factor was modelled by means of principal component analysis.

–Regression between total MSW generation and indica-tors: For each of the three groups, regression equations were estimated using combined forward and backward regression. The most signi W cant, not inter-correlated variables were identi W ed. Tests of collinearity, autocorre-lation and residual analyses agreed with the regression assumptions.

Both welfare-related and demographic indicators were identi W ed as the most signi W cant parameters to explain the

Table 4

Prosperity-related regression models for total MSW generation in European cities

a Except the logarithmic relationship of the infant mortality rate.

b National indicators.Prosperity level

Medium High Very high

Identi W ed linear a model parameters on the dependent variable MSW generation (kg/cap/yr) (ranked in order of signi W cance)

Constant?360.657276.529359.536 GDP per capita (US-$ PPP, 1995 prices)0.0156b0.014b Infant mortality rate (Deaths per 1000)?375.581b?126.485?197.057 Urban population aged 15–59 years (%)8.928

Household size (Pers/hh)?123.895

Life expectancy at birth (Years)11.702

Coe Y cient of determination (R2)0.6000.5230.506 Limits and threshold values between groups (Approximate values resulting from hierarchical cluster analyses)

GDP per capita (US-$ PPP, 1995 prices)300013,80020,20040,000 Infant mortality rate (Deaths per 1000)208.1 6.3 3.5

212P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214

variation of total MSW generation. While the gross domes-tic product and infant mortality rate were identi W ed as sig-ni W cant parameters for high-income cities, the age structure, household size and both health indicators (i.e., infant mortality rate and life expectancy at birth) proved capable of explaining variations observed in medium-income cities (Table 4).

In order to verify the expected forecasting accuracy, the dynamic modi W cation of the model was tested by means of ex-post forecasting. Thus the development of the actual MSW quantity was compared with the amount estimated using the model parameter, and starting from a de W ned base year. The median relative error of the growth rate in MSW quantity of all cities’ time series (ranging between a length of 5 and 21 years) as key indicator for the accuracy amounted for 0.6%.

Based on a comparison of the procedure and the results with other forecasting tools by Beigl et al. (2004, 2005), it can be surmised that both the regional variation between cities on similar welfare-level and the temporal variation can be explained more suitably than with pure cross-sec-tional analyses (Bach et al., 2004), which do not allow for validation tests, and single time series analyses (e.g., Skovg-aard et al., 2005), which may be increasingly a V ected by measurement errors, especially in short time series. An additional bene W t is the comparably ready availability of the applied demographic forecast data for the independent variables (cf. Lindh, 2003).

5. Conclusions

Assessments of impacts on current and future waste streams are essential and indispensable fundamentals in waste management planning. A literature review of previ-ously published approaches revealed a high heterogeneity of applied models, in spite of the fact that issues to be solved were remarkably similar. These models can best be described by four speci W c criteria: the focussed regional scale, ranging from household up to country perspective; the type of modelled waste streams; the hypothesised inde-pendent variables and the modelling method.

A procedural guideline was developed in order to iden-tify crucial design options with signi W cant impacts on infor-mation gain and cost-e Y ciency of waste generation models. Based on a discussion of previous studies, bene W cial choices concerning regional sampling (i.e., number and size of observed areas), waste stream de W nition and investigation, selection of independent variables and model validation procedures were proposed. The implementation of the derived W ndings was practically demonstrated in two case studies with di V erent settings: a survey-based analysis of household waste generation at multi-family dwellings and a census-data-based development of a forecasting tool for cities. The comparison of both approaches corroborates the hypothesis that, due to the presence of various planning issues, the use of only one ‘optimum’ procedure is not su Y-cient for di V erent study objectives and border conditions. The setting of minimum requirements and criteria for mod-elling procedures should balance information gain and implementation costs.

Beside these general checklist-like recommendations, the adaptation of overall model design to the planning problem plays a fundamental role. The discussion revealed several shortcomings concerning the choice of methods to be used. Fig.4 shows a proposed relevance tree for appropriate methodology selection. The main selection criterion is the type of waste streams to be investigated. In the majority of cases, correlation and regression analyses, as well as group comparisons, are the most bene W cial modelling methods, both to test the relationship between the level of a Z uence and the generation of total MSW or a material-related frac-tion, and to identify signi W cant e V ects of waste management activities on recycling quotas. The application of time series analyses and input–output analyses is advantageous for special information needs (e.g., assessment of seasonal e V ects for short-term forecasts) or for appropriate data

P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214213

availability. Sorting analyses are indispensable, if impacts on the quantity of separately collected waste streams (e.g., of recyclables) are to be quanti W ed.

References

AbuQdais, H.A., Hamoda, M.F., Newham, J., 1997. Analysis of residential waste at generation sites. Waste Management and Research 15 (4), 395–406.

Armstrong, J.S., 2001. Principles of Forecasting: A Handbook for Researchers and Practitioners. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Norwell, USA. p. 369.

Bach, H., Mild, A., Natter, M., Weber, A., 2004. Combining Socio-demo-graphic and logistic factors to explain the generation and collection of waste paper. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 41 (1), 65–73. Bach, H., Weber, A., Mild, A., Natter, M., Hausberger, S., 2003. Optimi-erungspotentiale in der Entsorgungslogistik (optimisation potentials in waste logistics). Schriftenreihe Umweltschutz und Ressourcen?kono-mie Published By Department of Technology and Commodity Science (vol. 40). Vienna, Austria.

Backhaus, K., E richson, B., Plinke, W., Weiber, R., 2003. Multivariate Analysemethoden (Multi-variate Analysis Methods). Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

Becker, S., 1999. Modell-E ntwicklung für Abfallprognosen auf Soziode-mographischer Basis (Model Development for Waste Prognoses Based on Socio-demographics). Master of Science Thesis, University of Essen, Essen, Germany.

Beigl, P., Gamarra, P. and Linzner, R., 2005. Waste forecasts without ‘rule of thumb’: improving decision-support for waste generation estima-tions. In: Proceedings Sardinia 2005, Tenth International Waste Man-agement and Land W ll Symposium, S. Margherita di Pula, Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy.

Beigl, P., Wassermann, G., Schneider, F. and Salhofer, S. 2003. Municipal solid waste generation trends in European countries and cities. In: Pro-ceedings Sardinia 2003, Ninth International Waste Management and Land W ll Symposium, S. Margherita di Pula, Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy. Beigl, P., Wassermann, G., Schneider, F. and Salhofer, S. 2004. Forecasting municipal solid waste generation in major european cities. In: Pahl-Wostl C., S. Schmidt, and T. Jakeman. (E ds.), iE MSs 2004 Interna-tional Congress: “Complexity and Integrated Resources Manage-ment”. Osnabrueck, Germany.

Bogner, J., Matthews, E., 2003. Global methane emissions from land W lls: new methodology and annual estimates 1980–1996. Global Biogeo-chemical Cycles 17 (2), 1–34.

Bogner, J., Rathje, W., Tani, M. and Minko, O., 1993. Discards as mea-sures of urban metabolism: the value of rubbish. Paper Presented at Symposium on Urban Metabolism, University of Michigan. Popula-tion Econ. Dyn. Project, Kobe, Japan.

Brahms, E. and Schwitters, H. 1985. Hausmüllaufkommen und Sekund?r-statistik (Household Waste Generation and Secondary Statistics).

UBA-FB 84-097, Report No. 103 03 507. Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

Chang, N.-B., Lin, Y.T., 1997. An analysis of recycling impacts on solid waste generation by time series intervention modeling. Resources, Con-servation and Recycling 19 (3), 165–186.

Chen, H.W., Chang, N.-B., 2000. Prediction analysis of solid waste genera-tion based on grey fuzzy dynamic modelling. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 29 (1–2), 1–18.

Christiani, J., 1997. Kreislaufwirtschaft nach dem Muster der Ver-packungsverordnung: Untersuchungen zu Umsetzung und Perspekti-ven unter besonderer Berücksichtigung aufbereitungstechnischer und abfallwirtschaftlicher Gesichtspunkte (Closed-loop E conomy on the Pattern of the Packaging Regulation: Investigations to Implementa-tion and Perspectives with Special Consideration of Process-technical and Waste-economical Criteria). PhD Thesis at the RWTH Aachen.

Shaker Verlag, Aachen, Germany.Christiansen, K.M. and Fischer, C. 1999. Baseline projections of selected waste streams: developments of a methodology. European

E nvironmental Agency, Technical Report No. 28, Copenhagen,

Denmark.

Daskalopoulos, E., Badr, O., Probert, S.D., 1998. Municipal solid waste: a prediction methodology for the generation rate and composition in the

E uropean Union countries and the United States of America.

Resources, Conservation and Recycling 24 (1), 155–166.

Dennison, G.J., Dodd, V.A., Whelan, B., 1996a. A socio-economic based survey of household waste characteristics in the city of Dublin, Ireland,

I. Waste composition. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 17 (3),

227–244.

Dennison, G.J., Dodd, V.A., Whelan, B., 1996b. A socio-economic based survey of household waste characteristics in the city of Dublin, Ireland, II. Waste quantities. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 17 (3), 245–257.

Dyson, B., Chang, N.-B., 2005. Forecasting municipal solid waste genera-tion in a fast-growing urban region with system dynamics modelling.

Waste Management 25 (7), 669–679.

Eder, G., 1983. Ein X ussgr??enuntersuchung zum Abfallverhalten privater Haushalte (Investigation of In X uencing Factors on the Waste-related Habits of Private Households). Project Report No. 103 03 503, Umweltbundesamt Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

E mery, A.D., Gri Y ths, A.J., Williams, K.P., 2003. An in depth study

of the e V ects of socio-economic conditions on household waste recycling practices. Waste Management and Research 21 (3), 180–190.

E uropean Commission (E C), 2002. Development of a Methodological

Tool to E nhance the Precision and Comparability of Solid Waste Analysis Data, Statistical Test of the Strati W cation Criteria Parameter.

VK4-CT-2000-00030, internal report.

E uropean Communities (E C), 2005. Waste Generated and Treated in

Europe – Data 1995–2003. O Y ce for O Y cial Publications of the Euro-pean Communities. Luxembourg.

Fehr, M., de Castro, M.S.M.V., Cal?ado, M.D.R., 2000. A Practical solu-tion to the problem of household waste management in Brazil.

Resources, Conservation and Recycling 30 (3), 245–257.

Fehringer, R., Brandt, B., Brunner, P.H., Daxbeck, H., Neumayer, S., Smutny, R., Villeneuve, J., Michel, P., Kranert, M., Schultheis, A. and Steinbach, D., 2004. MFA-Manual – Guidelines for the Use of Mate-rial Flow Analysis for Municipal Solid Waste Management. E VK4-CT-2000-00015.

Fischer, C. and Crowe, M., 2000. Household and municipal waste: compa-rability of data in EEA member countries. Topic Report No 3. Euro-pean Environment Agency, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Franklin Associates, 1999. Characterization of municipal waste in the United States: 1998 Update. E PA530-R-99-021. US E nvironmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA.

Gay, A.E., Beam, T.G., Mar, B.W., 1993. cost-e V ective solid-waste charac-terization Methodology. Journal of E nvironmental E ngineering 119

(4), 631–644.

Grassinger, D., Lebersorger, S., Salhofer, S. and Trimmel, M., 2000. Opti-mierung der getrennten Sammlung von Abf?llen in Wohnhausanlagen (Optimising the separate collection of waste in multifamily dwellings).

Research project on behalf of the municipalities of Schwechat, Baden, Bruck and Tulln, unpublished, Vienna.

Grossman, D., Hudson, J.F., Mark, D.H., 1974. Waste generation methods for solid waste collection. Journal of E nvironmental E ngineering, ASCE 6, 1219–1230.

Haase, H., 2000. Methode und Ergebnisse einer Aufkommensprognose für den Restabfall zur Beseitigung im Regierungsbezirk Magdeburg (methodology and results of a waste prognosis for residual waste in the district of Magdeburg). Müll und Abfall 7, 419–430.

Hekkert, M.P., Joosten, L.A.J., Worrell, E., 2000. Analysis of the paper and wood X ow in the Netherlands. Resources, Conservation and Recycling

30 (1), 29–48.

214P. Beigl et al. / Waste Management 28 (2008) 200–214

Hockett, D., Lober, D.J., Pilgrim, K., 1995. Determinants of per capita municipal solid waste generation in the Southeastern United States.

Journal of Environmental Management 45 (3), 205–217.

Jenkins, R.R., 1993. The E conomics of Solid Waste Reduction: The Impact of User Fees. E dward E lgar Publishing Limited, Aldershot, United Kingdom.

Joosten, L.A.J., Hekkert, M.P., Worrell, E., 2000. Assessment of the plastic X ows in the Netherlands using STRE AMS. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 30 (2), 135–161.

Joosten, L.A.J., Hekkert, M.P., Worrell, E., Turkenburg, W.C., 1999.

STREAMS: a new method for analysing material X ows through soci-ety. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 27 (3), 249–266. Karavezyris, V., 2001. Prognose von Siedlungsabf?llen: Untersuchung zu determinierenden Faktoren und methodischen Ans?tzen (Prognosis of Municipal Solid Waste: Investigation of the Determinating Factors and Metholodogical Approaches). TK Verlag, Neuruppin, Germany.

Karavezyris, V. and Marzi, R. 1999. Employing knowledge acquisition in the domain of long-term prognosis of municipal waste. In: Proceedings of HELECO ‘99 Conference, 61–68.

Karavezyris, V., Timpe, K., Marzi, R., 2002. Application of system dynam-ics and fuzzy logic to forecasting of municipal solid waste. Mathemat-ics and Computers in Simulation 60 (3–5), 149–158.

Katsamaki, A., Willems, S., Diamadopoulos, E., 1998. Time series analysis of municipal solid waste generation rates. Journal of E nvironmental Engineering 124 (2), 178–183.

Leao, S., Bishop, I., Evans, D., 2001. Assessing the demand of solid waste disposal in urban region by urban dynamics modelling in a gis environ-ment. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 33 (4), 289–313. Lebersorger, S., 1998. Entsorgungsgewohnheiten von Haushalten am Bei-spiel Waidhofen an der Thaya (Disposal Habits of Households taking Waidhofen upon Thaya as Example). Master of Science Thesis, BOKU – University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria.

Lebersorger, S., 2004. Abfallaufkommen aus Mehrfamilienh?usern. Ana-lyse der Ein X ussfaktoren unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Leb-ensumst?nde und Lebensgewohnheiten privater Haushalte (Waste Generation of Multi-Family Dwellings. Analysis of In X uencing Fac-tors under Special Consideration of the Living Conditions and Habits of Private Households). Doctoral Thesis, BOKU – University of Natu-ral Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria. Lebersorger, S., Schneider, F. and Hauer, W., 2003. Waste generation in households – models in theory and practical experience from a case study of multifamily dwellings in Vienna. In: Proceedings Sardinia 2003, Ninth International Waste Management and Land W ll Sympo-sium, S. Margherita di Pula, Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy.

Lindh, T., 2003. Demography as a forecasting tool. Futures 35 (1), 37–48. Martens, B., Thomas, J., 1996. Ein X u?faktoren des Abfallaufkommens aus Privathaushalten in Baden-Württemberg (in X uencing factors on waste generation of private households in Baden-Wuerttemberg). Zeitschrift für Umweltpolitik und Umweltrecht 2, 243–259.

Matsuto, T., Tanaka, N., 1993. Data analysis of daily collection tonnage of residential solid waste in Japan. Waste Management and Research 11

(4), 333–343.

McBean, E.A., Fortin, M.H.P., 1993. A forecast model of refuse tonnage with recapture and uncertainty bounds. Waste Management and Research 11 (5), 373–385.

Mertins, L., Vinolas, C., Bargallo, A., Sommer, G. and Renau, J. 1999.

Development and application of waste factors – An overview. Techni-cal Report 37. European Environmental Agency, Copenhagen. Cited in: Bogner J. and E. Matthews, 2003. Global Methane Emissions from

Land W lls: New Methodology and Annual Estimates 1980–1996, Glo-bal Biogeochemical Cycles 17 (2), 34–1.

Morrissey, A.J., Browne, J., 2004. Waste management models and their application to sustainable waste management. Waste Management 24

(3), 297–308.

Navarro-E sbrí, J., Diamadopoulos, E., Ginestar, D., 2002. Time series analysis and forecasting techniques for municipal solid waste manage-ment. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 35 (3), 201–214. Organisation for E conomic Co-operation and Development (OE CD), 2004. Towards Waste Prevention Performance Indicators. E NV/

E POC/WGWPR/SE(2004)1/FINAL. E nvironment directorate, Paris,

France.

Par W tt, J.P., Flowerdew, R., 1997. Methodological problems in the genera-tion of household waste statistics. Applied Geography 17 (3), 231–244. Par W tt, J.P., Lovett, A.A., Sünnenberg, G., 2001. A classi W cation of local authority waste collection and recycling strategies in E ngland and Wales. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 32 (3-4), 239–257. Patel, M.K., Jochem, E., Radgen, P., Worrell, E., 1998. Plastic streams in Germany – an analysis of production, consumption and waste genera-tion. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 24 (3–4), 191–215. Petersen, R., Ravn, A. and Mortensen, N.H., 1999. Report on an Overall Data Model for ETC/Waste. Technical Report No 23, p. 33. European Environment Agency, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Pladerer, C., 1999. E ntsorgungsgewohnheiten von Privathaushalten am Beispiel Wien (Disposal Habits of Households taking Vienna as Exam-ple). Master of Science Thesis, BOKU – University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria.

Rhyner, C.R., Green, B.D., 1988. The predictive accuracy of published solid waste generation factors. Waste Management and Research 6 (4), 329–338.

Ru V ord, N.M., 1984. The Analysis and Prediction of the Quantity and Composition of Household Refuse. Unpublished PhD Thesis, The University of Aston, UK. Cited in: Par W tt, J.P., R. Flowerdew, 1997.

Methodological problems in the generation of household waste statis-tics. Applied Geography 17 (3), 231–244.

Salhofer, S., 2001. Kommunale E ntsorgungslogistik: Planung, Gestaltung und Bewertung entsorgungslogistischer Systeme für kommunale Abf?lle (Municipal Waste Logistics: Planning, Design and Evaluation of Waste-Logistic Systems for Municipal Wastes). Erich Schmidt, Berlin. Salhofer, S., Graggaber, M., 1999.

E

rhebung des kommunalen Abfallaufkommens und Untersuchung ausgew?hlter Sammelsysteme im Bundesland Salzburg (Data Collection of Municipal Solid Waste Generation and Investigation of Selected Collection Systems in the Region Salzburg). Project Report on Behalf of the Federal State of Salzburg, unpublished, Vienna, Austria.

Schar V, C., 1991. Entwicklung und Anwendung von Methoden zur sto V-und warenorientierten Analyse von Abfallstr?men (Development and Application of Methods to Material and Product-orientated Analyses of Waste Streams). Doctoral Thesis, Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration, Vienna, Austria.

Sircar, R., E wert, F., Bohn, U., 2003. Ganzheitliche Prognose von Sied-lungsabf?llen (holistic prognosis of municipal wastes). Müll und Abfall 1, 7–11.

Skovgaard, M., Moll, S., Andersen, F.M., Larsen, H., 2005. Outlook for waste and material X ows: baseline and alternative scenarios. Working Paper 1. European Topic Centre on Resource and Waste Management, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Tabachnik, B.G., Fidell, L.S., 1989. Using Multivariate Statistics. Harper and Row, New York, USA.

Thogersen, J., 1996. Wasteful food consumption: trends in food and pack-aging waste. Scandinavian Journal of Management 12, 291–304.

门禁系统使用说明书

安装、使用产品前,请阅读安装使用说明书。 请妥善保管好本手册,以便日后能随时查阅。 GST-DJ6000系列可视对讲系统 液晶室外主机 安装使用说明书 目录 一、概述 (1) 二、特点 (2) 三、技术特性 (3) 四、结构特征与工作原理 (3) 五、安装与调试 (5) 六、使用及操作 (10) 七、故障分析与排除 (16) 海湾安全技术有限公司

一概述 GST-DJ6000可视对讲系统是海湾公司开发的集对讲、监视、锁控、呼救、报警等功能于一体的新一代可视对讲产品。产品造型美观,系统配置灵活,是一套技术先进、功能齐全的可视对讲系统。 GST-DJ6100系列液晶室外主机是一置于单元门口的可视对讲设备。本系列产品具有呼叫住户、呼叫管理中心、密码开单元门、刷卡开门和刷卡巡更等功能,并支持胁迫报警。当同一单元具有多个入口时,使用室外主机可以实现多出入口可视对讲模式。 GST-DJ6100系列液晶室外主机分两类(以下简称室外主机),十二种型号产品: 1.1黑白可视室外主机 a)GST-DJ6116可视室外主机(黑白); b)GST-DJ6118可视室外主机(黑白); c)GST-DJ6116I IC卡可视室外主机(黑白); d)GST-DJ6118I IC卡可视室外主机(黑白); e)GST-DJ6116I(MIFARE)IC卡可视室外主机(黑白); f)GST-DJ6118I(MIFARE)IC卡可视室外主机(黑白)。 1.2彩色可视液晶室外主机 g)GST-DJ6116C可视室外主机(彩色); h)GST-DJ6118C可视室外主机(彩色); i)GST-DJ6116CI IC卡可视室外主机(彩色); j)GST-DJ6118CI IC卡可视室外主机(彩色); k)GST-DJ6116CI(MIFARE)IC卡可视室外主机(彩色); GST-DJ6118CI(MIFARE)IC卡可视室外主机(彩色)。 二特点 2.1 4*4数码式按键,可以实现在1~8999间根据需求选择任意合适的数字来 对室内分机进行地址编码。 2.2每个室外主机通过层间分配器可以挂接最多2500台室内分机。 2.3支持两种密码(住户密码、公用密码)开锁,便于用户使用和管理。 2.4每户可以设置一个住户开门密码。 2.5采用128×64大屏幕液晶屏显示,可显示汉字操作提示。 2.6支持胁迫报警,住户在开门时输入胁迫密码可以产生胁迫报警。 2.7具有防拆报警功能。 2.8支持单元多门系统,每个单元可支持1~9个室外主机。 2.9密码保护功能。当使用者使用密码开门,三次尝试不对时,呼叫管理中 心。 2.10在线设置室外主机和室内分机地址,方便工程调试。 2.11室外主机内置红外线摄像头及红外补光装置,对外界光照要求低。彩色 室外主机需增加可见光照明才能得到好的夜间补偿。 2.12带IC卡室外主机支持住户卡、巡更卡、管理员卡的分类管理,可执行 刷卡开门或刷卡巡更的操作,最多可以管理900张卡片。卡片可以在本机进行注册或删除,也可以通过上位计算机进行主责或删除。

VISUAL BASIC数据类型的定义

一、数据类型概述 数据:计算机能够处理数值、文字、声音、图形、图像等信息,均称为数据。 数据类型:根据数据描述信息的含义,将数据分为不同的种类,对数据种类的区分规定,称为数据类型。数据类型的不同,则在内存中的存储结构也不同,占用空间也不同 VB的基本数据类型: 数值型数据(主要数据类型)日期型字节型 货币型逻辑型字符串型对象型变体型 二、数值数据类型 数值类型分为整数型和实数型两大类。 1、整数型 整数型是指不带小数点和指数符号的数。 按表示范围整数型分为:整型、长整型 (1)整型(Integer,类型符%) 整型数在内存中占两个字节(16位) 十进制整型数的取值范围:-32768~+32767 例如:15,-345,654%都是整数型。而45678%则会发生溢出错误。 (2)长整型(Long,类型符&) 长整数型在内存中占4个字节(32位)。 十进制长整型数的取值范围: -2147483648~+2147483647 例如:123456,45678&都是长整数型。 2、实数型(浮点数或实型数) 实数型数据是指带有小数部分的数。 注意:数12和数12.0对计算机来说是不同的,前者是整数(占2个字节),后者是浮点数(占4个字节) 实数型数据分为浮点数和定点数。 浮点数由三部分组成:符号,指数和尾数。 在VB中浮点数分为两种: 单精度浮点数(Single) 双精度浮点数(Double) (1)单精度数(Single,类型符!) 在内存中占4个字节(32位),,有效数字:7位十进制数 取值范围:负数-3.402823E+38~-1.401298E-45 正数 1.401298E-45~3.402823E+38 在计算机程序里面不能有上标下标的写法,所以乘幂采用的是一种称为科学计数法的表达方法 这里用E或者e表示10的次方(E/e大小写都可以) 比如:1.401298E-45表示1.401298的10的负45次方

浅谈多功能酶标仪选择的要素

近年来,随着多功能酶标仪在国内各高校实验室逐渐推广开来,多功能酶标仪品牌和型号也逐渐多了起来,乱花渐欲迷人眼。除了三大传统优势品牌PE、MD和TECAN,还出现了众多后来者插足此市场,如收购了芬兰雷勃的Thermo、从发光起家的Berthold、针对药筛领域的BMG以及新兴的BioTek等品牌。各品牌都有各自的一个甚至多个系列产品线,特性各不相同,选购时各种技术参数、技术指标令人眼花缭乱。 本文尝试从用户实际使用的角度,探讨应该如何看待花样繁多的参数特性,希望能帮助大家找到真正合适自己的多功能酶标仪。 一、滤片Vs光栅 多功能酶标仪的分类方法众多,但最简单的莫过于用他们的滤光方式来作分界线。一般来说,可以分为滤光片型和光栅型两大类。当然也有一些型号,例如Synergy4和EnVision等,一台机器里面同时装上了滤光片和光栅。但是滤片和光栅并不能同时完成同一个检测,还是想用光栅的时候用光栅,该用滤片的时候用滤片;还有一些实验非用其中一个不可,另一模块实现不了的。所以这类仪器本质上还只是把滤片和光栅放在了一起,并没有使两者糅合而产生新的技术突破。 总体来说,滤片技术由于发展已久,配合二向色镜(其实也就是另一模式的滤光反光滤镜)等光路系统,可以实现大部分实验的需要。目前常规多功能酶标仪中最高的检测灵敏度就是用滤光片型做出来的,例如TECAN Infinite F500的荧光检测的灵敏度可以达到0.04 fmol/孔(荧光素,384孔/80ul)。 但是滤光片型仪器由于受限于滤片的波长和数量限制,不可能满足日益增加的实验类型的检测需要,而且有时需要对物质的吸收、激发和发射光谱进行研究,所以后来就诞生了光栅型的仪器。 最先推出光栅的是MD公司,其光栅习惯上称为单光栅。由于光纯度的不足,在光栅的后面又加入了一组带阻滤片,再把杂光过滤一遍,达到了5×10-4的杂光率,基本与纯粹的滤光片系统一致。后来TECAN 又发展出了双光栅技术,通过两次光栅滤光,杂光率降到了10-6。后来,Thermo、BioTek和PE的部分新款仪器等都使用了类似双光栅技术。由于激发和发射各用了一组双光栅,此类机器又被称为四光栅型多功能酶标仪。 光栅型酶标仪的推陈出新,使得用户在波长选择上不再受限,而且在杂光率、带宽控制等性能上还超越了滤光片系统。例如,TECAN公司在2008年底推出使用了第三代四光栅系统的M1000酶标仪,杂光率降到了2×10-7的新低,还实现了带宽2.5~20nm连续可调。这些都是目前滤光片型酶标仪所不能或者较难实现的。 二、杂光率&波长准确性 光栅型滤光系统俨然已经成为了目前通用性多功能酶标仪的主流,多家厂家共同努力,已经把光栅技术推到了历史新高。在光栅的众多技术参数之中,最关键的无疑就是光栅的杂光率和波长选择的准确性了。 杂光率指得就是光源通过光栅后,得到的光线中,“不需要”的波长的光占所标称波长的光的比例,表征了滤光的纯度。由于光线干涉、衍射等的复杂性,无论使用滤光片还是光栅,杂光都是不可避免的。各种滤光技术的本质就是要想办法把杂光尽可能地去掉。一般来说,滤光片型的杂光率在10-4~10-5之间,光栅型的可以做到10-6~10-7。由于此类杂光是非特异的,而且会直接进入最后的检测器,所以有多少的杂光就会引入多少的随机误差。在荧光等检测过程中,由于检测器存在放大效应,杂光率的干扰也会被指数级放大。因此,杂光率就是一个滤光系统的首要性能指标。 光栅的另一个重要指标就是波长选择的准确性。因为很多检测是依赖于物质在某个波长的特征图谱。就像

F6门禁管理系统用户手册