An X-ray Cluster at Redshift 2.156

An X-ray Cluster at Redshift 2.156?

C.L. Carilli National Radio Astronomy Observatory, P.O. Box O, Socorro, NM, 87801

arXiv:astro-ph/9712253v1 18 Dec 1997

D.E. Harris Smithsonian Astronomical Observatory, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA, 02138 L. Pentericci, H.J.A. R¨ttgering, G.K. Miley, and M.N. Bremer o Leiden Observatory, Postbus 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands

Received

;

accepted

To appear in the Astrophysical Journal (letters) (accepted December 10, 1997)

–2– ABSTRACT

We present X-ray observations of the narrow line radio galaxy 1138?262 at z = 2.156 with the High Resolution Imager (HRI) on ROSAT. Observations at other wave-bands, and in particular extremely high values of Faraday rotation of the polarized radio emission, suggest that the 1138?262 radio source is in a dense environment, perhaps a hot, cluster-type atmosphere. We detect X-ray emission from the vicinity of 1138?262, and we discuss possible origins for this emission. The X-ray, optical, and radio data all favor thermal emission from a hot cluster atmosphere as the mechanism responsible for the X-rays, although we cannot rule out a contribution from the active nucleus. If this interpretation is correct, then 1138?262 becomes the most distant, by far, of known X-ray emitting clusters. The X-ray luminosity for 1138?262 is 6.7±1.3 ×1044 ergs sec?1 for emitted energies between 2 keV and 10 keV. Subject headings: cosmology: large scale structure; galaxies: clusters – active; radio continuum – galaxies; X-rays – galaxies

–3– 1. Introduction

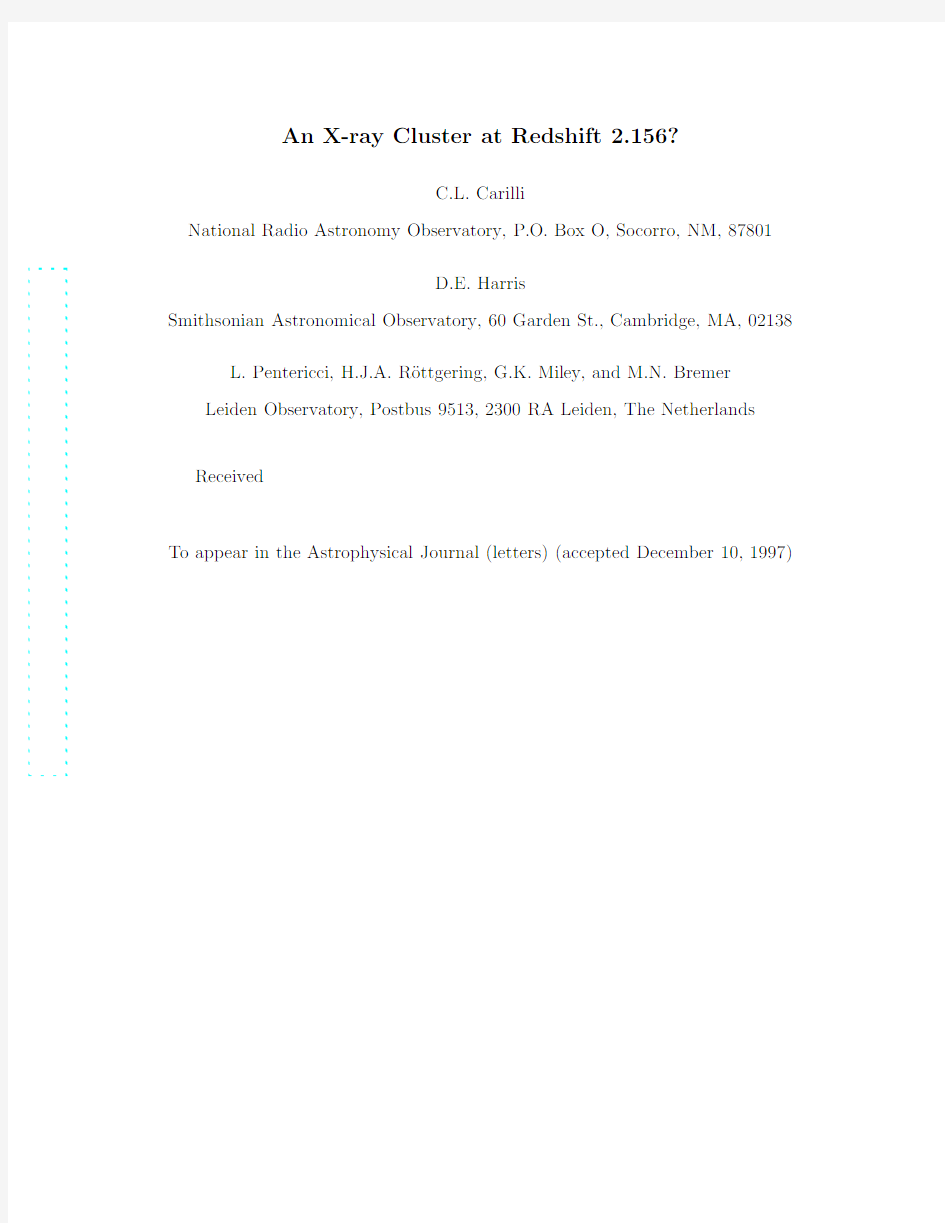

Rich clusters of galaxies constitute the extreme high mass end of the cosmic mass distribution function, and study of such rare objects provides unique leverage into theories of structure formation in the universe (Peebles 1983). Determining the cosmic evolution of the X-ray luminosity function for the hot gaseous atmospheres of rich clusters can constrain both the power spectrum of primordial density ?uctuations, and the mean density of the universe (Oukbir and Blanchard 1997, Oukbir, Bartlett, and Blanchard 1997, Henry 1997). Unfortunately, optical studies of distant clusters can be corrupted by ?eld galaxy contamination (Frenk et al. 1990), while X-ray detections of optically selected clusters have thus far been limited to redshifts less than about one (Ebeling et al. 1997, Castander et al. 1994, Nichol et al. 1997, Luppino and Gioia 1995, Henry et al. 1997). One of the most e?ective methods for ?nding galaxies, and possible clusters, at high redshift is to target steep spectrum radio sources with faint optical counter-parts (McCarthy 1993). Until recently the most distant X-ray emitting cluster detected was that associated with the radio galaxy 3C 295 at z = 0.461 (Henry and Henriksen 1986), and the three most distant X-ray cluster candidates currently known are all associated with powerful radio sources at z ≈ 1 (Crawford and Fabian 1993, Crawford and Fabian 1995, Dickinson 1997). The radio source 1138?262 has been identi?ed with a narrow emission line galaxy at redshift 2.156 (Pentericci et al. 1997, McCarthy et al. 1996). This radio galaxy is remarkable for a number of reasons. First, the optical continuum morphology is comprised of many blue ‘knots’ of emission, distributed over an area of about 100 kpc (Figure 1).1 The Lyα emission shows similar clumpy structure on a similar scale. Second, the radio source has the most disturbed morphology of any z > 2 radio galaxy yet identi?ed,

1

We adopt Ho = 50 km sec?1 Mpc?1 and qo = 0.5.

–4– indicating strong interaction between the radio jet and the ambient medium. And third radio continuum polarimetric imaging of 1138?262 reveals the largest values of Faraday rotation for any radio galaxy at z ≥ 2 (Carilli et al. 1997), with rotation measures as high as 6250 rad m?2 . Such large rotation measures are characteristic of nearby radio galaxies in dense cluster atmospheres (Carilli et al. 1996, Taylor, Ge, and Barton 1994). All these data provide strong, although circumstantial, evidence that the 1138?262 radio source is in a dense environment, perhaps a hot, cluster-type atmosphere. To test this hypothesis we observed 1138?262 with the High Resolution Imager on the ROSAT X-ray satellite.

2.

Observations, Results, and Analysis

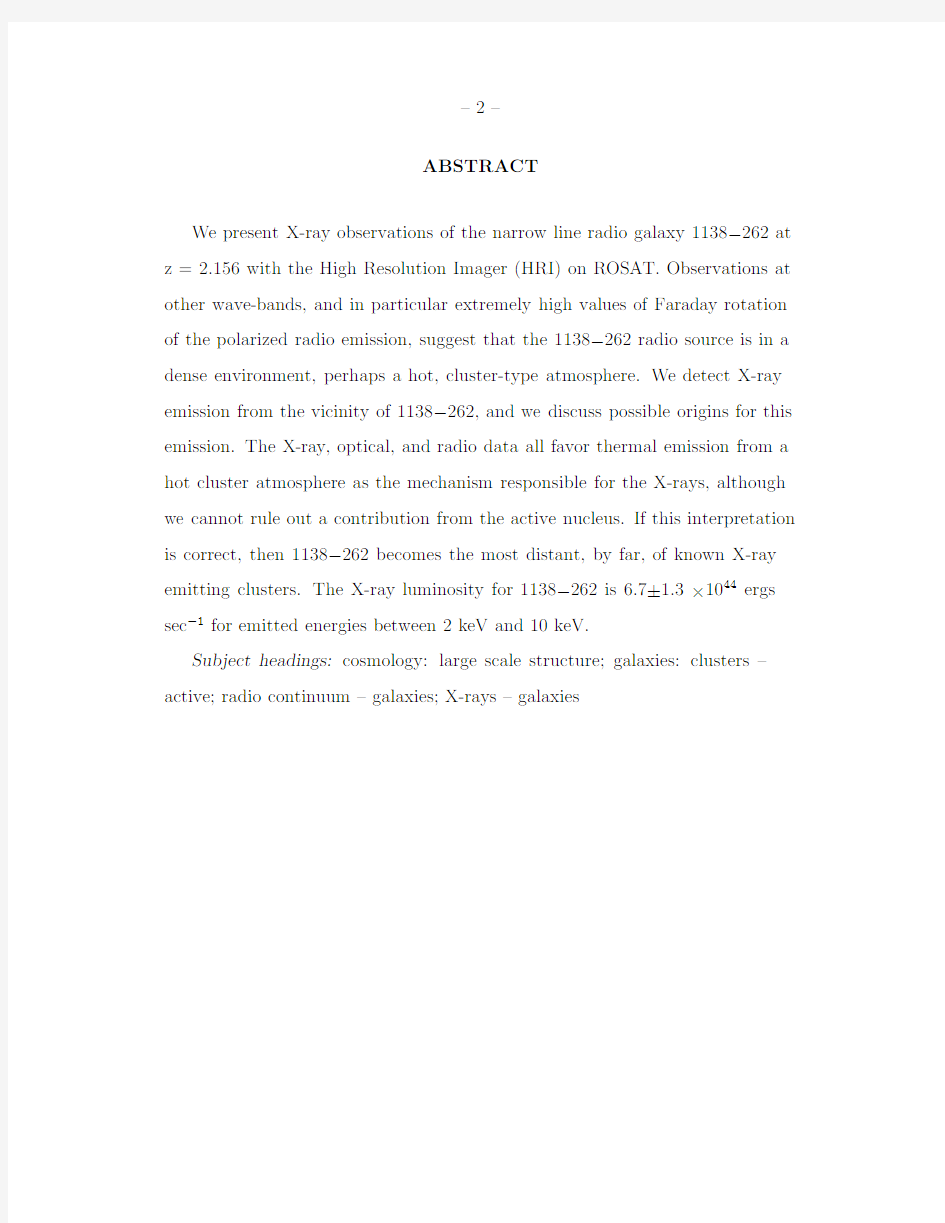

We observed 1138?262 with the High Resolution Imager on the ROSAT X-ray satellite (Tr¨ mper 1983) for 18 ksec on July 13, 1996, and for 23 ksec on June 11, 1997. The u data were reduced using the IRAF-PROS data reduction software at SAO, and the AIPS software at NRAO. The images from each epoch were registered using four ‘background’ X-ray sources within 9′ of the target source. We estimate this relative registration is accurate to about 1′′ . The absolute astrometry was determined using the X-ray and optical star, HD101551, located 9′ northwest of the target source. This astrometry was checked using two other X-ray-optical coincidences in the ?eld. From these we estimate a relative optical-to-X-ray astrometric accuracy of about 3′′ . The ROSAT observations shows a clear detection of an X-ray source close to the position of the radio and optical nucleus of 1138?262 (Figure 2). The separation between the X-ray peak and optical nucleus is 2′′ , which is smaller than the astrometric accuracy. A total of 52 HRI counts were obtained in the optimum detection cell of 21′′ (see below), and the average background in the source vicinity was 21 counts. Hence in the 41 ksec observation the average net HRI count rate from 1138?262 was 0.75±0.16 counts ksec?1 .

–5– An important question concerning the X-ray emission from 1138?262 is whether the emission is spatially extended? We have addressed this question in a number of ways using the three brightest ‘background’ sources within 6′ of 1138?262 for comparison. First, we ?tted an elliptical Gaussian function to the observed brightness distributions of 1138?262, and to the background sources. The results are summarized in Table 1. Columns 2 and 3 list the (deconvolved) Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) values, and the position angle of the major axis. Second, we determined the FWHM for the Gaussian smoothing function which optimizes the detection probability according to Poisson statistics. The FWHM values are listed in column 4 of Table 1, while column 5 lists the net counts. In all cases the size parameters for 1138?262 are larger than those of the background sources, although in the case of the source 5.9′ to the east of 1138?262 the di?erences are within the errors. And third, we calculated the average count rate per 1′′ cell in a series of concentric annuli centered on the position of each source. The resulting radial pro?les are shown in Figure 3. Two of the sources appear to be marginally smaller than 1138?262, again with the exception of the source 5.9′ to the east. Overall, the values in the table, and the radial pro?les, suggest that the X-ray emission from 1138?262 may be more extended than that from the background sources, although in some cases the di?erences are less than the errors. The HRI provides no information on the X-ray spectrum of 1138?262. In order to estimate the total X-ray luminosity from 1138?262, we adopt two di?erent spectral models. The ?rst model is a thermal spectrum with the same parameters as those determined for the X-ray emitting cluster atmosphere enveloping the low redshift radio galaxy Cygnus A: kT = 7 keV and abundance = 30% solar (Reynolds and Fabian 1996, Ueno et al. 1994). Cygnus A was the ?rst extreme rotation measure radio source identi?ed (Dreher et al. 1987), and Cygnus A has a similar radio luminosity to 1138?262. The implied X-ray luminosity for 1138?262 is 6.7±1.3×1044 ergs sec?1 for emitted energies between 2 keV and 10 keV. For comparison, the luminosity for the Cygnus A cluster in this band is 1.6×1045

–6– ergs sec?1 . The second model is a power-law with an energy index ?0.75, for which the X-ray luminosity is 7.2±1.4×1044 ergs sec?1 . Reynolds and Fabian (1996) present a detailed deprojection analysis of the cluster X-ray emission from Cygnus A. They assume a cluster core diameter of 300 kpc, and derive a density and pressure in the gas at the core radius of 0.01 cm?3 and 1.4×10?9 dyn cm?2 , respectively, a total gravitational mass of 3×1014 M⊙ , and a total gas mass of 4×1013 M⊙ . For lack of better information we will assume in the analysis below that, if 1138?262 is an X-ray cluster, then the Reynolds and Fabian numbers for Cygnus A are representative of the 1138?262 environment. The X-ray emission from the Cygnus A cluster has a total extent of about 1 Mpc, with about half the emission coming from the high surface brightness cluster core. For 1138?262 the optimum detection cell of 21′′ corresponds to a physical scale of 170 kpc, comparable to the expected cluster core diameter. It may be that, due to cosmological surface brightness dimming, our HRI image of 1138?262 delineates only the higher surface brightness regions, while the low surface brightness emission is lost in the background. In general, cosmological dimming will favor detection of clusters with peaked X-ray surface brightness pro?les at high redshift.

3.

Discussion

Is the X-ray emission from 1138?262 from a hot cluster atmosphere, or from the active galactic nucleus (AGN)? A critical criterion is the spatial extent of the X-ray emission. Unfortunately, given the results on background sources in the ?eld, and the paucity of photons from 1138?262, the current data is inconclusive on this issue. There is much external, circumstantial, evidence for a dense environment for 1138?262. First, the very distorted radio morphology suggests a series of strong jet-cloud collisions

–7– occurring over scales ≈ 100 kpc. Such interaction is supported by optical spectroscopy, showing large velocities, and velocity dispersions, for the line emitting gas in regions associated with the brightest radio knots (Pentericci et al. 1997). Second, the optical morphology consists of many blue knots of emission, with sizes between 5 and 10 kpc, again distributed over ≈ 100 kpc (Pentericci et al. 1998). Pentericci et al. (1997) interpret this distribution as a group of star forming galaxies in the act of merging into a giant elliptical galaxy. This clumpy morphology is also seen for the Ly α emitting gas, and the major axis of the optical line and continuum emission is roughly aligned with that of the radio source. And third, 1138?262 shows the most extreme values of Faraday rotation for any galaxy at z ≥ 2 (Carilli et al. 1997). Observations of lower redshift radio galaxies have shown a correlation between large rotation measures and cluster environment: all sources located at the centers of dense, X-ray emitting cluster atmospheres show large amounts of Faraday rotation (Taylor et al. 1994). An important point is that this correlation is independent of radio source luminosity and morphological class, and hence is most likely a probe of cluster properties, and not radio source properties. The implication is that the hot cluster gas must be substantially magnetized, with ?eld strengths of order a few μG (Carilli et al. 1996). Worrall et al. (1994) have found a correlation between the radio and X-ray emission from the nuclei of luminous, nucleus-dominated, radio loud quasars, from which they conclude that the dominant X-ray emission component is relativistically beamed synchrotron radiation (see also Siebert et al. 1996). The radio nucleus of 1138?262 has a ?ux density at 5 GHz of: S5GHz = 3.7 mJy. Applying the relationship from Worrall et al. then predicts an X-ray ?ux density of: Spredicted = 4×10?4 μJy. The observed value is a factor 40 1keV larger: Sobs = 1.5×10?2 μJy. Worrall et al. also ?nd that many lobe dominated quasars 1keV fall above the nuclear X-ray-to-radio relationship de?ned by the nucleus-dominated quasars (in terms of X-ray ?ux density) by about the same factor as that seen for 1138?262, although the scatter is large. They hypothesize the existence of an extra (unknown) X-ray

–8– emission component in some sources. In the case of 1138?262 we would argue that this excess is likely to be thermal emission from a hot cluster atmosphere. The Worrall et al. relationships apply to broad emission line quasars, while 1138?262 is a narrow emission line galaxy. Perhaps a better comparison is made with the ultra-luminous narrow line radio galaxies Cygnus A and 3C 295, which have radio and X-ray luminosities similar to 1138?262 (P178M Hz ≥ 3x1035 ergs sec?1 Hz?1 , Lx ≈ 1045 ergs sec?1 ). The non-thermal emission from the active nucleus of Cygnus A contributes at most 20% to the total observed X-ray ?ux between 2 keV and 10 keV (Ueno et al. 1994). For 3C 295, the point source contribution to the total observed Einstein HRI ?ux is less than 13% (Henry and Henriksen 1986). A similar result has been obtained for the ultra-luminous radio galaxy 3C 324 at z = 1.2, which has an associated X-ray emitting cluster with size and luminosity similar to 1138?262, with no evidence of an X-ray point source in the ROSAT HRI image (Dickinson 1997). It has been proposed that the increased con?nement of radio lobes provided by a dense local environment may enhance the conversion e?ciency of jet kinetic energy into radio luminosity, thereby leading to a logical association between ultra-luminous radio galaxies and dense cluster atmospheres (Barthel and Arnaud 1996). One complication in the interpretation of 1138?262 which might argue for a signi?cant AGN component is that near infrared imaging of 1138?262 has revealed a bright, small source coincident with the radio nucleus, with K = 16 (Pentericci et al. 1997). This source is two magnitudes brighter than predicted by the Hubble K-z relationship for luminous radio galaxies (McCarthy 1993), perhaps suggesting that 1138?262 is a steep spectrum radio loud quasar in which the optical nucleus is obscured by dust. However, Pentericci et al. (1997) have shown that this K band source can be reasonably ?t with a DeVaucouleur’s law with a scale length of 2′′ (≈ 20 kpc), consistent with a bright elliptical galaxy, and signi?cantly larger than the excellent seeing during the K band observations (seeing FWHM

–9– ≈ 0.6′′ ). Pentericci et al. set a conservative upper limit to the point source contribution in their image of 20%. Unfortunately, their K band image may be contaminated by line emission (Hα and [NII]), which could bias the results depending on the relative distribution of the line and continuum emission. The distorted jet-like morphology of the 1138?262 radio source could also be construed as being more similar to steep spectrum radio loud quasars than to most radio galaxies. Systematically more disturbed morphologies in quasars relative to radio galaxies are thought to arise from a combination of projection (ie. jet axis not far from our line of sight), and relativistic beaming (Barthel and Miley 1988). A counter argument is that 1138?262 does not have a prominent radio nucleus. The nuclear fraction for 1138?262 extrapolated to a rest frame frequency of 2.3 GHz is 0.4% (assuming the core is ?at spectrum below 5 GHz). This fraction is comparable to values seen for luminous narrow line radio galaxies (typically ≈ 0.3%), but is considerably below values seen for broad line radio galaxies (typically ≈ 3%), and steep spectrum radio loud quasars (typically ≈ 50%), although the scatter in the values for each type of source is large (Morganti et al. 1997). Overall, the optical, radio, and X-ray data all favor a hot cluster gas origin for the X-rays from 1138?262, however we cannot preclude an AGN contribution. If the emission is dominated by the AGN, then the extreme rotation measures remain unexplained, and 1138?262 would be very unusual among narrow line radio galaxies in terms of the relative radio and X-ray properties of its nucleus. We proceed under the assumption that the X-ray emission from 1138?262 is from a hot cluster atmosphere at z = 2.156, and we speculate on possible physical implications. First, the over-density at which a structure is thought to separate from the general expansion of the universe, ρsep , and collapse under its own self-gravity is: ρsep =

9π 2 16

× ρbg , where ρbg is

the mean cosmic mass density: ρbg = 7.5×10?29 ×?×(1+z)3 gm cm?3 (Peebles 1993). At a

– 10 – redshift of 2.2 this becomes: ρsep (z=2.2) = 2.5×10?29 ×? gm cm?3 . The density of a typical X-ray cluster is: few×10?29 gm cm?3 ≈ ρsep (z=2.2) for ? = 1 (eg. mass ≈ 1014 M⊙ , size ≈ 1 Mpc). Hence, any large scale structure observed at z ≥ 2 must be dynamically young, having just separated from the general expansion of the universe. Alternatively, massive structures at large redshift might indicate an open universe (? << 1). Second, the existence of a hot cluster-type atmosphere at high redshift would argue for shock heated, primordial in-fall as the origin of the cluster gas, rather than ejecta from cluster galaxies (Sarazin 1986). Such a model would require an early epoch of star formation in order to supply the metals observed in the associated optical nebulosity (Ostriker and Gnedin 1996). Third, the large rotation measures observed raise the question of the origin of cluster magnetic ?elds at early epochs. One possible mechanism is ampli?cation of seed ?elds by a turbulent dynamo operating during the formation process of the cluster as driven by successive accretion events (Loeb and Mao 1994). The timescale for ?eld generation would then be a few times the cluster dynamical timescale, or a few×108 years. Lastly, these observations would then verify the technique of using extreme rotation measure sources as targets for searches for cluster X-ray emission at high redshift. Thus far there have been a total of 11 radio galaxies at z > 2 with source frame rotation measures greater than 1000 rad m?2 , the most distant being at z = 3.8 (Carilli et al. 1997, Ramana et al. 1998, Carilli, Owen, and Harris 1994).

The National Radio Astronomy (NRAO) is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.. D.E.H. acknowledges support from NASA contract NAS 5 30934. We acknowledge support from a programme subsidy provided by the Dutch Organization for Scienti?c Research (NWO).

– 11 – References Barthel, P.D. and Arnaud, K. 1996, M.N.R.A.S. (letters), 283, 45 Barthel, P.D., and Miley, G.K. 1988, Nature, 333, 319 Carilli, C.L., Owen, F., and Harris, D.E. 1994, A.J., 107, 480 Carilli, C.L., R¨ttgering, H.J.A., van Ojik, R., Miley, G.K., and van Breugel, W.J.M. o 1997, Ap.J. (Supp.), 109, 1 Carilli, C.L., Perley, R.A., R¨ttgering, H.J.A., and Miley, G.K. 1997, in IAU o Symposium 175: Extragalactic Radio Sources, eds. C. Fanti and R. Ekers, (Kluwer: Dordrecht), p. 159 Castander, F., Ellis, R., Frenk, C., Dresseler, A., and Gunn, J. 1994, Ap.J. (letters), 424, L79 Crawford, C.S. and Fabian, A.C. 1993, M.N.R.A.S. (letters), 260, L15 Crawford, C.S. and Fabian, A.C. 1995, M.N.R.A.S., 273, 827 Dickinson, Mark 1997, in HST and the High Redshift Universe, eds. N. Tanvir, A. Aragon-Salamanca, and J.V. Wall, (World Scienti?c). Dreher, J.W., Carilli, C.L., and Perley, R.A. 1987, Ap.J., 316, 611 Ebeling, H., Edge, A.C., Fabian, A.C., Allen, S.W., Crawford, C.S., and Bohringer, H. 1997, Ap.J. (letters), 479, L101 Frenk, C.S., White, S.D., Efstathiou, G., and Davis, M. 1990, Ap.J., 351, 101 Henry, J.P. and Henriksen, M.J. 1986, Ap.J., 301, 689 Henry, J.P. 1997, Ap.J. (letters), 489, 1

– 12 – Henry, J.P., Gioia, I.M., Mullis, C.R., Clowe, D.I., Luppino, G.A., Boehringer, H., Briel, U.G., Voges, W., and Huchra, J.P. 1997, A.J., 114, 1293 Loeb, Abraham and Mao, Shude 1994, Ap.J. (letters), 435, L109 Luppino, G.A. and Gioia, I.M. 1995, Ap.J. (letters), 445, L77 McCarthy, P.J., Kapahi, V.K., van Breugel, Wil, Persson, S.E., Ramana, Athreya, and Subrahmanya, C.R. 1996, Ap.J. (supp), 107, 19 McCarthy, P.J. 1993, A.R.A.A., 31, 639 Morganti, R., Oosterloo, T.A., Reynolds, J.E., Tadhunter, C.N., and Migenes, V. 1997, M.N.R.A.S., 284, 541 Nichol, R.C., Holden, B.P., Romer, A.K., Ulmer, M.P., Burke, D.J., and Collins, C.A. 1997, Ap.J., 481, 644 Ostriker, Jeremiah P. and Gnedin, Nickolay Y. 1996, Ap.J. (letters), 472, L63 Oukbir, J. and Blanchard, A. 1997, A&A, 317, 1 Oukbir, J., Bartlett, J.G., and Blanchard, A. 1997, A&A, 320, 365 Peebles, P.J.E. 1983, The Large Scale Structure of the Universe, (Princeton University Press: Princeton) Peebles, P.J.E. 1993, Principles of Physical Cosmology, (Princeton Univ. Press: Princton) Pentericci, L., R¨ttgering, H.J.A., Miley, G.K., Carilli, C.L., and McCarthy, P. 1997, o A&A, 326, 580 Pentericci, L., R¨ttgering, H.J.A., Miley, G.K., and McCarthy, P. 1998, Ap. J. (letters), o submitted

– 13 – Ramana, A., Kapahi, V.K., McCarthy, P., and Subramaniah, R. 1998, Ap.J., submitted. Reynolds, C.S. and Fabian, A.C 1996, M.N.R.A.S., 278, 479 R¨ttgering, H.J.A. 1993, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leiden o Sarazin, Craig L. 1986, Rev. Mod. Phys., 58, 1 Siebert, J., Brinkmann, W., Morganti, R., Tadhunter, C.N., Danziger, I.J., Fosbury, R.A.E., and di Serego Alighieri, S. 1996, M.N.R.A.S., 279, 1331 Stark, A.A., Gammie, C.F., Wilson, R.W., Bally, John, Limke, Richard, Heiles, Carl, and Hurwitz, M. 1992, Ap.J. (Supp.), 79, 77 Taylor, G.B., Ge, J.-P., and Barton, E. 1994, A.J., 107, 1942 Tr¨ mper, J. 1983, Adv. Space Res., 2, 241 u Ueno, Shiro, Koyama, Katsuji, Nishida, Minoru, Shigeo, Yamauchi, and Ward, Martin J. 1994, Ap.J. (letters), 431, L1 Worrall, D.M., Lawrence, C.R., Pearson, T.J., and Readhead, A.C.S. 1994, Ap.J. (letters), 420, L17

– 14 –

Table 1. Source Size Parameters

Source

FWHM arcsec

PA deg

Optimum Cell arcsec

Net Counts

1138-262 5.8′ West 5.9 East 3.8′ Southeast

′

14×9 ± 2 9×7 ± 1 13×6 ± 1 10×6 ± 2

52 ± 11 107 ± 10 143 ± 11 153 ± 15

21 ± 2 15 ± 2 19 ± 2 13 ± 2

31 ± 7 38 ± 7 28 ± 7 16 ± 5

– 15 – Figure Captions Figure 1 – Contours show the Very Large Array radio image of 1138?262 at 5 GHz (Carilli et al. 1997) with a resolution of 0.4′′ ×0.7′′ . The contour levels are a geometric progression in square root two, with the ?rst level being 0.15 mJy beam?1 . The grey-scale shows the optical image (R + B bands) of 1138?262 from the New Technology Telescope (Pentericci et al. 1997). The cross indicates the position of X-ray peak surface brightness, and the cross size indicates the estimated astrometric accuracy. Figure 2 – The X-ray image of 1138?262 from a 41 ksec exposure with the ROSAT HRI. The image has been convolved with a Gaussian beam of FWHM = 10′′ , and a mean background level of 5 counts per beam has been subtracted. The contour levels are: -4, -2, 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 counts per beam. The cross shows the position of the radio and optical nucleus of 1138?262, and the cross size indicates the estimated astrometric accuracy. For the thermal spectral model discussed in section 2, two counts in 41 ksec implies an X-ray ?ux of 1.9x10?15 ergs cm?2 sec?1 in the emitted 2 - 10 keV band, using the Galactic HI column density of 4.5×1020 cm?2 (Stark et al. 1992). Figure 3 – The curves show the mean counts per 1′′ cell in a series of concentric annuli centered on the position of 1138?262 (solid line), and on the positions of the three brightest X-ray sources in the ?eld located within 6′ of 1138?262. All the curves have been normalized to a peak of unity, and the mean background of 0.05 counts per cell has been subtracted. The dotted line is for the source 5.8′ to the west of 1138?262, the short dashed line is for the source 5.9′ to east, and the long dashed line is for the source 3.8′ to the southeast. Each annulus has a width of 3′′ . The error bars are based on photon counting statistics for the target source.

Figure 1

-26 28 55

29 00 DECLINATION (J2000)

05

10

15

20

11 40 49.0

48.5 48.0 RIGHT ASCENSION (J2000)

47.5

Figure 2

-26 28 45

DECLINATION (J2000)

29 00

15

30

11 40 50

49

48 47 RIGHT ASCENSION (J2000)

46

1

0.5

0

0

5

10 Annular Radius

15

20

25

时间计算题汇总

地理时间计算部分专题练习 1、9月10日在全球所占的围共跨经度90°,则时间为:( ) A. 10日2时 B. 11日2时 C. 10日12时 D. 11日12时 3、时间为2008年3月1日的2点,此时与处于同一日期的地区围约占全球的:( ) A. 一半 B. 三分之一 C. 四分之一 D. 五分之一 4、图中两条虚线,一条是晨昏线,另一条两侧大部分地区日期不同,此时地球公转速度较慢。若图中的时间为7日和8日,甲地为( ) A.7日4时 B.8日8时 C.7月8时 D.8月4时 2004年3月22日到4月3日期间,可以看到多年一遇的“五星连珠”天象奇观。其中水星是最难一见的行星,观察者每天只有在日落之后的1 小时才能看到它。图中阴影部分表示黑夜,中心点为极地。回答5—7题 5.图4中①②③④四地,可能看到“五星连珠”现象的是( ) A .① B .② C .③ D .④ 6.在新疆的吐鲁番(约890 E )观看五星连珠现象,应该选择的时间段(时间)是( ) A .18时10分至19时 B .16时10分至17时 C .20时10分至21时 D.21时10分至22时 7.五星连珠中,除了水星外,另外四颗星是( ) A .金星、木星、土星、天狼星 B .金星、火星、木星、海王星 C .火星、木星、土星、天王星 D .金星、火星、土星、木星 (2002年)下表所列的是12月22日甲、乙、丙、丁四地的白昼时间,根据表中数据回答下8-10题。 甲地 乙地 丙地 丁地 白昼长 5∶30 9∶09 11∶25 13∶56 8、四地中属于南半球的是( ) A.甲地 B.乙地 C.丙地 D.丁地 9、四地所处纬度从高到低顺序排列的是( ) A.甲乙丙丁 B.甲乙丁丙 C.丙丁乙甲 D.丁丙乙甲 10、造成四起白昼时间差异的主要因素是( ) ①地球的公转 ②地球自转 ③黄赤交角的存在 ④地方时的不同 A.①② B.②③ C.③④ D.①③ 2002年1月1日,作为欧洲联盟统一货币的欧元正式流通,这将对世界金融的整体格局产生重要影响。回 答4-5题: 11、假定世界各金融市场均在当地时间上午9时开市,下午5时闭市。如果某投资者上午9时在法兰克福(东经8.50 )市场买进欧元,12小时后欧元上涨,投资者想尽快卖出欧元,选择的金融市场应位于:( ) A.东京(东经139.50 ) B.(东经1140 ) C.伦敦 D.纽约(西经740 ) ① ④ ② ③

小学三年级数学《简单的时间计算》教案范文三篇

小学三年级数学《简单的时间计算》教案范文三篇时间计算是继二十四时计时法的学习之后安排的一个内容。下面就是小编给大家带来的小学三年级数学《简单的时间计算》教案范文,欢迎大家阅读! 教学目标: 1、利用已学的24时记时法和生活中对经过时间的感受,探索简单的时间计算方法。 2、在运用不同方法计算时间的过程中,体会简单的时间计算在生活中的应用,建立时间观念,养成珍惜时间的好习惯。 3、进一步培养课外阅读的兴趣和多渠收集信息的能力。 教学重点: 计算经过时间的思路与方法。 教学难点: 计算从几时几十分到几时几十分经过了多少分钟的问题。 教学过程: 一、创设情景,激趣导入 1、谈话:小朋友你们喜欢过星期天吗?老师相信我们的星期天都过得很快乐!明明也有一个愉快的星期天,让我们一起来看看明明的一天,好吗? 2、小黑板出示明明星期天的时间安排。 7:10-7:30 起床、刷牙、洗脸; 7:40-8:20 早锻炼; 8:30-9:00 吃早饭; 9:00-11:00 看书、做作业 …… 3、看了刚才明明星期天的时间安排,你知道了什么?你是怎么知道的?你还想知道什么?

二、自主探究,寻找方法 1、谈话:小明在星期天做了不少的事,那你知道小明做每件事情用了多少时间吗?每 个小组从中选出2件事情计算一下各用了多少时间。 (1)分组学习。 (2) 集体交流。 2、根据学生的提问顺序学习时间的计算。从整时到整时经过时间的计算。 (1)学生尝试练习9:00-11:00明明看书、做作业所用的时间。 (2)交流计算方法:11时-9时=2小时。 3、经过时间是几十分钟的时间计算。 (1)明明从7:40到8:20进行早锻炼用了多少时间呢? 出示线段图。 师:7:00-8:00、8:00-9:00中间各分6格,每格表示10分钟,两个线段下边 的箭头分别指早锻炼开始的时间和结束的时间,线段图涂色部分表示早锻炼的时间。谈话:从图上看一看,从7时40分到8时经过了多少分钟?(20分)从8时到8时20分又经过 了多少时间?所以一共经过了多少分钟。(20+20=40分)小朋友们,如果你每天都坚持锻炼 几十分钟,那你的身体一定会棒棒的。 (2)你还能用别的方法计算出明明早锻炼的时间吗?(7:40-8:40用了一个小时,去掉 多算的20分,就是40分。或者7:20-8:20用了1个小时,去掉多算的20分,就是 40分。) (3)练习:找出明明的一天中做哪些事情也用了几十分钟? 你能用自己喜欢的方法计算出明明做这几件事情用了几十分钟吗?你是怎么算的? 三、综合练习,巩固深化 1、想想做做1:图书室的借书时间。你知道图书室每天的借书时间有多长吗? 学生计算。 (1)学生尝试练习,交流计算方法。 (2)教师板书。 2、想想做做2。 (1)学生独立完成。 (2)全班交流。

古代时间的计算方法

中国古代时间的计算方法(1) 现时每昼夜为二十四小时,在古时则为十二个时辰。当年西方机械钟表传入中国,人们将中西时点,分别称为“大时”和“小时”。随着钟表的普及,人们将“大时”忘淡,而“小时”沿用至今。 古时的时(大时)不以一二三四来算,而用子丑寅卯作标,又分别用鼠牛虎兔等动物作代,以为易记。具体划分如下:子(鼠)时是十一到一点,以十二点为正点;丑(牛)时是一点到三点,以两点为正点;寅(虎)时是三点到五点,以四点为正点;卯(兔)时是五点到七点,以六点为正点;辰(龙)时是七点到九点,以八点为正点;巳(蛇)时是九点到十一点,以十点为正点;午(马)时是十一点到一点,以十二点为正点;未(羊)时是一点到三点,以两点为正点;申(猴)时是三点到五点,以四点为正点;酉(鸡)时是五点到七点,以六点为正点;戌(狗)时是七点到九点,以八点为正点;亥(猪)时是九点到十一点,以十点为正点。 古人说时间,白天与黑夜各不相同,白天说“钟”,黑夜说“更”或“鼓”。又有“晨钟暮鼓”之说,古时城镇多设钟鼓楼,晨起(辰时,今之七点)撞钟报时,所以白天说“几点钟”;暮起(酉时,今之十九点)鼓报时,故夜晚又说是几鼓天。夜晚说时间又有用“更”的,这是由于巡夜人,边巡行边打击梆子,以点数报时。全夜分五个更,第三更是子时,所以又有“三更半夜”之说。 时以下的计量单位为“刻”,一个时辰分作八刻,每刻等于现时的十五分钟。旧小说有“午时三刻开斩”之说,意即,在午时三刻钟(差十五分钟到正午)时开刀问斩,此时阳气最盛,阴气即时消散,此罪大恶极之犯,应该“连鬼都不得做”,以示严惩。阴阳家说的阳气最盛,与现代天文学的说法不同,并非是正午最盛,而是在午时三刻。古代行斩刑是分时辰开斩的,亦即是斩刑有轻重。一般斩刑是正午

excel表格日期计算

竭诚为您提供优质文档/双击可除 excel表格日期计算 篇一:excel中几个时间计算公式 假设b2为生日 =datedif(b2,today(),"y") datediF函数,除excel2000中在帮助文档有描述外,其他版本的excel在帮助文档中都没有说明,并且在所有版本的函数向导中也都找不到此函数。但该函数在电子表格中确实存在,并且用来计算两个日期之间的天数、月数或年数很方便。微软称,提供此函数是为了与lotus1-2-3兼容。 该函数的用法为 “datediF(start_date,end_date,unit)”,其中start_date 为一个日期,它代表时间段内的第一个日期或起始日期。end_date为一个日期,它代表时间段内的最后一个日期或结束日期。unit为所需信息的返回类型。 “y”为时间段中的整年数,“m”为时间段中的整月数,“d”时间段中的天数。“md”为start_date与end_date日期中天数的差,可忽略日期中的月和年。“ym”为start_date 与end_date日期中月数的差,可忽略日期中的日和年。“yd”

为start_date与end_date日期中天数的差,可忽略日期中的年。比如,b2单元格中存放的是出生日期(输入年月日时,用斜线或短横线隔开),在c2单元格中输入 “=datedif(b2,today(),"y")”(c2单元格的格式为常规),按回车键后,c2单元格中的数值就是计算后的年龄。此函数在计算时,只有在两日期相差满12个月,才算为一年,假如生日是20xx年2月27日,今天是20xx年2月28日,用此函数计算的年龄则为0岁,这样算出的年龄其实是最公平的。 身份证号提取年龄 =datediF(--text((len(a1)=15)*19”即可获得当时的日期时间; 2、使用公式:用=now()而非=date(),=date()只有日期,然后进行菜单“工具->选项”,选择“重新计算”页,选中“人工重算”,勾不勾选“保存前自动重算”看自己的需要和想法了,如果勾选了,那日期时间那总是最后一次保存的日期时间,不勾选的话,如果你的表格中有公式记得准备存前按F9 篇二:excel中如何计算两个日期之间的月数 excel中如何计算两个日期之间的月数

时间计算公式

高中地理计算公式 一、时间的计算 1、求时区: 时区数=已知经度/15°(商四舍五入取整数,即为时区数) 2、求区时: 所求区时=已知区时±时区差(东加西减) 3、求地方时: 所求地方时=已知地方时±4分钟/度×经度差(东加西减) 二、太阳高度的计算 1、求正午太阳高度: H=90°-︱纬度差︱(纬度差指当地纬度与太阳直射纬度之间的差) 2、求子夜太阳高度: H=︱纬度和︱-90°(纬度和指当地纬度与太阳直射纬度之间的和) 3、求南北两楼的楼间距: L=h?cotH (h为楼高,H为该地一年中最小的正午太阳高度) 三、昼夜长短的计算 1、求昼长: (1)昼长=昼弧∕15° (2)昼长=日落时间-日出时间 (3)昼长=24-夜长 (4)昼长=(12-日出地方时)×2 (5)昼长=(日落地方时-12) 2、求夜长 (1)夜长=夜弧∕15° (2)夜长=24-昼长 (3)夜长=(24-日落地方时)×2 (4)北半球某纬度的夜长=南半球同纬度的昼长 四、日出、日落时刻的计算 1、求日出时刻: (1)日出时刻=当地纬线与晨线交点的时刻(2)日出时刻=12-昼长∕2 2、求日落时刻: (1)日落时刻=当地纬线与昏线交点的时刻(2)日落时刻=12+昼长∕2 五、球面距离的计算 (1)赤道和经线上的距离111Km×度数 (2)纬线上的距离=111Km×度数?COSθ(θ为当地的纬度) (3)对趾点的计算:经度互补,一东一西;纬度相等,一南一北。 六、比例尺的计算 (1)比例尺=图上距离∕实地距离 (2)缩放图幅面积=原图幅面积×比例尺缩放的平方 七、相对高度的计算 (1)陡崖相对高度:(n-1)d≤H<(n+1)d (n为等高线条数,d为等高距) (2)H=T∕6°×1000米 (H为两地相对高度,T为两地温差)

日期计算器

程序设计与算法课程设计

课程设计评语 对课程设计的评语: 平时成绩:课程设计成绩: 总成绩:评阅人签名: 注:1、无评阅人签名成绩无效; 2、必须用钢笔或圆珠笔批阅,用铅笔阅卷无效; 3、如有平时成绩,必须在上面评分表中标出,并计算入总成绩。

目录 课程设计评语 (2) 目录 (3) 1.课程论文题目.............................................................................................. 错误!未定义书签。2.程序设计思路.. (4) 3.功能模块图 (4) 4.数据结构设计 (5) 5.算法设计 (5) 6.程序代码 (6) 7.程序运行结果 (7) 8.编程中遇到的困难及解决方法.................................................................. 错误!未定义书签。9.总结及建议.................................................................................................. 错误!未定义书签。10.致谢. (8)

1.课程设计题目:日期计算器 【要求】 功能:计算输入日期是当年中的第几天 系统要求实现以下功能: 1. 由用户分别输入:年、月、日 2. 计算该日期是当年中的第几天 3. 输出计算出的天数 分步实施: 1、首先设计Dater对象构造器 2、判断此年是否为闰年。 3、计算从此年年初到此日的一共多少天 4、输入输出处理。 【提示】 需求分析:使用Dater对象构造器,用1判断为闰年,,0判断为不是闰年,使用累加的方法计算年初到此日共有多少天,进行输入输出处理. (1)主函数设计 主函数提供输入,处理,输出部分的函数调用。 (2)功能模块设计 模块:由用户自己录入年,月,日,、。计算该日期为一年的中德第几天。输出计算出的天数,返回主菜单。 3. 功能模块图 (1)输入模块 由用户分别输入:年、月、日

最新小学二年级钟表题时间计算题(经过时间计算)

精品好文档,推荐学习交流

二年级认识钟表练习----填经过时间

(

)

(

)

二年

班 姓名:

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

综合病例(过敏性休克)----场景一

仅供学习与交流,如有侵权请联系网站删除 谢谢1

(

)

(

)

精品好文档,推荐学习交流

题干内容

模拟病人设置

护理能力(考点)

(主动提供给选手)

(选手有询问或有操作责提 (本栏题干给评委)

供,反之则不提供)

1 床,李明,男,76 岁,体 1.病人:诉 5 分钟前做了青霉 1.评估:快速评估病人具体不

重 60KG,有中风病史 3 年,3 素皮试后,现全身皮肤瘙痒, 适,查看皮试的位置

天前因喂食发生呛咳后出现 头晕、胸闷、气促、呼吸困难 2.判断:口述病人可能出现过

发热、咳嗽、咳痰而入院, 伴濒死感。半卧位

敏性休克,需要立即抢救。

入院第二天,病人突然诉说 2.特殊用物准备:备皮试抢救 3.处理:

全身皮肤瘙痒,头晕、胸闷、 盒在床边

①呼救医生(特别考点)医生

气促、呼吸困难伴濒死感

3.家属:护士,我家人怎么 回复正在抢救另一个病人,尽

考核:病人可能发现什么情 了?为什么会这样?

快到达,考察选手抢救状态

况?你该如何处理

4.医生:呼救医生时,医生回 下,医生未到时的临床思维,

备注:开始 7 分钟,出现第 复正在抢救另一病人会尽快 继续操作得分,等待医生后操

二场景

过来

作扣分。

5.工作人员:第 7 分钟给选手 ②选手与家属有效沟通,人文

第二场景

关怀

③摆放平卧体位

④医生未到之前抽吸肾上腺

素 1 支 1mg(特别考点)指

出准备的剂量有错

⑤吸氧(中流量吸氧)

⑥心电监护(特别考点)因右

侧肢体瘫痪,原则上不用右侧

肢体绑袖带

场景二 题干内容 (主动提供给选手)

医生到达,口头医嘱肾上腺 素 1mg 皮下注射 考核要求:请执行医嘱并给 予相应的处理 备注:开始 9 分钟,出现第 三场景

模拟病人设置

护理能力(考点)

(选手有询问或有操作责提 (本栏题干给评委)

供,反之则不提供)

1.工作人员:选手上心电监护 4.向医生汇报病人情况

后提供:

5.肾上腺素 1mg 皮下注射

心电监护显示:HR130 次/分, R:28 次/分 BP:75/55mmHg, sop2:90% 2.工作人员:第 9 分钟给选手 第三场景

仅供学习与交流,如有侵权请联系网站删除 谢谢2