Trade in educational services trends and emerging issues

Trade in Educational Services:Trends and Emerging Issues Kurt Larsen,John P.Martin and Rosemary Morris

1.INTRODUCTION

U NTIL recently,education has been largely absent from the debate on globalisation because it was thought to be essentially a non-traded service.But this is not the case.Traded educational services are already a major business in some countries,e.g.in Australia,Canada,New Zealand,the United Kingdom and the United States.The largest component of international trade in educational services is accounted for by students travelling to study abroad.This trade has been established over many years,but a newer prospect is the widespread provision of courses and qualifications by providers originating from,and in some cases operating,outside the country of a student who stays at home.New communication possibilities such as the Internet are creating rapidly the conditions that could allow such trade to flourish in the future.

In recognition of these facts,educational services are already covered under the present GATS commitments undertaken both during the Uruguay Round and afterwards by 38WTO Members (counting as one the 1994schedule of 12EU member states),and represent one sector for which three negotiating proposals have been received (at the time of writing).

This paper seeks to further the international debate on trade in educational services by summarising what is known about it and what are some of the main policy issues arising from such trade.It addresses the following issues:q What is known about the size of,and trends in,the international market in educational services (Section 2)?

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd 2002,108Cowley Road,Oxford OX41JF,UK and 350Main Street,Malden,MA 02148,USA.849

KURT LARSEN and JOHN P.MARTIN are respectively attached to the OECD’s Centre for Education Research and Innovation and its Directorate for Education,Employment,Labour and Social Affairs;ROSEMARY MORRIS is currently attached to the OECD’s Directorate for Financial,Fiscal and Enterprise Affairs but was attached to the Trade Directorate when the paper was written.The authors are grateful to Dermot McAleese and an anonymous referee for helpful comments on an earlier version of the paper,and to Jocelyne Carvallo and Aline Renert for secretarial assistance.The views expressed are the authors’own and cannot be held to be those of the OECD or its Member governments.

850KURT LARSEN,JOHN P.MARTIN AND ROSEMARY MORRIS q What are the implications of the on-going GATS negotiations for further trade liberalisation in this sector(Section3)?

q What are the major policy challenges posed by trade in educational services (Section4)?

2.LEVELS AND TRENDS IN TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES

Existing data about the level and content of trade in educational services are scarce and difficult to evaluate.This paper uses existing data from the OECD data base on International Trade in Services and from the OECD Indicators for Education Systems(INES)data base on foreign students in tertiary education to give an overview of the approximate scale of this trade.It also highlights the problems with existing data sources,which hinder efforts to get a reliable picture of the size of international trade in educational services.This section is divided into three parts:(a)methods of compiling the statistics;(b)main trends in trade in educational services;and(c)a rough estimate of the size of trade in educational services in OECD countries.

a.Methods of Compiling the Statistics

(i)Trade in services statistics1

Statistics on trade in educational services are classified under several headings and are often lumped together with other activities.It is therefore not easy,and sometimes impossible,to identify‘trade in educational services’using standard statistics on services trade.The trade data used in this paper were collected according to the OECD/Eurostat classification.In this classification,‘trade in educational services’is counted under the following headings:

1.242Personal travel,Education-related expenditure;

2.936Miscellaneous business,professional and technical services.Other.

The first category mentioned above consists of educational services where individual students pay a tuition fee to education institutions and/or living costs when studying abroad.This corresponds to mode2(consumption abroad)in the WTO classification of different modes of supplying goods and services across borders(see Box1).Estimates of foreign students’expenditures in the country are made by multiplying the number of such students(which is known with some precision)by an estimate of average expenditures per student.Receipts consist largely of expenditures for tuition and living expenses for foreign students enrolled in a country’s universities and colleges–these are treated as service 1See OECD(2001b)for further details.

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES:TRENDS AND ISSUES851

BOX1

The Different Modes of Services Trade According to the GATS Classification

‘exports’from the perspective of the country in which the student is studying. Payments consist of tuition and living expenses of students who study abroad–these are treated as service‘imports’from the perspective of the country of origin of the student in question.

The second category mentioned above includes trade in educational and training services when the services are provided on a contract or fee.It corresponds to mode1(cross-border supply)in the WTO classification.This category includes,for example,employee training or educational testing services provided by a foreign company or institution.It also contains the service provided by a manufacturer where the foreign customer buys training services as part of the delivery,maintenance or installation of a good or service.And finally,it contains cross-border e-learning activities provided by companies and educational institutions.Unfortunately,it is not possible in the OECD data base to separate trade in educational services from a number of other services included in‘936Miscellaneous business,professional and technical services.Other’.

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

852KURT LARSEN,JOHN P.MARTIN AND ROSEMARY MORRIS With current international trade statistics it is not possible to identify separately the earnings from universities,other educational institutions and companies engaged in providing training services which are all present in another country (offshore activities).Data on sales by these‘foreign affiliates’are not included in international trade statistics in line with current international rules for collecting trade data.Only their earnings are recorded in the accounts as international transactions,and here they appear as‘income’rather than‘services’.This category corresponds to mode3(commercial presence)in the WTO classification.

It should also be noted that trade according to mode4(Presence of natural persons–an individual entering another country to provide an educational service)in the WTO classification is not accounted for in services trade statistics unless the earnings from this activity are transmitted to another country.These earnings are covered in trade statistics under‘compensation of employees’,e.g. the earnings of teachers and other education professionals who work abroad for less than one year.

(ii)Statistics on foreign students in tertiary education

The OECD INES statistics on foreign students in tertiary education are based on data compiled by the host country,and therefore relate to incoming foreign students to a particular country,rather than to students from that country going abroad.Foreign students are usually identified on the basis of citizenship or,in some cases,by an alternative criterion(e.g.nationality,place of birth,former domicile).The application of this criterion thus generates a bias,related to the differences between host countries’policies on obtaining nationality.Indeed, children of non-naturalised migrants may have been living in the host country for a long time(some are born there)which does not,a priori,justify attaching them to their country of origin or that of their parents to measure the proportion of students going abroad for their education(OECD,2001a).2

Students studying in countries which did not report to the OECD are not included in the statistics.As a consequence,the INES data on students abroad underestimate the total numbers of foreign students in OECD countries.In the 1998statistics on foreign students in tertiary education,there are no data for the following OECD countries:Belgium(French Community),Greece,Mexico,the Netherlands and Portugal.In the1999statistics,only data from Greece and Portugal are missing.

2To take one example,Germany is a popular destination for foreign students studying in the OECD countries,but the actual number of non-resident students(or students who attended upper secondary education in another country)registered in German higher education institutions accounts for only two-thirds of all foreign students.This is because of the presence of a significant number of‘domestic foreigners’,consisting mainly of children of‘guest workers’who,despite having grown up in Germany,are considered‘foreign’in these statistics.A quarter of all foreign students in Germany have ethnic origins in Greece,Italy and Turkey(OECD,2000b).

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES:TRENDS AND ISSUES853

b.Trends in Trade in Educational Services

(i)Using trade in services statistics

In the OECD data base on international trade in services statistics,seven countries have reported data on‘Personal travel,education-related activities’: Australia,Canada,Mexico,New Zealand,Poland,the United Kingdom and the United States.These countries include four major‘exporters’of trade in educational services,namely Australia,Canada,the United Kingdom and the United States.Tables1to5show data on educational services for these seven countries,measured as the receipts or payments of foreign students studying abroad corresponding to the category.

As mentioned above,these data correspond only to mode2(consumption abroad).Nevertheless,the largest share of cross-border trade in educational services occurs through the travel of students to study at foreign institutions,and this indicator is therefore often used to estimate the overall level of trade in educational services.As noted below,this estimate is likely to become less and less accurate in the future as other forms of trade in educational services(e.g. e-learning and corporate training)are growing rapidly.

Table1shows that the United States is by far the biggest‘exporter’of edu-cational services among the seven countries,followed by the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada.Australia has,over the period1970–99,experienced a very high growth in the trade of educational services.As a result,education has become Australia’s eighth largest export industry,corresponding to12per cent of total Australian exports of services(Table2).In contrast,Canada has experienced a relatively lower growth in its trade in educational services than Australia,the United Kingdom and the United States.As a result,the relative importance of Canadian exports of educational services as a percentage of total services exports has fallen from three per cent in1989to two per cent in1999(Table2).

TABLE1

Exports of‘Personal Travel,Education-related Activities’,1970–1999

(US$million)

19701989199719981999 Australia6584219018442030 Canada68530595621703 Mexico (444947)

New Zealand (282211209)

Poland....1626.. United Kingdom..221440804464.. United States..4575834690379572 Note:

..not available.

Source:OECD statistics on trade in services.

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

854KURT LARSEN,JOHN P.MARTIN AND ROSEMARY MORRIS

TABLE2

Exports of‘Personal Travel,Educational-related Activities’as a Percentage of Total Trade in

Services,1970–1999

19701989199719981999 Australia0.6 6.611.811.411.6 Canada 2.7 3.0 1.9 1.9 2.0 Mexico....0.50.40.4 New Zealand.... 6.6 5.7 4.9 Poland....0.20.2.. United Kingdom.. 4.5 4.3 4.5.. United States.. 4.4 3.5 3.7 3.8 Note:

..not available.

Source:OECD statistics on trade in services.

However,these data clearly underestimate the current levels of trade in educational services.They do not include the educational services included in ‘936Miscellaneous business,professional and technical services.Other’.Nor do the tables include the earnings from affiliated companies and institutions in educational services.It is likely that the size of the underestimate has increased over time.

On the other hand,other transactions in the current account partly offset the receipts shown in Tables1and2.Surveys of foreign students in the United States,for example,indicate that roughly three-quarters of their education are financed from sources abroad.The remainder,however,is financed from sources within the United States–through scholarships from colleges,universities, private corporations or other non-profit institutions.These payments to foreigners are included in private remittances and other transfers in the trade statistics(US Department for Commerce,2000).

Table3shows data on‘imports’of educational services,i.e.payments made for students studying abroad.Once again,the United States is the largest importer,followed by Canada and Australia(there are no import data for New Zealand).But Table4–which expresses imports as a percentage of total services imports–shows that Australia and Canada are the largest importers by this https://www.360docs.net/doc/1051891.html,paring Tables1and3,it is clear that Australia,Canada,the United Kingdom and the United States have a‘trade surplus’in educational services. However,using Tables2and4,one can compute an indicator of countries’‘revealed comparative advantage’in trading educational services,defined as exports minus imports as a proportion of total services trade.By this measure, Australia appears to be the most competitive exporter in this market followed by New Zealand,the United Kingdom and the United States in that order(see Table 5).

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES:TRENDS AND ISSUES855

TABLE3

Imports of‘Personal Travel,Education-related Activities’,1970–1999

(US$million)

19701989199719981999 Australia24178410337378 Canada37258532523563 Mexico (444947)

Poland....4148.. United Kingdom..67182217.. United States..586139615911840 Note:

..not available.

Source:OECD statistics on trade in services.

TABLE4

Imports of‘Personal Travel,Education-related Activities’as a Percentage of Total Trade in

Services,1970–1999

19701989199719981999 Australia 1.5 1.3 2.2 2.0 2.1 Canada 1.1 1.1 1.4 1.4 1.4 Mexico....0.30.40.3 Poland....0.70.7.. United Kingdom..0.20.20.3.. United States..0.70.90.9 1.1 Note:

..not available.

Source:OECD statistics on trade in services.

TABLE5

Revealed Comparative Advantage in‘Personal Travel,Education-related Activities’,1970–1999 (Exports minus Imports as a percentage of total services trade)

19701989199719981999 Australiaà0.9 5.39.69.49.5 Canada 1.6 1.90.50.50.6 Mexico....à0.20à0.1 Poland....à0.5à0.5.. United Kingdom.. 4.3 4.1 4.2.. United States.. 3.7 2.6 2.8 2.7 Note:

..not available.

Source:OECD statistics on trade in services.

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

856KURT LARSEN,JOHN P.MARTIN AND ROSEMARY MORRIS

There exist only scattered data on trade in educational services under modes1,3 and4.From US trade statistics,it is,however,possible to get more information on mode1trade(cross-border supply)in educational https://www.360docs.net/doc/1051891.html, data on services trade include a category entitled‘training services’which includes sales of,e.g., employee training or educational testing by a US company or institution abroad. The total amount of this activity is relatively small(only US$408million in exports and US$175million in imports in1999)compared with the category242(US Department of Commerce,2000).3

With the development of electronic commerce and a corresponding expansion of distance learning as suppliers make use of new and enhanced information and communication technologies,the potential of pure cross-border trade in educational services(mode1),traditionally associated with modes2and3,is becoming more significant.4

Cross-border e-learning activities are likely growing at a faster rate than the number of students studying abroad,although from a low level.Increasingly, educational institutions,publishers and ICT companies are teaming up to design and deliver e-learning courses on a variety of https://www.360docs.net/doc/1051891.html,rge companies are also developing education and training courses to improve the skills of their employees and to keep these up to date.Again,there is very little information on the scale of these activities and the proportion that is traded cross-border.It is estimated that there were6,250foreign‘distance-learning’students at Australian universities in the beginning of2000,corresponding to six per cent of all the foreign students enrolled at Australian universities.

There are few statistics available on mode3trade.According to a study by the Australian Vice-Chancellors’Committee in May1999,35Australian universities reported750offshore programmes with31,850students.The vast bulk of such pro-grammes were concentrated in four countries:Singapore,Hong Kong,Malaysia and China(IDP Education Australia,2000).Another estimate is that75per cent of UK universities had at least one overseas validated course in1996/97,corresponding to around135–140,000students during the1996/97academic year(Bennell and Pearce, 1998).Investment or establishment-related trade in education(mode3)is also likely to grow in the future,as universities and other higher education institutions increasingly seek to establish campuses and teaching facilities abroad.5

3However,US services trade statistics do not permit one to isolate trade in educational services when it is either provided to a company or institution abroad as part of a delivery,maintenance or installation of a good or as an e-learning activity(mode1).

4E.g.Duke University in the United States offers a‘Cross-Continent’MBA programme that has a large on-line tuition component,allowing enrolment and participation of foreign students without requiring them to move to the United States.‘Internet-mediated learning’is combined with residential learning sessions in a number of the university’s facilities established abroad.

5In Australia,for example,over a third of new overseas enrolments in1999were accounted for by enrolments in offshore facilities(Australian Education International,Overseas Students Statistics 1999,2000;see https://www.360docs.net/doc/1051891.html,.au for extracts).

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

(ii)Statistics on foreign students in tertiary education

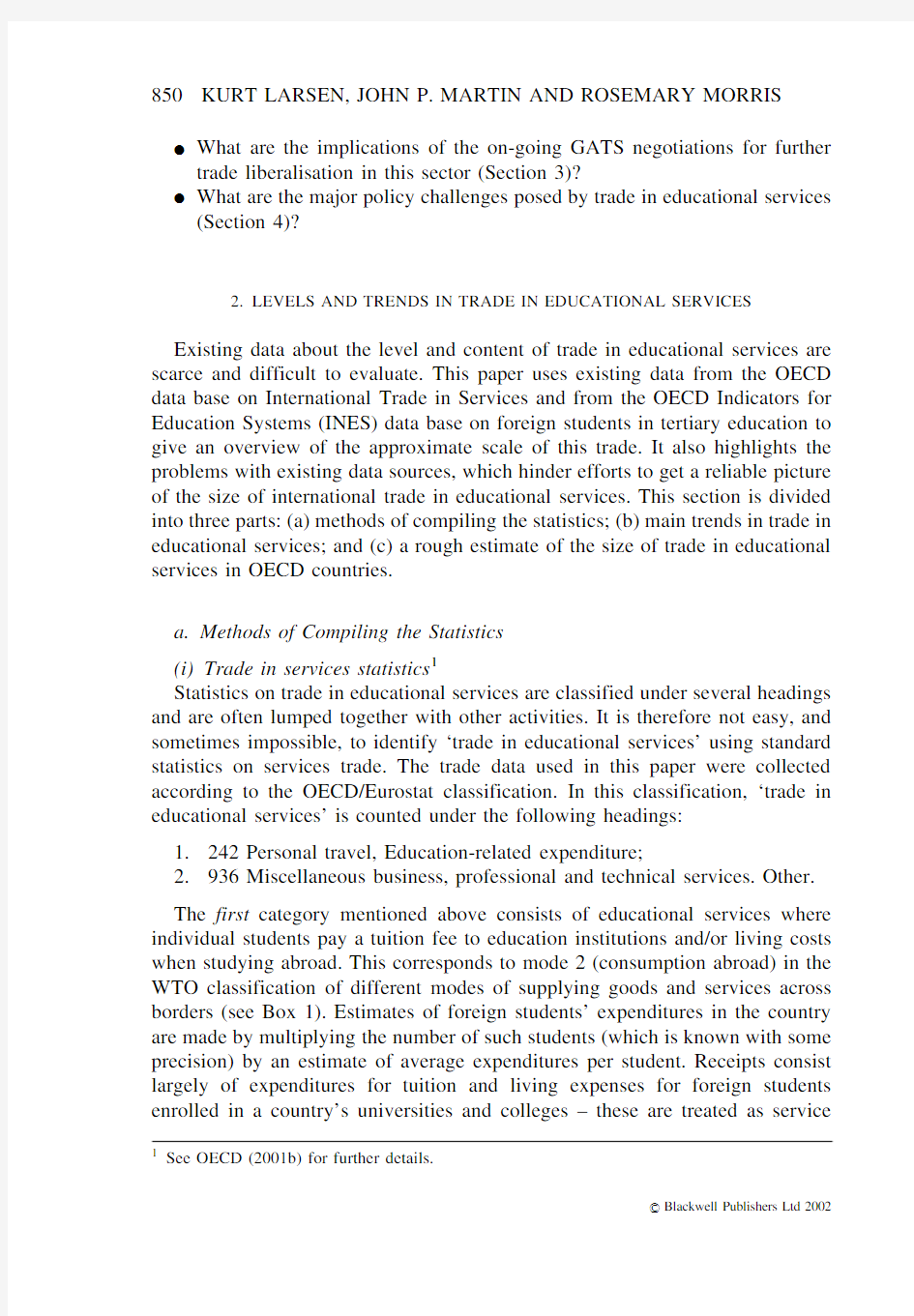

Figure 1shows that the United States is the most popular destination for foreign students (in terms of the absolute number of foreign students)with 31per cent of the total,followed by the United Kingdom (16per cent),Germany and France (12and 9per cent,respectively)and Australia (8per cent).Five countries (Australia,France,Germany,the United Kingdom and the United States)thus attract more than 75per cent of all foreign students studying in the OECD area.By way of comparison,these five countries accounted for 44and 47per cent of the total OECD population and labour force,respectively.

The main countries of origin of these foreign students are often non-OECD countries (see below),but 43per cent were from OECD countries in 1998.A breakdown of foreign students by region of origin allows the predominant flows to be identified,in particular in Australia,where some 75per cent of foreign students come from the Asia-Pacific region.There are major student flows between Africa and France (over 40per cent of entries),between the Asia-Pacific on the one hand and the United States on the other (two-thirds of entries).Among OECD countries that mainly admit students from other OECD countries,Switzerland and Austria take in mainly Europeans,while Germany and the United Kingdom take in large numbers of students from Asia and the Pacific (one-third of entries)besides a large contingent of European

students.FIGURE 1

Distribution of Foreign Students in OECD Countries by Host Country,1999

Source:OECD Education Database.

TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES:TRENDS AND ISSUES 857

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd 2002

858KURT LARSEN,JOHN P.MARTIN AND ROSEMARY MORRIS Among all foreign students studying in OECD countries in1998,Greek, Japanese and Korean students comprise the largest proportion of students from other OECD countries,each representing about four to five per cent of all foreign students,followed by Germans,Turks,French and Italians.Together,these countries account for about25per cent of all foreign students in OECD countries. China(including Hong Kong)accounts for almost nine per cent of all foreign students studying in OECD countries,followed by Malaysia(four per cent)and India(three per cent).Other Southeast Asian countries are also very active in sending students to OECD countries:five per cent of all foreign students originate from Indonesia,Singapore and Thailand(OECD,2000b).

The OECD has also recently collected statistics on foreign students in tertiary education in1999.There has been an increase in the number of foreign students enrolled in tertiary education in OECD countries from1.31million in1998to

1.42million in1999.6

c.A Rough Estimate of OECD Trade in Educational Services

Combining the statistics on trade in services and on foreign students in tertiary education,we have relatively good information on mode2trade in educational services(consumption abroad)in OECD countries.Approximately1.47million foreign students in tertiary education were studying abroad in OECD countries in 1999.The average expenditure per year of students studying in the seven countries shown in Table1above is US$20,600(including fee payments and living expenditures).Given that these seven countries attract over57per cent of all foreign students studying in OECD countries,it seems reasonable to assume that this estimate of average spending per student is a good proxy for the OECD average.This suggests that the overall market in OECD of mode2trade in educational services is around US$30billion in1999,corresponding roughly to three per cent of total trade in services in OECD countries.7

This figure is a rough estimate since the number of1.47million foreign students refers only to students in tertiary education.Students in vocational education and training or in primary and secondary education are not included in this figure.For example,across all sectors of education–higher education, vocational education and training,schools and English-language courses–Australia was host in1999to158,000foreign students,whereas the total number of foreign students in tertiary education in the same year was117,500.The figure of US$30billion is therefore an underestimate of the total OECD market in 6The1999figure does not include data from Belgium,Mexico and the Netherlands,for whom 1998data were not available.If these countries are included,the total number of foreign students enrolled in tertiary education in1999in OECD countries is1.47million.

7According to WTO(2000),total OECD exports of services amounted to around US$1,120 billions in1999.

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES:TRENDS AND ISSUES859 educational services.On the other hand,the average costs for students studying in continental Europe are typically somewhat lower than US$20,600as student fees are typically non-existent or low.The living expenditures of students studying abroad in Europe are,however,accounted for in services trade statistics under ‘242Personal travel:education-related expenditure’.

3.THE IMPLICATIONS OF GATS FOR TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES

The GATS is a multilateral,legally enforceable agreement governing international trade in services.It offers for services trade the same stability that arises from mutually agreed rules and binding market access and non-discriminatory commitments that the GATT has provided for goods trade for more than five decades.The GATS forms part of the Uruguay Round single undertaking‘package’of multilateral agreements,so all WTO Members are bound by GATS rules.The coverage of the GATS is extremely wide:all service sectors are covered with the exception of‘services supplied in the exercise of governmental authority’.

The GATS consists of three core components:the framework of rules that lays out general obligations(e.g.transparency,most-favoured-nation(MFN) treatment),annexes on specific sectors(telecommunications,financial services, etc.),and the schedules of commitments submitted by each Member country, detailing the Member’s liberalisation undertakings by sector.

a.Current Commitments under the GATS

Education services are covered under chapter5of the GATS classification system.Its sub-division into five sub-sectors–(A)primary,(B)secondary,(C) higher,(D)adult and(E)other8–reflects traditional education structures. Education,together with the energy sector,remains one of the sectors where WTO Members have been least inclined to schedule liberalisation commitments. To date,only38Members(counting as one the1994schedule of the then12EC member states)have made commitments for at least one education sub-sector.

Given that national policy objectives often involve specific service sectors,the GATS was designed to allow countries to tailor their commitments to suit those objectives.WTO Members are free,for example,to leave entire sectors out of their GATS commitments,or they may choose to grant market access in specific sectors,subject to the limitations they wish to maintain.Market access and 8The definition of the‘other sector’is:education services at the first and second levels in specific subject matters not elsewhere classified,and all other education services that are not definable by level.

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

860KURT LARSEN,JOHN P.MARTIN AND ROSEMARY MORRIS national treatment obligations apply only to the sectors in which a country chooses to make commitments.General obligations,however,such as those relating to transparency,apply to all services covered by the GATS,regardless of whether liberalisation commitments have been scheduled or not.Through negotiating‘rounds’,countries choose the sectors and modes of services trade they wish to include in their schedules,as well as the limitations on market access and national treatment they wish to maintain(AUCC,2001).It is only by reference to the individual country schedules that one can know the degree to which service sectors have actually been opened.

A survey of market access commitments in education services under GATS reveals the following:19of the38Member countries have included commitments for at least four of the five education sectors.9Thus,the number of schedules containing commitments on the different education sectors is relatively constant:27on primary education,31on secondary education,29on higher education and27on adult education.The least frequently committed sector is‘Other education’,for which commitments were made by only17 member countries.It should be noted that,among OECD countries,two-thirds of them have made commitments in four out of five education sectors.Only five OECD countries have made no commitments in educational services.

Regarding cross-border supply(mode1),primary and secondary education have been fully committed(no limitations)in slightly more than half of the schedules.10The corresponding share for‘higher education’and‘adult education’is higher,where approximately three-quarters of all existing commitments are without limitations.11

Limitations on the consumption abroad of education services(mode2)are very rare in all education sub-sectors.As in many other services areas,countries see less need–or scope–for restricting trade under this than any other mode of supply,given that the consumption of the service takes place outside their national boundaries.12

Regarding commercial presence(mode3),primary,secondary and higher education have‘no limitations’in about half of the schedules.13In‘Adult education’,18of27members have‘no commitments’.

Finally,regarding presence of natural persons(mode4),almost every country has scheduled‘unbound’for all education sub-sectors,implying that no commitments in those sectors have been taken.

9These members are:Albania,Czech Republic,Estonia,European Union,Georgia,Hungary, Japan,Jordan,Kyrgyz Republic,Lesotho,Liechtenstein,Lithuania,Mexico,Norway,Oman, Poland,Sierra Leone,Slovak Republic and Switzerland.

10Primary:15of27;Secondary:20of32.

11Higher education:21of29;Adult:22of27.

12No limitations:Primary:25of27;Secondary:30of32;Higher:25of29;Adult:26of27. 13Primary:13of27;Secondary:17of32;Higher:15of29.

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES:TRENDS AND ISSUES861 The schedules of those Members who acceded to the WTO after the Uruguay Round generally contain more ambitious market access commitments,with a wider sectoral coverage.This is perhaps due in part to the difference in negotiating contexts between an accession and a normal trade round.14It should also be noted that,while many acceding Members have taken liberal market access commitments for primary and secondary education services,the majority of them(as well as some of the original GATS signatories)make it clear that their commitments apply only to privately-funded education services.

In sum,WTO Member countries have chosen to impose considerably more limitations on trade in educational services in modes3and4than in modes1and 2.This is also the common picture for trade in other services.Furthermore, Member countries have in general put slightly more limitations on trade in primary and secondary education(considered as‘basic’schooling in many OECD countries)than on higher and adult education.

b.Issues in the On-going GATS Negotiations

The primary goal of the Uruguay Round in the services field was to establish the legal framework through which liberalisation would be achieved in successive negotiating rounds;little real liberalisation was secured at that time,as most Members made commitments that bound the status quo,with generally limited sectoral coverage.Negotiations under the GATS resumed formally on1January, 2000,in accordance with the Agreement’s so-called‘built-in agenda’,i.e.its provision for:

successive rounds of negotiations,beginning not later than five years from the date of entry into force of the WTO Agreement and periodically thereafter,with a view to achieving a progressively higher level of liberalisation(GATS,Article XIX).

Therefore,with each round,Members are expected to negotiate to continue the process of progressive liberalisation of services trade,by both broadening and deepening their liberalisation commitments.

Negotiations are taking place via the WTO Council of Trade in Services,with a review of progress in the negotiations scheduled for March2002.All service sectors,including education,may be covered by the negotiations.Over70 negotiating proposals covering a wide range of sectors have already been submitted by more than40Members.The following sub-section addresses two topics:(i)criticisms relating to liberalisation of trade in education services put forward by some commentators and NGOs;and(ii)the three negotiating proposals for further multilateral liberalisation of trade in educational services put forward recently by Australia,New Zealand and the United States.

14See WTO(2001).

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

862KURT LARSEN,JOHN P.MARTIN AND ROSEMARY MORRIS

(i)Education services trade and GATS critics

Education,along with health and other social services,is a politically sensitive sector for multilateral trade negotiations.Almost all countries view education,at least up to a certain age,as an essential social service and provide publicly-funded education on a compulsory and universal basis.There are,however, significant variations between countries’education systems concerning the level of public funding and public delivery of education and the degree to which private education is available;mixed systems,allowing the choice between public and private schooling,are common.

Among the principal NGO concerns about liberalisation of trade in education services,two are highlighted here:

q That the co-existence of public and private services calls into question the status of public services as government services excluded from the scope of the GATS.

GATS Article I(3)(b)provides that the Agreement applies to‘any service in any sector except services supplied in the exercise of governmental authority’. I(3)(c)provides that‘any service which is supplied neither on a commercial basis,nor in competition with one or more service suppliers’is such a service.It is often asserted that,in mixed education systems,the private sector‘competes’with the public sector,thus bringing government-supplied services into the GATS arena.Co-existence of public and private providers is common in social services such as health and education.But such co-existence does not necessarily mean that they are‘like services’,nor that they are in competition,and therefore does not bring public services automatically into the purview of the GATS.Nor does the fact that fees might be charged for some governmental services,e.g.for school enrolments,automatically make the service one supplied‘on a commercial basis’.

Even so,a clarification of this article by GATS members could help alleviate fears that government-supplied social services are under threat as a result of participation in the GATS.In this connection,one informed observer has suggested that a means of clarifying the non-commercial basis element could be to equate it with the idea of a‘not-for-profit basis’.15The WTO Secretariat has recently noted that,given the attention accorded to the‘public services carve-out’clause in the media,the new round provides a good opportunity to: make it clear that the co-existence of governmental and private services in the same industry does not mean that they are in competition in the sense of Article I.3(c)and therefore does not invalidate the exclusion from the GATS of the public sector(WTO,2001,p.124).

q That the GATS threatens Governments’sovereign rights to regulate and pursue social policy objectives.

15See Hartridge(2000).

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES:TRENDS AND ISSUES863 This concern does not take into account the fact that the rights of Governments to regulate in order to meet national policy objectives are recognised explicitly in the preamble to the Agreement.16It also ignores the flexibility of the GATS,in that Members retain full freedom to choose not only the sectors and modes of supply for which they want to make market-access commitments,but also to determine the content of those commitments and the scope of retained restrictions.

(ii)New GATS negotiating positions in education

To date,only the US,Australia and the New Zealand Governments have submitted proposals setting out their negotiating objectives for education services in the new GATS Round of talks.17

The main thrusts of the US proposal are as follows:

q It focuses on private education services,in the higher(tertiary)education and adult education and training sectors,envisaging that‘private education and training will continue to supplement,not displace,public education systems’.

q It recommends clarification of the classification issue,proposing that the classification of education services should clearly cover and distinguish two types of services:training and educational testing services.18 q It identifies a list of obstacles hindering trade in education services–e.g.

prohibition of education services offered by foreign entities,the lack of possibilities for authorisation to establish in a Member’s territory and to be recognised as a degree-conferring institution,economic needs tests and suggests that Members take these into account when making market-access commitments,as well as taking additional commitments relating to domestic regulation in the sector.

The Australian proposal recognises that governments play a significant role in the financing,delivery and regulation of education.However,it supports further liberalisation in educational services as a means of providing individuals in all countries with access to a wide range of educational options.It proposes, furthermore,that given that there are significant linkages between the regulatory

16The GATS preamble recognises,inter alia,‘the right of Members to regulate,and to introduce new regulations,on the supply of services within their territories in order to meet national policy objectives and,given asymmetries existing with respect to the degree of development of services regulations in different countries,the particular need of developing countries to exercise this right’. 17WTO,Communication from the United States,Higher(Tertiary)Education,Adult Education and Training,18December,2000(S/CSS/W/23);WTO,Communication from New Zealand, Negotiating Proposal for Education Services,26June,2001(S/CSS/W/93);WTO,Communication from Australia,Negotiating Proposal for Education Services,1October,2001(S/CSS/W/110). 18The former is relevant to higher,adult and other education services while the latter are related to all types of education;see op.cit.

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

864KURT LARSEN,JOHN P.MARTIN AND ROSEMARY MORRIS framework governing international trade in education services and other services sectors(for example,the telecommunication/audiovisual sector and movement of persons),there is a need for the education services negotiation to be viewed within the context of a comprehensive services round.

The New Zealand negotiating proposal recognises explicitly that the reduction of barriers to trade in education does not equate to an erosion of core public education systems and standards.It states that international trade in education services can provide a means of supplementing and supporting national education policy objectives.It goes on to recommend a more elaborated definition of the ‘Other education’category as follows:

All other education services not defined by level.These include short-term training courses, language training and practical/vocational courses in a range of subjects,for example computing,hospitality,resource management and primary production,together with education services offered by non-traditional providers,such as driver education programmes and corporate training services.

4.POLICY ISSUES ARISING FROM TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES

This section highlights four major policy issues arising from trade in educational services:

a.Absence of an International Framework of Quality Assurance and Accreditation in Higher Education

There is no agreed international quality framework for higher education. Without such a framework in place,foreign students cannot be confident that they are getting a quality higher education,and also,whether the qualifications that result will be valued on the labour market.Several attempts have been made to establish such a framework but so far only some regional agreements are in place in order to define international standards for providers of higher education and at the same time guarantee some consumer(learner)protection.

In countries that have relatively small and homogeneous university education systems,accreditation has not been a serious issue,quality assurance has been relatively straightforward,and qualifications relatively well understood.On the other hand,a country like the United States with its very diverse post-secondary education system,has much greater difficulties in this area,which is reflected in its complicated accreditation system with many different and not always co-ordinated accreditation bodies.

The same is the case in Europe,although recent policy initiatives try to address this issue.The Bologna declaration and the May2001meeting of European

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES:TRENDS AND ISSUES865

Education Ministers in Prague on a European Higher Education Area are steps towards the establishment of a common quality framework in an enlarged European Union.However,lying behind the very different national assurance and accreditation systems across OECD countries,are often different cultural values and understandings of what is important in higher education.

What are the prospects of creating an agreed international quality framework for higher education?It seems very unlikely that significant progress will be made on this goal soon.Indeed,it may be a chimera.The Bologna declaration is clearly a small step in this direction,but it covers only the enlarged Europe.In the United States,there are few signs of a‘harmonisation’of accreditation procedures and criteria across the country.There are some initiatives under way which try to develop international systems of accreditation and quality control.But such global initiatives are in their infancy.19

b.Impact of E-learning Providers on the Established Higher Education Market

Much has been said and written about the huge market potential of e-learning, but in reality it has proven to be much more difficult and costly to produce high-quality e-learning courses which can attract a significant number of students and make a profit for their providers.Nevertheless,the potential for a rapidly expanding cross-border e-learning market is there.

E-learning highlights an issue facing higher education institutions more generally the pressure to provide‘just-in-time delivery’to its clientele,rather than to set its own rules,timetables and content criteria.Many higher education institutions can no longer take their‘clients’for granted,and in many cases have to compete with private organisations and/or foreign universities/organisations. However,e-learning is still far from challenging campus education seriously.

E-learning is likely,nonetheless,to have a major influence on the future development of trade in educational services.First,it will most likely increase the number of students taking foreign courses while staying at least partly in their home country.Second,it will certainly accentuate the need for quality assurance, given that new multinational e-learning-based institutions with no physical presence in countries where they have students may be harder to subject to local systems of recognition and quality assurance.Third,it could give additional advantage to higher education institutions with strong brandnames and high reputations in the labour market if they decided to invest heavily in the e-learning 19The Global Alliance for Transnational Education,having so far accredited only four universities, is one such initiative.Another body,the Centre for Quality Assurance in International Education, aims to advise governments on quality assurance for foreign institutions,and in particular,promote globalisation of the professions.

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

866KURT LARSEN,JOHN P.MARTIN AND ROSEMARY MORRIS market.Finally,it might reduce the rate of growth in international student mobility.

c.The Regulation of Foreign Providers of Post-secondary Education

Many governments wish to use education to meet certain national objectives, and take the view that there is a risk that competition from a foreign supplier might compromise their ability to do so.As long as there is no agreed international quality framework for trade in post-secondary education and training services,there will be national concerns to regulate providers of post-secondary education from other countries.The growing cross-border e-learning activities will most likely accentuate national concerns to regulate these activities.However,any regulation of foreign providers of services raises issues of equal treatment with domestic providers of these services.It is important to note in this context that the GATS explicitly recognises the sovereign rights of governments to regulate in order to meet national policy objectives.In addition, the flexibility inherent in the way the Agreement is structured allows Members to not only choose the sectors and modes of supply for which they want to grant market access,but equally the conditions of market access,or in the case of unequal treatment post-establishment,conditions on national treatment.

d.Intellectual Property Rights of Learning Material

With growing trade in higher education services goes increased international competition between universities and other institutions of higher education across borders.In this situation,universities may be tempted to seek to protect their knowledge and learning materials and reputation through intellectual property rights.But there are counter-examples:the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)recently announced that it would in the next ten years make all its course material available free on the Internet.Free knowledge,however,is not the same thing as free learning.Putting course material on the Internet would not enable computer users everywhere to learn what students do who enrol at the university in question–a course of study consists of much more than just the supply of a set of materials.

5.CONCLUSIONS

Contrary to popular belief,there is significant trade in higher educational services:a rough estimate puts the value of this trade for OECD countries at about US$30billion in1999,equivalent to three per cent of their total services trade.This figure takes only into account students studying abroad in higher

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

TRADE IN EDUCATIONAL SERVICES:TRENDS AND ISSUES867 education and is undoubtedly an underestimate of the current level of trade in education services.The forces of comparative advantage have already identified some OECD countries that are leading net exporters of such services.Based on the limited available data,Australia appears to be the most competitive exporter in the market for educational services followed by New Zealand,the United Kingdom and the United States in that order.

Education is one of the sectors covered by the GATS for which WTO Members were the least inclined to schedule liberalisation commitments during the Uruguay Round.To date,only38Members have made commitments for at least one education sub-sector.WTO member countries have chosen to maintain considerably more limitations on trade in educational services in modes3and4 (‘commercial presence’and‘presence of natural persons’)than in modes1and2 (‘cross-border supply’and‘consumption abroad’).Furthermore,Member countries have,in general,put slightly more limitations on trade in primary and secondary education(considered as‘basic’schooling in many OECD countries)than on higher and adult education and training.

Technological innovation,symbolised by e-learning,is likely to have a major impact on this trade in the future.At the same time,there are in many countries very real concerns about the potential threats posed to cultural values and national traditions by growing trade liberalisation in education services.At the time of writing,only three countries–the United States,Australia and New Zealand–have submitted negotiating proposals on trade in respectively higher education and other education services in the on-going GATS negotiations.For this reason, any further multilateral liberalisation of trade in educational services is unlikely to involve public primary and secondary education;and further multilateral liberalisation of trade in higher education services,adult education and training,if it does occur,is probably still some way off.But this does not prevent exporting countries taking unilateral or bilateral initiatives to expand their market shares which involve liberalisation,e.g.by reducing barriers to the temporary stay of students,still the principal means of trade in the education sector.

Two inter-linked issues have to be addressed if further significant progress is to be made on liberalising trade in educational services.First,the importance of internationally-supplied educational services meeting certain quality standards is crucial.But the possibility of creating an international quality framework for higher education seems a long way off,even within the EU member states,let alone among the wider OECD or global community.This is despite the fact that both sides to the debate–those countries calling for more open trade in higher education services and those who wish no further liberalisation–agree on the need to develop new and more appropriate quality assurance frameworks world-wide.Second,many governments desire to use education to meet certain national objectives,and take the view that there is a real risk that competition from foreign suppliers might compromise their ability to do so.Ways have to be found to ?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

868KURT LARSEN,JOHN P.MARTIN AND ROSEMARY MORRIS alleviate this concern which might include,for example,placing certain conditions upon market access for foreign suppliers.

REFERENCES

AUCC(Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada)(2001),Canadian Higher Education and the GATS,AUCC background paper(February).

Bennell,P.and T.Pearce(1998),‘The Internationalisation of Higher Education:Exporting Education to Developing and Transitional Economics’,Working Paper(Institute of Development Studies).

Hartridge,D.(2000),‘Service Trade and Globalisation–Government Services and Public Policy Concerns(Speech given to the European Services Forum,Brussels,27November).

IDP Education Australia(2000),‘Transnational Education Providers,Partners and Policy–Challenges for Australian Institutions Offshore’(a Research Study presented at the14th Australian International Education Conference,Brisbane).

OECD(2000a),International Trade in Educational and Professional Services:Implications for Higher Education(Paris).

OECD(2000b),Education at a Glance(Paris).

OECD(2001a),Student Mobility Between and Towards OECD Countries–A Comparative Analysis(Paris).

OECD(2001b),‘Trade in Goods and Services:Statistical Trends and Measurement Challenges’, Statistics Brief,1(October).

US Department of Commerce(2000),U.S.International Services–Cross-Border Trade in1999 and Sales Through Affiliates in1998,Survey of Current Business(October2000,Washington DC).

WTO(2000),A Review of Statistics on Trade Flows in Services(30October,S/C/27/Add.1). WTO(2001),Market Access:Unfinished Business–Post-Uruguay Round Inventory and Issues, Special Study,6(Geneva,April).

?Blackwell Publishers Ltd2002

FOB贸易术语解释(中英文)

FOB贸易术语解释(中英文) FREE ON BOARD (... named port of shipment) “Free on Board" means that the seller delivers when the goods pass the ship''s rail at the named port of shipment. This means that the buyer has to bear all costs and risks of loss of or damage to the goods from that point. The FOB term requires the seller to clear the goods for export. This term can be used only for sea or inland waterway transport. If the parties do not intend to deliver the goods across the ship''s rail, the FCA term should he used. A THE SELLER''S OBLIGATIONS B THE BUYER''S OBLIGATIONS A1 Provision of goods in conformity with the contract The seller must provide the goods and the commercial invoice, or its equivalent electronic message, in conformity with the contract of sale and any other evidence of conformity winch may be required by the contract. B1 Payment of the price The buyer must pay the price as provided in the contract of sale. A2 Licences, authorisations and formalities The seller must obtain at his own risk and expense any export licence or other official authorisation and carry out, where applicable1 , all customs formalities necessary for the export of the goods. B2 Licences, authorisations and formalities

国际贸易术语中英文精修订

国际贸易术语中英文标准化管理部编码-[99968T-6889628-J68568-1689N]

外销员辅导物流货运费英文术语大全 海运费oceanfreight 集卡运费、短驳费Drayage 订舱费bookingcharge 报关费customsclearancefee 操作劳务费labourfeeorhandlingcharge 商检换单费exchangefeeforCIP 换单费D/Ofee 拆箱费De-vanningcharge 港杂费portsur-charge 电放费B/Lsurrenderfee 冲关费emergentdeclearationchange 海关查验费customsinspectionfee 待时费waitingcharge 仓储费storagefee 改单费amendmentcharge 拼箱服务费LCLservicecharge 动、植检疫费animal&plantquarantinefee 移动式其重机费mobilecranecharge 进出库费warehousein/outcharge 提箱费containerstuffingcharge 滞期费demurragecharge 滞箱费containerdetentioncharge 卡车运费cartagefee 商检费commodityinspectionfee 转运费transportationcharge 污箱费containerdirtynesschange 坏箱费用containerdamagecharge 清洁箱费containerclearancecharge 分拨费dispatchcharge 车上交货FOT(freeontrack) 电汇手续费T/Tfee 转境费/过境费I/Ebondedcharge

全套外贸术语 贸易术语 中英文对照

1. Trade-related Terms 贸易相关术语 A.贸易 Foreign Trade 对外贸易 Entrepot Trade F。)转口贸易 Home (Domestic)Trade 内贸 Coastal Trade 沿海贸易 Cross-border Trade 边境贸易 Barter Trade 易货贸易 Compensation Trade 补偿(互补)贸易 Bilateral trade (between China and the US)(中美)双边贸易Multilateral Trade ( Multilaterism ) 多边贸易 Trading House/Corporation/Firm/Company 贸易公司 Liner Trade 集装箱班轮运输 B.合同 Contract 合同 Active service contracts on file 在备有效服务合同

Sales Contract 销售合同 Sales Confirmation 销售确认书 Agreement 协议 Vessel sharing Agreement 共用舱位协议 Slot-sharing Agreement 共用箱位协议 Slot Exchange Agreement 箱位互换协议 Amendment 修正合同 Appendix 附录 Quota 配额 C.服务合同 Service Contract as provided in the Shipping Act of 1984, a contract between a shipper (or a shippers association)and an ocean carrier (or conference)in which the shipper makes a commitment to provide a certain minimum quantity of cargo or freight revenue over a fixed time period,and the ocean common carrier or

国际贸易术语(中英文对照)

分析证书certificate of analysis 一致性证书certificate of conformity 质量证书certificate of quality 测试报告test report 产品性能报告product performance report 产品规格型号报告product specification report 工艺数据报告process data report 首样测试报告first sample test report 价格/销售目录price /sales catalogue 参与方信息party information 农产品加工厂证书mill certificate 家产品加工厂证书post receipt 邮政收据post receipt 重量证书weight certificate 重量单weight list 证书ceitificate 价值与原产地综合证书combined certificate of value and origin 移动声明A.TR.1movement certificate A.TR.1 数量证书certificate of quantity 质量数据报文quality data message 查询query 查询回复response to query 订购单purchase order 制造说明manufacturing instructions 领料单stores requisition 产品售价单invoicing data sheet 包装说明packing instruction 内部运输单internal transport order 统计及其他管理用内部单证statistical and oter administrative internal docu-ments 直接支付估价申请direct payment valuation request 直接支付估价单direct payment valuation 临时支付估价单rpovisional payment valuation 支付估价单payment valuation 数量估价单quantity valuation request 数量估价申请quantity valuation request 合同数量单contract bill of quantities-BOQ 不祭价投标数量单unpriced tender BOQ 标价投标数量单priced tender BOQ 询价单enquiry 临时支付申请interim application for payment 支付协议agreement to pay 意向书letter of intent 订单order 总订单blanket order

贸易术语中英文对照

国际贸易—— 出口信贷 export credit 出口津贴 export subsidy 商品倾销 dumping 外汇倾销 exchange dumping 优惠关税 special preferences 保税仓库 bonded warehouse 贸易顺差 favorable balance of trade 贸易逆差 unfavorable balance of trade 进口配额制 import quotas 自由贸易区 free trade zone 对外贸易值 value of foreign trade 国际贸易值 value of international trade 普遍优惠制 generalized system of preferences-GSP 最惠国待遇 most-favored nation treatment-MFNT 价格条件—— 价格术语trade term (price term) 运费freight 单价 price 码头费wharfage

总值 total value 卸货费landing charges 金额 amount 关税customs duty 净价 net price 印花税stamp duty 含佣价price including commission 港口税portdues 回佣return commission 装运港portof shipment 折扣discount,allowance 卸货港port of discharge 批发价 wholesale price 目的港portof destination 零售价 retail price 进口许口证inportlicence 现货价格spot price 出口许口证exportlicence 期货价格forward price 现行价格(时价)current price/ prevailing price

13种贸易术语的比较归纳-贸易术语的归纳总结

13种贸易术语归纳对比

FOB、CIF、CFR异同比较: 共同点: 1、三种价格术语都适用于海运和内河运输,其承运人一般只限于船公司。 2、三种价格术语交货点均为装运港船舷风险点均以在装运港越过船舷即从卖方转移至买方。 3、费用点:卖方均要承担货物在装运港越过船舷为止的一切费用。 4、提单:卖方均需向买方提交已装船清洁提单。 5、装船通知:装运前后卖方均应及时向买方发出装船通知。 6、风险点:卖方在装运港将货物装船后的风险即转移到买方。

7、目的港的进口清关,费用等均由买方负责办理;装运港的装船,陆运,出口报关,办理许可证等均由卖方办理。 8、卖方都有在装运港安排订舱、配船的义务。 不同点: 1、价格术语后港口性质不一样,FOB后的港口指卖方所在国的港口,而CFR与CIF 后的港口指买方所在国的港口 2、费用构成不一样,报价不一样。FOB价格是考虑货物从原料购进、生产直到出口报关货物装到买方指定船舱同的一切费用和利润为止,而CFR是在FOB价格的基础上再加上海运费,CIF则是在FOB价格的基础上再加上海运费和保险费。 3、码头作业费的支付对象不同。按照谁支付海运费谁支付THC费用的原则,FOB价格条款中THC费用应由买方承担,CFR与CIF中THC应由卖方承担,现行国内THC标准为20‘柜370元,大柜40’为560元,THC费用应在贸易合同中明确注明由谁支付。 4、保险费支付、办理不同:FOB、CFR 保险由买方办理,卖方应于装船前通知买方;CIF 保险由卖方办理并支付保险费,卖方按合同条款,保险条款办理保险并将保险单交给买方。 5、装船通知告知买方时间不同:FOB价格和CFR在装船前告知买方,装船内容、装船细节以便买方有充足的时间办理货物海上保险而CIF是由卖方投保可在装船后几天内告知买方装船通知。 FCA、CPT、CIP异同比较: 共同点: 1、适用于任何运输方式,包括多式联运,也包括海运。在船舷无实际意义

全套外贸术语,贸易术语,中英文对照

1. Trade-related Terms贸易相关术语 A.贸易 Foreign Trade对外贸易 Entrepot Trade F。)转口贸易 Home(Domestic)Trade内贸 Coastal Trade沿海贸易 Cross-border Trade边境贸易 Barter Trade易货贸易 Compensation Trade补偿(互补)贸易 Bilateral trade(between China and the US)(中美)双边贸易Multilateral Trade ( Multilaterism )多边贸易 Trading House/Corporation/Firm/Company贸易公司 Liner Trade集装箱班轮运输 B.合同 Contract合同 Active service contracts on file在备有效服务合同 Sales Contract销售合同 Sales Confirmation销售确认书 Agreement协议 Vessel sharing Agreement共用舱位协议 Slot-sharing Agreement共用箱位协议 Slot Exchange Agreement箱位互换协议 Amendment修正合同 Appendix附录 Quota配额 C.服务合同 Service Contract as provided in the Shipping Act of 1984, a contract between a shipper(or a shippers association)and an ocean carrier (or conference)in which the shipper makes a commitment to provide a certain minimum quantity of cargo or freight revenue over a fixed time period,and the ocean common carrier or conference commits to a certain rate or rate schedules as wel as a defined service level(such as assured space,transit time, port rotation or similar service features)。The contract may also specify provisions in the event of non-performance on the part of either party服务合同 A service contract is a confidential contract between a VOCC and 1 or more shippers in which the shipper(s) make a cargo commitment, and the carrier makes a rate and service commitment. 服务合同是一家有船承运人与一个和多个托运人签订的保密合同,

体验商务英语综合教程中文双语对照版

体验商务英语综合教程3 第二版 双语对照版 Unit1 Made in Europe 欧洲制造 Almost every fashion label outside the top super-luxury brands is either already manufacturing in Asia or 5 thinking of it. Coach, the US leather goods maker, is a classic example. Over the past five years, it has lifted all its gross margins by manufacturing solely in low-cost markets. In March 2002 it closed its factory in Lares, Puerto Rico, its last company-owned plant, and outsources all its products. 除了顶级奢侈品牌外几乎所有的时尚品牌都已经在亚洲生产,或者正在考虑这么做。美国的皮革商品制造商蔻驰(Coach)就是一个经典的例子。在过去的五年中,它通过仅在低成本市场生产来提升毛利率。在2002年的3月,它关闭了在波多黎各拉雷斯的最后一间公司所属工厂,将所有产品全部外包。Burberry has many Asian licensing arrangements.In 2000 it decided to renew Sanyo's Japanese licence for ten years. This means that almost half of Burberry's sales at retail value will continue to be produced under license in Asia. At the same time however, Japanese consumers prefer the group's European-made products. 巴宝莉(Burberry)在亚洲持有许多许可授权安排。2000年它决定给日本三洋公司的特许授权延长十年。这意味着按零售价计算巴宝莉几乎一半的销售额将是亚洲授权生产的。但是同时,日本的消费者却偏好于该集团在欧洲生产的产

体验商务英语综合教程2 教案

外语系教案 第次课学时:授课时间:第周

Context: Unit 1 Title: Introductions The tone of a business relationship can be set by an initial introduction. It is important to make a good impression right from the first handshake. When meeting businesspeople for the first time, is it better to be formal or informal? If in doubt, advise students to adopt a more formal approach. Here are some points to remember when making business introductions in English-speaking Western countries: a.Introduce businesspeople in order of professional rank –the person of highest authority is introduced to others in the group in descending order, depending on their professional position. b.When possible, stand up when introductions are being made. c.If clients are present, they should be introduced first. d.The same and title of the person being introduced is followed by the name and title of the other person. PROCEDURES Lesson 1 Starting up Ss listen to four businesspeople and match the speakers to their business cards. Vocabulary 1: Job titles Ss list word as job titles or departments. Then Ss talk about their jobs or studies. Vocabulary 2: Nationalities Ss match countries and nationalities. Reading: Describing people This reading section can be completed in two parts. Ss can start preparatory work on the article about Phil Knight, the founder and CEO of Nike, and complete Exercise A. Lesson 2

2010国际贸易术语解释通则与2000比较

《2010国际贸易术语解释通则》与2000版的比较分析发表时间:2011-5-23 来源:《对外经贸实务》2011年第5期供稿作者:朱念 [导读] 贸易术语结构上的变化。贸易术语由13种减少为11种,贸易术语根据运输方式分为2组。 朱念钦州学院 2010年9月国际商会已经完成了《2010国际贸易术语解释通则》(以下简称《2010年通则》),已于2011年1月1日发布生效。与《2000年通则》相比,《2010年通则》更准确地标明了各方承担货 物运输风险和费用的责任条款。 一、《2010年通则》的实质性的主要修改 《2010年通则》在以下两大方面进行了六个方面实质性的修改: 1. 贸易术语结构上的变化。贸易术语由13种减少为11种,贸易术语根据运输方式分为2组。《2010年通则》删掉了4个D组术语:DAF、DES、DEQ和DDU,新增2个D组术语:DAT(Delivered At Terminal,终端交货)和DAP(Delivered At Place,指定地点交货)。 2. 术语义务项目上的变化。《2010年通则》中每种术语项下卖方在每一项目中的具体义务不再“对应”买方在同一项目中相应的义务,而是改为分别描述,并且各项目内容也有所调整。其中, 第一项和第十项改动较大,尤其是第十项要求卖方和买方分别要帮助对方提供包括与安全有关的信息和单据,并因此而向受助方索偿因此而发生的费用。 3. 新增DA T和DAP两个术语。《2010年通则》增加了DAT和DAP两个全新的术语,DA T下卖方需要承担把货物由目的地(港)运输工具上卸下的费用,DAP下卖方只需在指定目的地把货物处于买方控 制之下,而无须承担卸货费。这有助船舶管理公司理解货物买卖双方支付各种收费时的角色,弄清码头处理费的责任方,有助避免现时经常出现的码头处理费(THC)纠纷。 4. “船舷”的变化。《2010年通则》取消了“船舷”的概念,不再设定“船舷”的界限,只强调卖方承担货物装上船为止的一切风险,买方承担货物自装运港装上船开始起的一切风险。此次修 订最终删除了“船舷”的规定,强调在FOB,CFR和CIF下买卖双方的风险以货物在装运港口被装上船时为界,而不再规定一个明确的风险临界点。 5. 关于连环贸易的补充。大宗货物买卖中,货物常在一笔连环贸易下的运输期间被多次买卖,即“String Sales”(连环贸易)。着眼于贸易术语在这种贸易中的应用,《2010年通则》对此连 环贸易模式下卖方的交付义务做了细分,在相关术语中同时规定了“设法获取已装船货物”和将货物装船的义务,弥补了以前版本中在此问题上未能反映的不足。 6. 术语的内外贸适用的兼容性。考虑到对于一些大的区域贸易集团,如欧洲单一市场而言,国与国之间的边界手续已不那么重要了,《2010年通则》首次正式明确这些术语

常用国际贸易术语中英文对照

常用国际贸易术语中英文对照 A.A.R = against all risks 担保全险,一切险 A.B.No. = Accepted Bill Number 进口到单编号 A/C = Account 账号 AC. = Acceptance 承兑 acc = acceptance,accepted 承兑,承诺 a/c.A/C = account 帐,帐户 ackmt = acknowledgement 承认,收条[/color] a/d = after date 出票后限期付款(票据) ad.advt. = advertisement 广告 adv. = advice 通知(书) ad val. = Ad valorem(according to value) 从价税A.F.B. = Air Freight Bill 航空提单 Agt. = Agent 代理商 AI = first class 一级 AM = Amendment 修改书 A.M.T. = Air Mail Transfer 信汇 Amt. = Amount 额,金额 A.N. = arrival notice 到货通知 A.P. = account payable 应付账款

A/P = Authority to Purchase 委托购买 a.p. = additional premiun 附加保险费 A.R. = Account Receivable 应收款 Art. = Article 条款,项 A/S = account sales 销货清单 a/s = after sight 见票后限期付款 asstd. = Assorted 各色俱备的 att,.attn. = attention 注意 av.,a/v = average 平均,海损 a/v = a vista (at sight) 见票即付 经贸常用词缩写(D)、(E)DD/A =documents against acceptance, 承兑后交付单 = documents for acceptance,= documents attached, 备承兑单据 = deposit account 存款账号 d/a = days after acceptance 承兑后……日付款 D.A. = Debit advice 付款报单 D/D,D. = Demand draft,documentary draft 即期汇票,跟单汇票 d/d = day’s date (days after date) 出票后……日付款 d.f.,d.fet. = dead freight 空载运费(船) Disc. = Discount 贴现;折扣 DLT = Day Letter Telegram 书信电 D/N = debit note 借方通知

贸易术语中英文对照

贸易术语中英文对照

国际贸易—— 出口信贷export credit 出口津贴export subsidy 商品倾销dumping 外汇倾销exchange dumping 优惠关税special preferences 保税仓库bonded warehouse 贸易顺差favorable balance of trade 贸易逆差unfavorable balance of trade 进口配额制import quotas 自由贸易区free trade zone 对外贸易值value of foreign trade 国际贸易值value of international trade

普遍优惠制generalized system of preferences-GSP 最惠国待遇most-favored nation treatment-MFNT

卸货港port of discharge 批发价wholesale price 目的港portof destination 零售价retail price 进口许口证inportlicence 现货价格spot price 出口许口证exportlicence 期货价格forward price 现行价格(时价)current price/ prevailing price 国际市场价格world (International)Marketprice 离岸价(船上交货价)FOB-free on board

成本加运费价(离岸加运费价)C&F-cost and freight 到岸价(成本加运费、保险费价) CIF-cost,insurance and freight 交货条件—— 交货delivery 轮船steamship(缩写S.S) 装运、装船shipment 租船charter (the chartered shep) 交货时间time of delivery 定程租船voyage charter 装运期限time of shipment 定期租船time charter 托运人(一般指出口商)shipper,consignor

体验商务英语综合教程--Unit-4-答案

Unit 4 Advertising Part I Business Vocabulary Directions: There are 20 incomplete sentences in this part. For each sentence there are four choices marked A, B, C and D. Choose the ONE that best completes the sentence. Then mark the corresponding letter on the Answer Sheet with a single line through the center. This part totals 20 points, one point for each sentence. C1 Outdoor advertising is one of the fastest growing _______________ in the market. A markets B sections C segments D sectors D2 The world of outdoor advertising billboards, transport and ‘street furniture’is ______ about $18 billion a year, just 6% of all the worl d’s spending on advertising. A worthwhile B worthy C valued D worth C3 The soaring costs of TV are ______________ clients to consider alternatives. A making B driving C prompting D letting A4 BMW ran a ‘teasers’ campaign in Britain on bus shelters. A exclusively B largely C greatly D inclusively C5 Placing an ad on a bus shelter for two weeks ________________ at about £90. A works on B works away C works out D calculates D6 We are facing a ________________ with our market share. What are we going to do about it? A promotion B sale C order D crisis A7 Focus, a large advertising agency based in Paris, has a reputation for creating imaginative and ____________ campaigns. A effective B efficient C effect D efficacious C8 Focus now needs to ________________ potential clients that it still has plenty of creative ideas to offer. A ensure B assure C convince D persuade B9 Focus has been asked to _________________ ideas for advertising campaigns to managements of the companies concerned. A offer B present C supply D furnish

六种主要贸易术语的异同点比较

六种主要贸易术语的异同点比较 一、FOB、CFR、CIF的异同点 1.1.相同点 ⑴交货方式:FOB、CFR、CIF合同均属于象征性交货,即单据买卖。 ⑵运输方式:水上运输,包括海运及内河水运。 ⑶交货地点:装运港船上交货。 ⑷风险界点:装运港船舷为界,卖方承担货物越过装运港船舷之前的风险,买方承担货物越过装运港船舷之后的风险。 ⑸卖方的权利和义务:①提供货物及商业发票;②将货物交至船上并及时通知买方;③办理出口手续。 ⑹买方的权利和义务:①付款、接单、提货;②办理进口手续。 1.2.异同点 ⑴办理运输的责任的规定不同,CFR和CIF下由卖方办理运输,FOB合同下由买方办理。 ⑵办理保险的责任不同,CIF合同下由卖方办理保险,FOB和CFR下由买方办理保险。 ⑶术语后跟的地点不同,FOB后为指定装运港,CFR和CIF后为指定目的港。 ⑷价格构成不同,CFR=FOB+F;CIF=CFR+I。 二、FCA、CPT、CIP的异同点 2.1.相同点 ⑴交货方式:FCA、CPT、CIP合同均属于象征性交货,即单据买卖。 ⑵运输方式:任何方式(水上运输、航空运输、铁路运输、公路运输),包括多式联运。 ⑶交货地点:因运输方式不同时情况而定。 ⑷风险界点:货交第一承运人为界,卖方承担货物交到承运人之前的风险,买方承担货交承运人之后的风险。 ⑸卖方的权利和义务:①提供货物及商业发票;②将货物交至承运人;③办理出口手续。

⑹买方的权利和义务:①付款、接单、提货;②办理进口手续。 2.2.不同点 ⑴办理运输的责任的规定不同,CPT和CIP下由卖方办理运输,FCA合同下由买方办理。 ⑵办理保险的责任不同,CIP合同下由卖方办理保险,FCA和CPT下由买方办理保险。 ⑶术语后跟的地点不同,FCA后为指定地点,CPT和CIP后为指定目的地,因运输方式不同,视情况而定。 ⑷价格构成不同,CPT=FCA+F;CIP=CPT+I。 三、FOB和FCA、CFR和CPT、CIF和CIP的异同点 3.1.FOB和FCA的异同点 3.1.1.相同点 在交货方式、办理运输和保险的责任归谁、货物在运输途中的风险划分、货价构成、按术语签订的合同类型方面都相同。 3.1.2.不同点 ①适用的运输方式:FOB仅适合水上运输,因此交货地点只能在装运港;而FCA则适用于包括多式联运方式在内的任何运输方式,交货地点依运输方式的不同由双方加以约定; ②在风险及费用划分的具体界限方面也存在差距,FOB是以越过装运港船舷为界,FCA是以货交承运人为界。 3.2.CFR和CPT的异同点 3.2.1.相同点 ①都是由买方负责安排运输、将货物运往指定目的地、货物在运输过程中的风险都由买方承担、货价构成因素中都包括运费; ②它们都属于装运地交货的术语,签订的合同都属于装运合同,卖方只需保证按时交货,并不保证按时到货。 3.2.2.不同点 ①适用的运输方式:CFR仅适合水上运输,因此交货地点只能在装运港;而CPT则适用于包括多式联运方式在内的任何运输方式,交货地点依运输方式的不同由双方加以约定;

体验商务英语视听说答案

体验商务英语视听说答案【篇一:体验商务英语 4 综合教程】lass=txt> 一.课程基本信息课程编号:0142524 课程类别:选修 总学时:36 课程简介:商务英语课程作为翻译专业的一门专业先选课程,主要目标是培养学生掌握国际贸易的基础知识、基本技能,能独立从事一般的对外贸易业务工作。具备听说读写译的基本技能,语音语调正确、语法概念清楚,能用英语较熟练地从事外事接待、外贸业务洽谈的口、笔译工作。在培养学生英语语言能力的同时让学生了解和熟悉各种商务情景和商务活动,掌握相关的商务及商务文化知识,并使他们能够把所学的知识运用到各种商务活动中。二.教材简介 教材名称:体验商务英语综合教程4 教材编者:david cotton;david falvey; simon kent; 《体验商务英 语》改编组出版社:高等教育出版社 教材情况简介:本教材话题紧跟国际经济发展形势,循序渐进地训练学生用英语进行调研分析、归纳总结和使用正确语体作书面或口头表述的能力。既可以帮助在校生了解真实的商务环境和话题,学习地道的商务英语;也可以帮助从事各种经济活动的商务人员通过语言技能综合训,较快地提高语言能力。将国际商务活动引入课堂,体验真实的商务世界。角色扮演和案例学习将体验式学习引向深入,教学设计严谨,为体验式学习打好基础。教学资源丰富,为体验式教学提供有力支持。

三.课程教学内容 教学重点和难点 1. 重点:掌握各种商务活动情景对话中的语言要点及专业词汇 2. 难点:由于缺乏实战经验,学生难以理解不断涌现的商务方面的新知识和商务活动的实战环节。 教学内容、目标和学时分配 教学内容教学目标课时分配unit1communication 掌握 4 unit2international marketing 掌握4 unit3building relationships 掌握 4 unit 4 success 掌握 4 unit 5 job satisfaction 掌握 4 unit 6 risk 了解0 unit 7 e-commerce 掌握4 revision unit a unit 8team building 了解0 unit 9raising finance 了解0 unit 10 customer service 了解0 unit 11 crisis management 了解0 unit 12 management styles 掌握4 unit 13 takeovers and mergers 了解0 unit 14 the future of business 了解0 revision unit b 四.课程各教学环节的基本要求 课堂讲授:要求学生在课堂上就国际商务中的各种场景进行对话和听力练习,并通过看录像、vcd 及听录音和mp3 等多媒体手段提高学生的商务英语听说能力。作业:练习章节语言要点及专业词汇,布置角色扮演任务。mp3 或网络资源听力练习。 课程设计:本课程注重把语言技能的训练和专业知识有机结合起来。除了课堂讲解,有些练习属于开放式的,要求学生理论联系实际,认真独立地思考问题、深入探究问题、最终解决问题。在这一过程中学生的表达能力同时得以锻炼。4)测试: 测试方法:测试;闭卷;口试(其中平时成绩占30% ;测试成绩占70%) 五.教学参考书

六种主要贸易术语的异同点比较资料

六种主要贸易术语的 异同点比较 六种主要贸易术语的异同点比较 一、FOB、CFR、CIF 的异同点 1.1.相同点 ⑴交货方式:FOB、CFR、CIF合同均属于象征性交货,即单据买卖。 ⑵运输方式:水上运输,包括海运及内河水运。 ⑶交货地点:装运港船上交货。 ⑷风险界点:装运港船舷为界,卖方承担货物越过装运港船舷之前的风险,买方承担货物越过装运港船舷之后的风险。 ⑸卖方的权利和义务:①提供货物及商业发票;②将货物交至船上并及时通知买方;③办理出口手续。 ⑹买方的权利和义务:①付款、接单、提货:②办理进口手续。 1.2.异同点 ⑴办理运输的责任的规左不同,CFR和CIF下由卖方办理运输,FOB合同下由买方办理。 ⑵办理保险的责任不同,CIF合同下由卖方办理保险,FOB和CFR下由买方办理保险。

⑶术语后跟的地点不同,FOB后为指定装运港,CFR和CIF后为指龙目的港。 ⑷价格构成不同,CFR二FOB+F: CIF二CFR+I。 二、FCA、CPT、CIP 的异同点 2.1.相同点 ⑴交货方式:FCA、CPT、CIP合同均属于象征性交货,即单据买卖。 ⑵运输方式:任何方式(水上运输、航空运输、铁路运输、公路运输),包括多式联运。 ⑶交货地点:因运输方式不同时情况而泄。 ⑷风险界点:货交第一承运人为界,卖方承担货物交到承运人之前的风险,买方承担货交承运人之后的风险。 ⑸卖方的权利和义务:①提供货物及商业发票;②将货物交至承运人:③亦理出口手续。 ⑹买方的权利和义务:①付款、接单、提货:②办理进口手续。 2.2.不同点 ⑴办理运输的责任的规迫不同,CPT和CIP下由卖方办理运输,FCA合同下由买方办理。 ⑵办理保险的责任不同,CIP合同下由卖方办理保险,FCA和CPT下由买方办理保险。 ⑶术语后跟的地点不同,FCA后为指定地点,CPT和CIP后为指泄目的地,因运输方式不同,视情况而泄。 ⑷价格构成不同,CPT二FCA+F: CIP二CPT+I。 三、FOB和FCA、CFR和CPT、CIF和CIP的异同点 3.1.FOB和FCA的异同点 3.1.1.相同点 在交货方式、办理运输和保险的责任归谁、货物在运输途中的风险划分、货价构成、按术语签订的合同类型方面都相同。 3.1.2.不同点