英语专业论文翻译

A smart copper(II)-responsive binucleargadolinium(III) complex-based magnetic resonanceimaging contrast agent?

Yan-meng Xiao,ab Gui-yan Zhao,ab Xin-xiu Fang,ab Yong-xia Zhao,ab Guan-hua Wang,c Wei Yang*a and Jing-wei Xu*a

A novel Gd-DO3A-type bismacrocyclic complex, [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA], with a Cu2+-selective binding unitwas synthesized as a potential “smart” copper(II)-responsive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agent. The relaxivity of the complex was modulated by the presence or absence of Cu2+; in the absence of Cu2+, the complex exhibited a relatively low relaxivity value (6.40 mM 1 s 1), while the addition of Cu2+ triggered an approximately 76% enhancement in relaxivity (11.28 mM 1 s 1). Moreover, this Cu2+- responsive contrast agent was highly selective in its response to Cu2+ over other biologically-relevant metal ions. The influence of some common biological anions on the Cu2+-responsive contrast agent and the luminescence lifetime of the complex were also studied. The results of the luminescence lifetime measurements indicated that the enhancement in relaxivity was mainly ascribed to the increased number of inner-sphere water molecules binding to the paramagnetic Gd3+ core upon the addition of Cu2+. In addition, the visual change associated with the significantly enhanced relaxivity due to the addition of Cu2+ was observed from T1-weighted phantom images.

Introduction

Copper(II) ion is a vital metal nutrient for the metabolism of life and plays a critical role in various biological processes.1,2 Its homeostasis is critical for the metabolism and development of living organisms.3,4 On the other hand, the disruption of its homeostasis may lead to a variety of physical diseases and neurological problems such as Alzheimer's disease,5 Menkes and Wilson's disease,6 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,7,8 and prion disease.9,10 Therefore, the assessment and understanding of the distribution of biological copper in living systems by noninvasive imaging is crucial to provide more insight into copper homeostasis and better understand the relationship between copper regulation and its physiological function.

A wide variety of organic uorescent dyes have been exploited for the optical detection of ions in the last few decades.11–13However, optical imaging using organic uorescent dyes hasseveral limitations such as photobleaching, light scattering,limited penetration, low spatial resolution and the disturbance of auto uorescence.14 By comparison, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an increasingly accessible technique used as a noninvasive clinical diagnostic modality for medical diagnosis and biomedical research.15 It can provide high spatial resolution three-dimensional anatomical images with information about physiological signals and biochemical events.16 As a powerful diagnostic imaging tool in medicine, MRI can distinguish normal tissue from diseased tissue and lesions in a noninvasive manner,17–19 which avoids diagnostic thoracotomy or laparotomy surgery for medical diagnoses and greatly improves the diagnostic efficiency. Multiple MRI imaging parameters can provide a wealth of diagnostic information. In addition, the desired cross-section for acquiring multi-angle and multi-planar images of various parts of the entire body can be freely chosen by adjusting the MRI magnetic eld; this ability makes medical diagnostics and studies of the body's metabolism and function more and more effective and convenient. Contrast agents are often used in MRI examinations to improve the resolution and sensitivity; the image quality can be signicantly improved by applying contrast agents which enhance the MRI

signal intensity by increasing the relaxation rates of the surrounding water protons.20 Due to the high magnetic moment (seven unpaired electrons) and slow electronic relaxation of the

paramagnetic gadolinium(III) ion, gadolinium(III)-based MRI contrast agents are commonly employed to increase the relaxation rate of the surrounding water protons.16,21 However, most of these contrast agents are nonspecific and provide only anatomical information. On the basis of Solomon–Bloembergen–Morgan theory,22–24 several parameters can be manipulated to alter the relaxivity of gadolinium(III)-based MRI contrast agents. These parameters include the number of coordinated water molecules (q), the rotational correlation time (sR) and the residence lifetime of coordinated water molecules bound to the paramagnetic Gd3+ center (sM). Adjusting any of these three factors provides the opportunity to design “smart”MRI contrast agents for specifi c biochemical events.25–27 In recent years, there have been many studies on the development of responsive gadolinium(III)-based MRI contrast agents; most of them have focused on the development of targeted, high relaxivity and bioactivated contrast agents. These responsive gadolinium(III)-based MRI contrast agents can be modulated by particular in vivo stimuli including pH,28–35 metal ion concentration36–43 and enzyme activity.44–50 Notably, a number of copper-responsive MRI contrast agents have been reported to detect uctuations of copper ions in vivo.51–58 These activated contrast agents exploit the modulation of the number of coordinated water molecules to generate distinct enhancements in longitudinal relaxivity in response to copper ions (Cu+ or Cu2+).

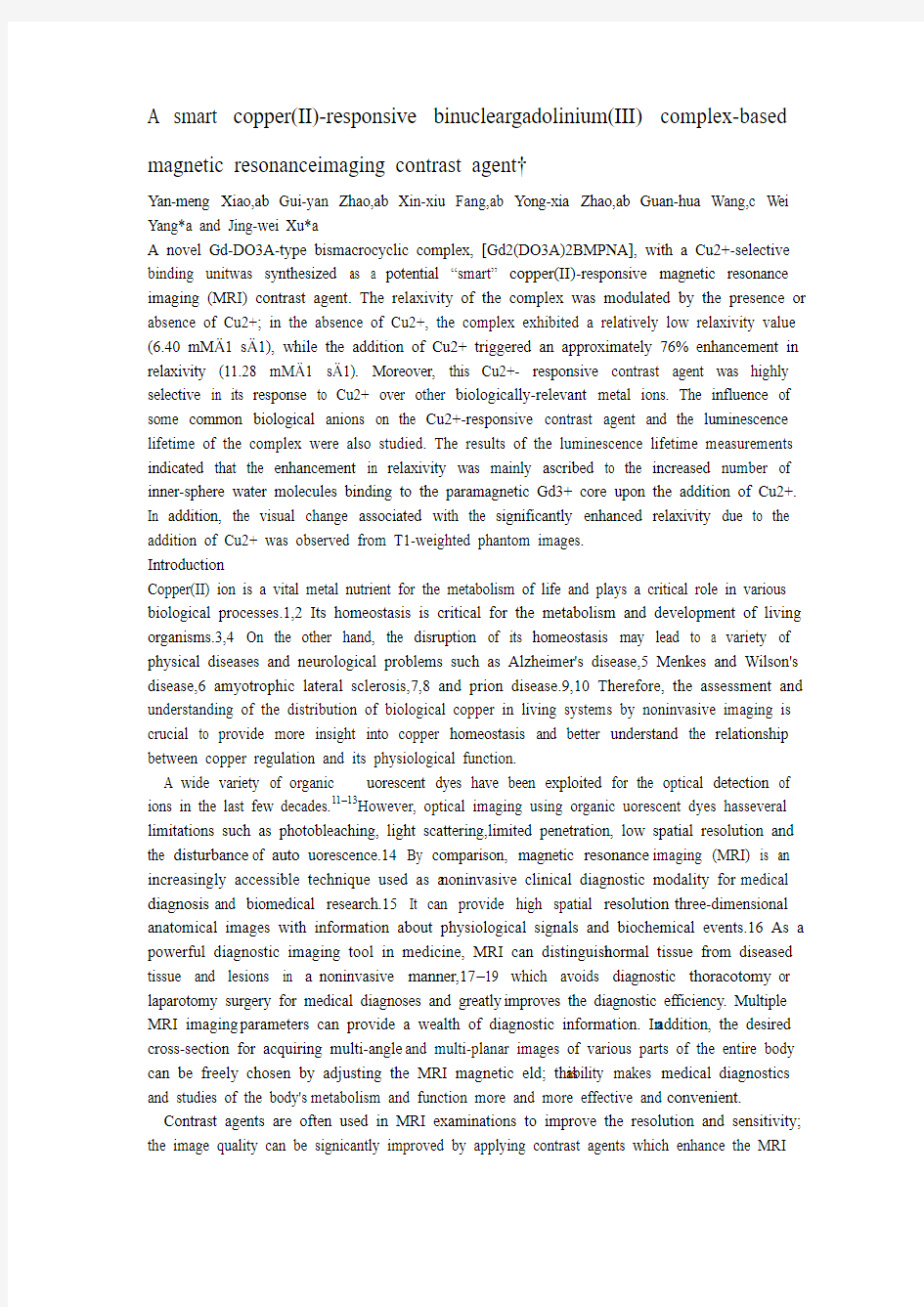

In this study, we designed and synthesized a binuclear gadolinium-based MRI contrast agent, [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA], that is specically responsive to Cu2+ over other biologicallyrelevant metal ions. The new copper-responsive MRI contrast agent comprises two Gd-DO3A cores connected by a 2,6-bis(3- methyl-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)isonicotinic acid scaffold59,60 (BMPNA), which functions as a receptor for copper-induced relaxivity switching. The synthetic strategy for [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] is depicted in Scheme 1. Subsequently, the T1 relaxivity of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] was studied at 25 C and 60 MHz in the absence or presence of Cu2+. Experiments to determine the selectivity of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] towards Cu2+ over other biologically-relevant ions were carried out as well. Luminescence lifetime was measured to determine the number of coordinated water molecules (q) of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] in the absence or presence of Cu2+. In addition, T1-weighted phantom images were collected to visualize the relaxivity enhancement caused by Cu2+, suggesting potential in vivo applications. Experimental section

Materials and instruments

All materials for synthesis were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purication. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were taken on an AMX600 Bruker FT-NMR spectrometer with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard. Luminescence measurements were performed on a Hitachi Fluorescence spectrophotometer-F-4600. The time-resolved luminescence emission spectra were recorded on a Perkin- Elmer LS-55 uorimeter with the following conditions: excitation wavelength, 295 nm; emission wavelength, 545 nm; dela time, 0.02 ms; gate time, 2.00 ms; cycle time, 20 ms; excitation slit, 5 nm; emission slit, 10 nm. The luminescence lifetime was measured on a Lecroy Wave Runner 6100 Digital Oscilloscope (1 GHz) using a tunable laser (pulse width ? 4 ns, gate ? 50 ns) as the excitation (Continuum Sunlite OPO). Mass spectra (MS) were obtained on an auto ex III TOF/TOF MALDI-MS and anIonSpec ESI-FTICR mass spectrometer. Elemental analyses were performed on a Vario EL Element Analyzer.

Synthesis

Synthesis of compound 3. Methyl 2,6-bis(3-(bromomethyl)-1H-pyrazol-1-yl) isonicotinate

(Compound1)59,60and 4,7,10- tris(2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethyl)-4,7,10-triaza-azoniacyclododecan-1-ium bromide (Compound 2)61 were prepared following thereported methods. Compound 2 (0.25 g, 0.296 mmol) was suspended in 2 ml anhydrous acetonitrile with 6 equivalents of NaHCO3 (0.1492 g) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 0.5 h. Compound 1 (0.0675 g, 0.148 mmol) was added, and the mixture was slowly heated to reflux (80 C) and stirred overnight. After the reaction was terminated, the mixture was cooled to room temperature, and the solution was ltered. The precipitate was washed several times with anhydrous acetonitrile, and the collected ltrate solution was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was puri ed using silicagel column chromatography eluted with CH2Cl2–n-hexane–CH3OH (10 : 3 : 1, v/v/v) to afford Compound 3 (0.1038 g, 53%) as a pale yellow solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO): 8.22 (s, 2H), 8.15 (s, 2H), 6.62 (s, 2H), 4.53 (s, 4H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.42 (m, 4H), 2.98 (m, 8H), 2.85 (s, 8H), 2.71 (m, 24H), 1.33 (s, 54H) (Fig. S1?).13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): d 173.21, 172.44, 163.99, 152.38, 150.11, 143.13, 128.07, 109.83, 108.36, 82.59, 57.84, 56.52, 56.06, 55.56, 52.98, 50.55, 48.91, 47.30, 27.96 (Fig. S2?). HRMS (ESI): m/z calc. for C67H111N13O14 [M + 2H]2+ 661.92650, [M + H + Na]2+ 672.91747, [M + 2Na]2+ 683.90844, found [M + 2H]2+ 661.92584, [M+ H + Na]2+ 672.91690, [M + 2Na]2+ 683.90682 (Fig. S3?).

Synthesis of compound 4. Compound 3 (0.1 g, 0.0756 mmol) was stirred with tri uoroacetic acid in methylene chloride solution (2 ml) at room temperature for 24 h. The solvent was then evaporated under reduced pressure, and the residue was washed three times in CH3OH and CH2Cl2 to eliminate excess acid. The obtained residue was dissolved with a minimum volume of CH3OH and precipitated with cold Et2O. The precipitate was ltered to afford a brown yellow solid (0.1022 g). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO): 9.06 (s, 2H), 8.17 (s, 2H), 6.84 (s, 2H), 4.33 (s, 4H), 3.98 (s, 3H), 3.56 (b, 20H), 3.09 (m, 24H) (Fig. S4?). 13C NMR (151 MHz, D2O): d 174.11, 169.13, 164.64, 150.75, 148.85, 142.10, 129.88, 109.75, 107.99, 55.69, 54.01, 53.10, 52.43, 51.15, 49.59, 48.22, 47.69 (Fig. S5?). MALDI-TOFMS spectrum (CH3OH): m/z calc. for C43H63N13O14 [M H] 984.46, found 984.7 (Fig. S6?). Anal calc. for C43H63N13O14- $3CF3COOH$2H2O: C, 43.14; H, 5.17; N, 13.35; found C, 42.34; H, 4.999; N, 13.29%. Preparation of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] and [Tb2(DO3A)2- BMPNA]. Compound 4 (0.05 mmol) was dissolved in 2 ml of highly-puri ed water. GdCl3 or TbCl3 (0.1 mmol) was added dropwise. The pH was maintained at 6.5–7.0 with NaOH during the whole process. The solution was then stirred at 75 C for 24 h. MALDI-MS (H2O): m/z calc. for C42H55N13O14Gd2 [M + H]+ 1281.46, found 1281.4 (Fig. S7?). MALDI-MS (H2O): m/z calc. for C42H55N13O14Tb2 [M + H]+ 1284.3, found 1284.4 (Fig. S8?).

T1measurements. The longitudinal relaxation times (T1) of aqueous solutions of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] were measured on an HT-MRSI60-25 spectrometer (Shanghai Shinning Globe Science and Education Equipment Co., Ltd) at 1.5 T. All of the tested samples were prepared in HEPES-buffered aqueous solutions at pH 7.4. All of the metal ions (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Fe3+, Fe2+) were used as chloride salts. Concentrations of Gd3+ were determined by ICP-OES. Relaxivities were determined from the slope of the plot of 1/T1 vs. [Gd]. The data were tted to the following eqn (1),20

(1/T1)obs?(1/T1)d + r1[M] (1)

where (1/T1)obs and (1/T1)d are the observed values in the presence and absence of the paramagnetic species, respectively, and [M] is the concentration of paramagnetic [Gd].

Luminescence measurements. Luminescence emission spectra were collected on a Hitachi uorescence spectrophotometer-F-4600. The luminescence lifetime was measured on a Lecroy Wave Runner 6100 Digital Oscilloscope (1 GHz) using a tunable laser (pulse width ? 4 ns, gate ? 50 ns) as the excitation (Continuum Sunlite OPO). Samples were excited at 290 nm, and the emission maximum (545 nm) was used to determine luminescence lifetimes. The Tb(III)-based emission spectra were measured using 0.1 mM solutions of Tb complex analog in 100 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.4 in H2O and D2O in the absence and presence of Cu2+. The number of coordinated water molecules (q) was calculated according to eqn (2):62,63

q= ? 5(sH2O 1 sD2O 1 0.06) (2)

T1-weighted MRI phantom images. Phantom images were collected on a 1.5 T HT-MRSI60-25 spectrometer (Shanghai Shinning Globe Science and Education Equipment Co., Ltd). Instrument parameter settings were as follows: 1.5 T magnet; matrix =256 256; slice thickness =1 mm; TE= 13 ms; TR= 100 ms; and number of acquisitions =1.

Results and discussion

Longitudinal relaxivity of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] in response to copper(II) ion

To investigate the in uence of Cu2+ on the relaxivity of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA], the longitudinal relaxivity r1 for the [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] contrast agent was determined using T1 measurements in the absence or presence of Cu2+ at 60 MHz and 25 C using a 0.2mMGd3+ solution of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] in 100 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) under simulated physiological conditions. The concentrations of Gd3+ were determined by ICP-OES. The relaxivity r1 was calculated from eqn (1). In the absence of Cu2+, the relaxivity of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] was 6.40 mM 1 s 1, which was higher than that of [Gd(DOTA)(H2O)] (4.2 mM 1 s 1, 20 MHz, 25 C) and Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2 (4.8 mM 1 s 1, 20 MHz, 40 C).64 Upon addition of up to 1 equiv. of Cu2+, the relaxivity of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] increased to 11.28 mM 1 s 1 (76% relaxivity enhancement). As shown in Fig. 1, the relaxivity gradually increased with the copper ion concentration, reaching a maximum value of approximately 1.2 equivalents of Cu2+. Due to the use of tri uoroacetic acid in the synthesis of Compound 4, tri uoroacetic acid residues produced CF3COO in the [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] solution, allowing CF3COO to partially coordinate with Cu2+ to form “Chinese lantern” type structure complexes.65 When the amount of added copper ions was further increased to above 1.2 equiv., the relaxivity was maintained at the same level. The observed difference in Cu2+-triggered relaxivity enhancement demonstrated the ability of this contrast agent to sense Cu2+ in vivo by means of MRI. Our designed contrast agent not only exhibited a higher relaxivity, but also displayed a Cu2+-responsive relaxivity enhancement.

Selectivity studies

The relaxivity response of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] exhibited excellent selectivity for Cu2+ over a variety of other competing, biologically-relevant metal ions at physiological levels. As depicted in Fig. 2 (white bars), the addition of alkali metal cations (10 mM Na+, 2 mM K+) and alkaline earth metal cations (2 mM Mg2+, 2 mM Ca2+) did not generate an increase in relaxivity compared to the copper ion turn-on response; even the introduction of d-block metal cations (0.2 mM Fe2+, 0.2 mM Fe3+, 0.2 mM or 2 mM Zn2+) did not trigger relaxivity enhancements. We noted that Zn2+ is also known to replace Gd3+ in transmetalation experiments; however, studies with analogous Gd3+-DO3A complexes demonstrated that this ligand is more kinetically inert to metal-ion exchange.66 To ensure the kinetic stability of the complex, we used MS to monitor [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] in the presence of 1 equiv. of Zn2+. No metal-ion exchange was observed at room temperature after 7 days (Fig. S13?). Relaxivity interference experiments for [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] in the presence of both Cu2+ (0.2 mM) and other biologically-relevant metal ions were also conducted; the results are shown as black bars in Fig. 2, indicating that these biologically-relevant metal ions (Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Zn2+) had no interference on the Cu2+-triggered relaxivity enhancement.

In addition, we also tested the Cu2+ response for [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] in the presence of physiologically-relevant concentrations of common biological anions to determine whether the Cu2+-triggered relaxivity enhancement was affected by biological anions at physiological levels. As previously mentioned, Cu2+ binding induced an enhancement in relaxivity from 6.40 mM 1 s 1 to 11.28 mM 1 s 1 (a 76% increase). As shown in Fig. 3, in the presence of citrate (0.13 mM), lactate (0.9 mM), H2PO4 (0.9 mM), or HCO3 (10 mM), the Cu2+-triggered relaxivity enhancement was approximately 61% (from 6.01 mM 1 s 1 to 9.66mM 1 s 1), 66% (from 6.13mM 1 s 1 to 10.16 mM 1 s 1), 20% (from 5.88 mM 1 s 1 to 7.02 mM 1 s 1), or 55% (from 6.15 mM 1 s 1 to 9.55 mM 1 s 1), respectively. Additionally, 100 mM NaCl had almost no effect (an approximately 75% increase), and a simulated extracellular anion solution (EAS, contain 30 mM NaHCO3, 100 mM NaCl, 0.9 mM KH2PO4, 2.3 mM sodium lactate, and 0.13 mM sodium citrate, pH =7),67 resulted in a Cu2+-triggered relaxivity enhancement of approximately 26% (from 6.02 mM 1 s 1 to 7.56 mM 1 s 1). Generally, the results revealed that lactate, citrate, and HCO3 had slight impacts on the Cu2+-triggered relaxivity enhancement, while H2PO4 and EAS influenced the enhancement to a greater degree. As shown in Scheme 2,

[Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] possessed two water molecules after the addition of 1 equiv. Of Cu2+.

According to the work of Dickins and coworkers, in lanthanide complexes with two water molecules, the waters can be partially displaced by phosphate, carbonate, acetate, carboxylate, lactate and citrate at different levels.68–70 The influence of these anions on the Cu2+-triggered relaxivity enhancement may be attributed to the partial replacement of coordinated water molecules by these anions. The relatively high concentration of phosphate could likely replace coordinated water molecules to reduce the increased number of water molecules surrounding the paramagnetic Gd3+ centre induced by Cu2+. As shown in Table 1, we measured the number of water molecules in the rst coordination sphere of Tb3+ in the presence of phosphate; the number of coordinated water molecules (q) decreased from 1.5 to 0.8.

Coordination features Luminescence lifetime experiments were performed to explore the mechanism of the Cu2+-triggered relaxivity enhancement. Luminescence lifetime measurements of lanthanide complexes have been widely used to quantify the number of inner-sphere water molecules.71 In particular, Tb3+ and Eu3+ have commonly been applied for lifetime measurements because their emission spectra are in the visible region when their 4f electrons are relaxed from higher energy levels to the lowest energy multiplets.72,73 Therefore, the Tb3+ analogue of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA], [Tb2(DO3A)2BMPNA], was prepared according to a similar method, and the luminescence lifetimes of the Tb3+ analogue in HEPES-buffered H2O and D2O in the absence and presence of Cu2+ were measured. As shown in Fig. S9,? the luminescence decay curve of [Tb2(DO3A)2BMPNA] was tted to obtain the luminescence lifetimes74 (Table 1), and the number of coordinated water molecules (q) was calculated by eqn (2). The analysis results (Table 1) for [Tb2(DO3A)2BMPNA] in HEPES-bufferedH2OandD2O in the absence and presence of Cu2+ indicated that q increased from 0.6 to 1.5 upon the addition of 1 equiv. of Cu2+; this result indicated that the Cu2+-triggered relaxivity enhancement for [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] was most likely due to the increased number of coordinated water molecules around the Gd3+ ion upon Cu2+ binding to the pyrazole centre (Scheme 2). A er the addition of Cu2+, Cu2+ removed the pyrazole centre N atom from the paramagnetic Gd3+ ion to generate an open coordination site available for a water molecule. Luminescence emission titrations of [Tb2(DO3A)2BMPNA] towards Cu2+ were also performed to investigate the binding properties of the contrast agent towards Cu2+. Upon addition of 1 equiv. Cu2+, the luminescence of [Tb2(DO3A)2BMPNA] at 545 nm decreased gradually and reached a minimum due to the quenching nature of the paramagnetic Cu2+ (Fig. S10?). The titration data indicated a 1 : 1 binding stoichiometry (Scheme 2) Copper-responsive T1-weighted phantom MRI in vitro To demonstrate the potential feasibility of this Cu2+-responsive [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] for copper-imaging applications, T1- weighted phantom images of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] were acquired in the absence and presence of copper ions. The phantom images depicted in Fig. 4 displayed distinct increases in image intensity in the presence of 1 equiv. Cu2+ compared with those without Cu2+ (Fig. 4D). Moreover, some of the other competing metal ions were also tested to further verify the selectivity of [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA] towards Cu2+. Discernible differences were not observed upon the addition of Mg2+ (Fig. 4C), Zn2+ (Fig. 4E), or Ca2+ (Fig. 4F). In addition, we also tested the clinical contrast agent Magnevist (Fig. 4G); the image intensity was a

bit darker than that of our contrast agent.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we designed and synthesized a novel bismacrocyclic DO3A-type Cu2+-responsive MRI contrast agent, [Gd2(DO3A)2BMPNA]. The new Cu2+-responsive MRI contrast agent comprised two Gd-DO3A cores connected by a 2,6-bis(3-methyl-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)isonicotinic acid scaffold (BMPNA) that functioned as a Cu2+ receptor switch to induce a distinct relaxivity enhancement in response to Cu2+; the relaxivity was increased up to 76%. Importantly, the complex exhibited high selectivity for Cu2+ over a range of other biologically-relevant metal ions at physiological levels. Luminescence lifetime experiment results showed that the number of inner-sphere water molecules (q) increased from 0.6 to 1.5 upon the addition of 1 equiv. Cu2+. When Cu2+ was coordinated in the central part of the complex, the donor N atom of the pyrazole centre was removed from the paramagnetic Gd3+ ion and replaced by a water molecule (Scheme 2). Consequently, the Cu2+-triggered relaxivity enhancement could be ascribed to the increase in the number of inner-sphere water molecules. The designed contrast agent had a longitudinal relaxivity of 6.40 mM 1 s 1, which was higher than that of [Gd(DOTA)(H2O)] (4.2 mM 1 s 1, 20 MHz, 25 C) and Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2 (4.8 mM 1 s 1, 20 MHz, 40 C). In addition, the visual change associated with the signi cantly enhanced relaxivity from the addition of Cu2+ was observed in T1-weighted phantom images.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the State Key Laboratory of Electroanalytical Chemistry for nancial support. Notes and references

1 S. Puig and D. J. Thiele, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., 2002, 6, 171.

2 S. C. Leary, D. R. Winge and P. A. Cobine, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj., 2009, 146, 1793.

3 D. D. Agranoff and S. Krishna, Mol. Microbiol., 1998, 28, 403.

4 H. Kozlowski, A. Janicka-Klos, J. Brasun, E. Gaggelli, D. Valensin and G. Valensin, Coord. Chem. Rev., 2009, 253, 2665.

5 K. J. Barnham, C. L. Masters and A. I. Bush, Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery, 2004, 3, 205.

6 D. J. Waggoner, T. B. Bartnikas and J. D. Gitlin, Neurobiol. Dis., 1999, 6, 221.

7 J. S. Valentine and P. J. Hart, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 2003, 100, 3617.

8 L. I. Bruijn, T. M. Miller and D. W. Cleveland, Annu. Rev. Neurosci., 2004, 27, 723.

9 G. L. Millhauser, Acc. Chem. Res., 2004, 37, 79.

10 D. R. Brown and H. Kozlowski, Dalton Trans., 2004, 1907.

11 A. W. Czarnik, Acc. Chem. Res., 1994, 27, 302.

12 L. Prodi, F. Bolletta, M. Montalti and N. Zaccheroni, Coord. Chem. Rev., 2000, 205, 59.

13 H. N. Kim, M. H. Lee, H. J. Kim, J. S. Kim and J. Yoon, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2008, 37, 1465.

14 M. Mahmoudi, V. Serpooshan and S. Laurent, Nanoscale, 2011, 3, 3007.

15 P. A. Rinck, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Blackwell Science, Berlin, 4th edn, 2001, p. 149.

16 A. E. Merbach and ′E. T′oth, The Chemistry of Contrast Agents in Medical Magnetic Resonance Imaging, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., New York, 2001.

17 S. Aime, E. Terreno, D. D. Castelli and A. Viale, Chem. Rev., 2010, 110, 3019.

18 S. Aime, M. Fasano and E. Terreno, Chem. Soc. Rev., 1998, 27, 19.

19 M. Woods, D. E. Woessner and A. D. Sherry, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2006, 35, 500.

20 R. B. Lauffer, Chem. Rev., 1987, 87, 901.

21 J. Kowalewski, D. Kruk and J. Parigi, Adv. Inorg. Chem., 2005, 57, 42.

22 I. Solomon, Phys. Rev., 1955, 99, 559.

23 N. Bloembergen, J. Chem. Phys., 1957, 27, 572.

24 N. Bloembergen and L. O. Morgan, J. Chem. Phys., 1961, 34, 842.

25 E. L. Que and C. J. Chang, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2010, 39, 51.

26 C. S. Bonnet and ′E. T′oth, Future Med. Chem., 2010, 2, 367.

27 L. Prodi, F. Bolletta, M. Montalti and N. Zaccheroni, Coord. Chem. Rev., 2000, 205, 59.

28 S. Aime, S. G. Crich, M. Botta, G. Giovenzana, G. Palmisano and M. Sisti, Chem. Commun., 1999, 1577.

29 J. Hall, R. Haner, S. Aime, M. Botta, S. Faulkner, D. Parker and A. S. de Sousa, New J. Chem., 1998, 22, 627.

30 M. P. Lowe and D. Parker, Chem. Commun., 2000, 707.

31 S. Aime, A. Barge, M. Botta, D. Parker and A. S. De Sousa, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 4767.

32 S. Aime, F. Fedeli, A. Sanino and E. Terreno, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006, 128, 11326.

33 M. P. Lowe, D. Parker, O. Reany, S. Aime, M. Botta, G. Castellano, E. Gianolio and R. Pagliarin, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2001, 123, 7601.

34 R. Hovland, C. Glogard, A. J. Aasen and J. Klaveness, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2, 2001, 929.

35 ′E. T′oth, R. D. Bolskar, A. Borel, G. Gonz′alez, L. Helm,

A. E. Merbach,

B. Sitharaman and L. J. Wilson, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2004, 127, 799.

36 W. H. Li, S. E. Fraser and T. J. Meade, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1999, 121, 1413.

37 K. Dhingra, M. E. Maier, M. Beyerlein, G. Angelovski and N. K. Logothetis, Chem. Commun., 2008, 3444.

38 H. Hifumi, A. Tanimoto, D. Citterio, H. Komatsu and K. Suzuki, Analyst, 2007, 132, 1153.

39 L. M. De Le′on-Rodr′?guez, A. J. M. Lubag, J. A. L′opez,G. Andreu-de-Riquer, J. C. Alvarado-Monz′on and A. D. Sherry, MedChemComm, 2012, 3, 480.

40 R. Trokowski, J. Ren, F. K. Kalman and A. D. Sherry, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2005, 44, 6920.

41 W. S. Li, J. Luo, F. Jiang and Z. N. Chen, Dalton Trans., 2012, 41, 9405.

42 K. Hanaoka, K. Kikuchi, Y. Urano and T. Nagano, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2, 2001, 1840.

43 R. Ruloff, G. v. Koten and A. E. Merbach, Chem. Commun., 2004, 842.

44 M. Giardiello, M. P. Lowe and M. Botta, Chem. Commun., 2007, 4044.

45 M. Andrews, A. J. Amoroso, L. P. Harding and S. J. A. Pope, Dalton Trans., 2010, 3407.

46 W. Xu and Y. Lu, Chem. Commun., 2011, 47, 4998.

47 R. A. Moats, S. E. Fraser and T. J. Meade, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 1997, 36, 726.

48 A. Y. Louie, M. M. Huber, E. T. Ahrens, U. Rothbacher,

R. Moats, R. E. Jacobs, S. E. Fraser and T. J. Meade, Nat. Biotechnol., 2000, 18, 321.

49 B. Yoo and M. D. Pagel, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006, 128, 14032.

50 Q. Wei, G. K. Seward, P. A. Hill, B. Patton, I. E. Dimitrov,

N. N. Kuzma and I. J. Dmochowski, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006, 128, 13274.

51 E. L. Que and C. J. Chang, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006, 128, 15942.

52 E. L. Que, E. Gianolio, S. L. Baker, A. P. Wong, S. Aime and C. J. Chang, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 8527.

53 E. L. Que, E. Gianolio, S. L. Baker, S. Aime and C. J. Chang, Dalton Trans., 2010, 39, 469.

54 W. S. Li, J. Luo and Z. N. Chen, Dalton Trans., 2011, 484.

55 E. L. Que, E. J. New and C. J. Chang, Chem. Sci., 2012, 3, 1829.

56 M. Andrews, A. J. Amoroso, L. P. Harding and S. J. A. Pope, Dalton Trans., 2010, 3407.

57 D. Kasala, T. S. Lin, C. Y. Chen, G. C. Liu, C. L. Kao, T. L. Cheng and Y. M. Wang, Dalton Trans., 2011, 5018.

58 D. Patel, A. Kell, B. Simard, B. Xiang, H. Y. Lin and G. Tian, Biomaterials, 2011, 32, 1167.

59 E. Brunet, O. Juanes, R. Sedano and J. C. Rodr′?guez-Ubis, Photochem. Photobiol. Sci., 2002, 1, 613.

60 Z. Q. Ye, G. L. Wang, J. X. Chen, X. Y. Fu, W. Z. Zhang and J. L. Yuan, Biosens. Bioelectron., 2010, 26, 1043.

61 S. Mizukami, K. Tonai, M. Kaneko and K. Kikuchi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2008, 130, 14376.

62 W. D. Horrocks and D. R. Sudnick, Acc. Chem. Res., 1981, 14, 384.

63 S. Quici, M. Cavazzini, G. Marzanni, G. Accorsi, N. Armaroli, B. Vcntura and F. Barigelletti, Inorg. Chem., 2005, 44, 529.

64 P. Caravan, J. J. Ellison, T. J. McMurry and R. B. Laufer, Chem. Rev., 1999, 99, 2293.

65 O. G. Polyakov, B. G. Nolan, B. P. Fauber, S. M. Miller, O. P. Anderson and S. H. Strauss, Inorg. Chem., 2000, 39, 1735.

66 M. F. Tweedle, J. J. Hagan, K. Kumar, S. Mantha and C. A. Chang, Magn. Reson. Imaging, 1991, 9, 409.

67 D. Parker, Coord. Chem. Rev., 2000, 205, 109.

68 R. S. Dickins, T. Gunnlaugsson, D. Parker and R. D. Peacock, Chem. Commun., 1998, 1643.

69 J. I. Bruce, R. S. Dickins, L. J. Govenlock, T. Gunnlaugsson, S. Lopinski, M. P. Lowe, D. Parker, R. D. Peacock, J. J. B. Perry, S. Aime and M. Botta, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2000, 122, 9674.

70 R. S. Dickins, S. Aime, A. S. Batsanov, A. Beeby, M. Botta, J. I. Bruce, J. A. K. Howard, C. S. Love, D. Parker, R. D. Peacock and H. Puschmann, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 12697–12705.

71 W. D. Horrocks and D. R. Sudnick, Acc. Chem. Res., 1981, 14, 384.

72 C. C. Bryden and C. N. Reilley, Anal. Chem., 1982, 54, 610.

73 K. Binnemans, Chem. Rev., 2009, 109, 4283.

74 S. Quici, M. Cavazzini, G. Marzanni, G. Accorsi, N. Armaroli, B. Vcntura and F. Barigelletti, Inorg. Chem., 2005, 44, 529. This journal is ? The Royal Society of Chemistry 2014 RSC Adv., 2014, 4, 34421–34427 | 34427

英文论文及中文翻译

International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials Volume 17, Number 4, August 2010, Page 500 DOI: 10.1007/s12613-010-0348-y Corresponding author: Zhuan Li E-mail: li_zhuan@https://www.360docs.net/doc/f613879584.html, ? University of Science and Technology Beijing and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2010 Preparation and properties of C/C-SiC brake composites fabricated by warm compacted-in situ reaction Zhuan Li, Peng Xiao, and Xiang Xiong State Key Laboratory of Powder Metallurgy, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China (Received: 12 August 2009; revised: 28 August 2009; accepted: 2 September 2009) Abstract: Carbon fibre reinforced carbon and silicon carbide dual matrix composites (C/C-SiC) were fabricated by the warm compacted-in situ reaction. The microstructure, mechanical properties, tribological properties, and wear mechanism of C/C-SiC composites at different brake speeds were investigated. The results indicate that the composites are composed of 58wt% C, 37wt% SiC, and 5wt% Si. The density and open porosity are 2.0 g·cm–3 and 10%, respectively. The C/C-SiC brake composites exhibit good mechanical properties. The flexural strength can reach up to 160 MPa, and the impact strength can reach 2.5 kJ·m–2. The C/C-SiC brake composites show excellent tribological performances. The friction coefficient is between 0.57 and 0.67 at the brake speeds from 8 to 24 m·s?1. The brake is stable, and the wear rate is less than 2.02×10?6 cm3·J?1. These results show that the C/C-SiC brake composites are the promising candidates for advanced brake and clutch systems. Keywords: C/C-SiC; ceramic matrix composites; tribological properties; microstructure [This work was financially supported by the National High-Tech Research and Development Program of China (No.2006AA03Z560) and the Graduate Degree Thesis Innovation Foundation of Central South University (No.2008yb019).] 温压-原位反应法制备C / C-SiC刹车复合材料的工艺和性能 李专,肖鹏,熊翔 粉末冶金国家重点实验室,中南大学,湖南长沙410083,中国(收稿日期:2009年8月12日修订:2009年8月28日;接受日期:2009年9月2日) 摘要:采用温压?原位反应法制备炭纤维增强炭和碳化硅双基体(C/C-SiC)复合材

英语翻译论文开题报告精编版

英语翻译论文开题报告 精编版 MQS system office room 【MQS16H-TTMS2A-MQSS8Q8-MQSH16898】

英语翻译论文开题报告 时间:2015-03- 12Bell.?Translation?and?Translating:?Theory?and?Practice.?Beijing:?Forei gn?Language?Teaching?and?Research?Press,?2006. 崔长青,?张碧竹.?翻译的要素[M].?苏州:?苏州大学出版社,?2007. 李琏.?英式显性词性转换与英语写作[J].?新疆教育学学 报,?2003,?19(1):?85-89. 李连生.?英汉互译中的词性转换[J].?武汉交通管理干部学院学 报,?1996,?(1):102-107. 项伙珍.?谈翻译中的转性译法[J].?长江职工大学学报,?2000,?17(3):?46-48. 叶海燕.?翻译中的词性转换及换形[J].?安徽工业大学学报(社会科学 版),?2005,?22(3):60-61. (责任编辑:1025) 三、对英文翻译中词类转换的引入 从语言的角度来分析,对一门语言中的词性以及在语句中的成分进行分析,?从转喻理论的相关知识出发,来探讨英汉语言翻译中词类转换的概念和知识,并就其异同和特性进行对比,不仅是当前国内外学者研究的重点问题,也是大学英语教学中始终关注的热点。?为?此?,从英文翻译的实践中,?通过例证或典型问题的互译,从语言结构及表达习惯上进行探讨英文翻译中的转换方法,以增强语言翻译的可读性和准确性,并从中探讨出词类转换的规律,帮助更多的学生从中获得有益的指

毕业论文英文参考文献与译文

Inventory management Inventory Control On the so-called "inventory control", many people will interpret it as a "storage management", which is actually a big distortion. The traditional narrow view, mainly for warehouse inventory control of materials for inventory, data processing, storage, distribution, etc., through the implementation of anti-corrosion, temperature and humidity control means, to make the custody of the physical inventory to maintain optimum purposes. This is just a form of inventory control, or can be defined as the physical inventory control. How, then, from a broad perspective to understand inventory control? Inventory control should be related to the company's financial and operational objectives, in particular operating cash flow by optimizing the entire demand and supply chain management processes (DSCM), a reasonable set of ERP control strategy, and supported by appropriate information processing tools, tools to achieved in ensuring the timely delivery of the premise, as far as possible to reduce inventory levels, reducing inventory and obsolescence, the risk of devaluation. In this sense, the physical inventory control to achieve financial goals is just a means to control the entire inventory or just a necessary part; from the perspective of organizational functions, physical inventory control, warehouse management is mainly the responsibility of The broad inventory control is the demand and supply chain management, and the whole company's responsibility. Why until now many people's understanding of inventory control, limited physical inventory control? The following two reasons can not be ignored: First, our enterprises do not attach importance to inventory control. Especially those who benefit relatively good business, as long as there is money on the few people to consider the problem of inventory turnover. Inventory control is simply interpreted as warehouse management, unless the time to spend money, it may have been to see the inventory problem, and see the results are often very simple procurement to buy more, or did not do warehouse departments . Second, ERP misleading. Invoicing software is simple audacity to call it ERP, companies on their so-called ERP can reduce the number of inventory, inventory control, seems to rely on their small software can get. Even as SAP, BAAN ERP world, the field of

电气自动化专业毕业论文英文翻译

电厂蒸汽动力的基础和使用 1.1 为何需要了解蒸汽 对于目前为止最大的发电工业部门来说, 蒸汽动力是最为基础性的。 若没有蒸汽动力, 社会的样子将会变得和现在大为不同。我们将不得已的去依靠水力发电厂、风车、电池、太阳能蓄电池和燃料电池,这些方法只能为我们平日用电提供很小的一部分。 蒸汽是很重要的,产生和使用蒸汽的安全与效率取决于怎样控制和应用仪表,在术语中通常被简写成C&I(控制和仪表 。此书旨在在发电厂的工程规程和电子学、仪器仪表以 及控制工程之间架设一座桥梁。 作为开篇,我将在本章大体描述由水到蒸汽的形态变化,然后将叙述蒸汽产生和使用的基本原则的概述。这看似简单的课题实际上却极为复杂。这里, 我们有必要做一个概述:这本书不是内容详尽的论文,有的时候甚至会掩盖一些细节, 而这些细节将会使热力学家 和燃烧物理学家都为之一震。但我们应该了解,这本书的目的是为了使控制仪表工程师充 分理解这一课题,从而可以安全的处理实用控制系统设计、运作、维护等方面的问题。1.2沸腾:水到蒸汽的状态变化 当水被加热时,其温度变化能通过某种途径被察觉(例如用温度计 。通过这种方式 得到的热量因为在某时水开始沸腾时其效果可被察觉,因而被称为感热。 然而,我们还需要更深的了解。“沸腾”究竟是什么含义?在深入了解之前,我们必须考虑到物质的三种状态:固态,液态,气态。 (当气体中的原子被电离时所产生的等离子气体经常被认为是物质的第四种状态, 但在实际应用中, 只需考虑以上三种状态固态,

物质由分子通过分子间的吸引力紧紧地靠在一起。当物质吸收热量,分子的能量升级并且 使得分子之间的间隙增大。当越来越多的能量被吸收,这种效果就会加剧,粒子之间相互脱离。这种由固态到液态的状态变化通常被称之为熔化。 当液体吸收了更多的热量时,一些分子获得了足够多的能量而从表面脱离,这个过程 被称为蒸发(凭此洒在地面的水会逐渐的消失在蒸发的过程中,一些分子是在相当低的 温度下脱离的,然而随着温度的上升,分子更加迅速的脱离,并且在某一温度上液体内部 变得非常剧烈,大量的气泡向液体表面升起。在这时我们称液体开始沸腾。这个过程是变为蒸汽的过程,也就是液体处于汽化状态。 让我们试想大量的水装在一个敞开的容器内。液体表面的空气对液体施加了一定的压 力,随着液体温度的上升,便会有足够的能量使得表面的分子挣脱出去,水这时开始改变 自身的状态,变成蒸汽。在此条件下获得更多的热量将不会引起温度上的明显变化。所增 加的能量只是被用来改变液体的状态。它的效用不能用温度计测量出来,但是它仍然发生 着。正因为如此,它被称为是潜在的,而不是可认知的热量。使这一现象发生的温度被称为是沸点。在常温常压下,水的沸点为100摄氏度。 如果液体表面的压力上升, 需要更多的能量才可以使得水变为蒸汽的状态。 换句话说, 必须使得温度更高才可以使它沸腾。总而言之,如果大气压力比正常值升高百分之十,水必须被加热到一百零二度才可以使之沸腾。

1外文文献翻译原文及译文汇总

华北电力大学科技学院 毕业设计(论文)附件 外文文献翻译 学号:121912020115姓名:彭钰钊 所在系别:动力工程系专业班级:测控技术与仪器12K1指导教师:李冰 原文标题:Infrared Remote Control System Abstract 2016 年 4 月 19 日

红外遥控系统 摘要 红外数据通信技术是目前在世界范围内被广泛使用的一种无线连接技术,被众多的硬件和软件平台所支持。红外收发器产品具有成本低,小型化,传输速率快,点对点安全传输,不受电磁干扰等特点,可以实现信息在不同产品之间快速、方便、安全地交换与传送,在短距离无线传输方面拥有十分明显的优势。红外遥控收发系统的设计在具有很高的实用价值,目前红外收发器产品在可携式产品中的应用潜力很大。全世界约有1亿5千万台设备采用红外技术,在电子产品和工业设备、医疗设备等领域广泛使用。绝大多数笔记本电脑和手机都配置红外收发器接口。随着红外数据传输技术更加成熟、成本下降,红外收发器在短距离通讯领域必将得到更广泛的应用。 本系统的设计目的是用红外线作为传输媒质来传输用户的操作信息并由接收电路解调出原始信号,主要用到编码芯片和解码芯片对信号进行调制与解调,其中编码芯片用的是台湾生产的PT2262,解码芯片是PT2272。主要工作原理是:利用编码键盘可以为PT2262提供的输入信息,PT2262对输入的信息进行编码并加载到38KHZ的载波上并调制红外发射二极管并辐射到空间,然后再由接收系统接收到发射的信号并解调出原始信息,由PT2272对原信号进行解码以驱动相应的电路完成用户的操作要求。 关键字:红外线;编码;解码;LM386;红外收发器。 1 绪论

英语文章及翻译

精心整理 Whatsportsandotheractivitiesdoyouparticipatein?Whatkindsoffoodsdoyoueat?Whatkindofpe opledoyouspendtimewith?Youranswerstotheseandsimilarquestionsreflectyourtotalhealth.He alth is acombinationofphysical,mental/emotional,andsocialwell-being.Thesepartsofyourhea lthworktogethertobuildgoodoverallhealth. 你参加过什么体育活动和其他活动吗?你吃什么食物?你和什么样的人在一起?你对这些问题或者类似的问题的回答反映出了你整体的健康状况。健康是身体、心里和社会安宁感的集合。这些健康的部分结合起来搭建了一个完整的健康体系。 通常,觉更好, t 身体须要远离有害的物质像烟草、酒精和其他毒品。他们用体育运动的时间去平衡他们看电视或玩电脑游戏的时间。体育运动包括做特殊的运动,远足,健身操,游泳,跳舞和做一份工作。通过远离有害物质和坚持体育运动,你可以保持身体健康。另外一种说法就是,要想身体健康就要多运动。 Doyoufeelgoodaboutwhoyouare?Doyouknowhowtohandlestressfulsituations?Doyouhaveapositiv eattitudeaboutlife?Youranswerstothesequestionswilltellyousomethingaboutyourmental/emo tionalhealth.Mental/emotionalhealthismeasuredbythewayyouthinkandexpressyourfeelings.Y oucandevelopgoodmental/emotionalhealthbylearningtothinkpositivelyandtoexpressyourfeel ingsinhealthyways.Positivethinkingisagoodstrategytousewhenyouarefeelingsadordown.Tryf ocusingyourattentiononallofthegoodthingsinyourlife,suchasyourfriends,family,andactivi tiesyouenjoy.Thenthecauseofyoursadnessmightnotseemsobad.Likewise,recognizingandbuildi

英语翻译翻译方向论文题目

English Novel Title Translation: A Skopostheorie Perspective 英语小说标题的翻译:一个Skopostheorie透视图 The Translation of Fuzziness in the Dialogue of Fortress Besieged from the Perspective of Relevance Theory翻译的模糊性的对话《围城》从关联理论的角度 On Domestication Strategy in Advertisement Slogan Translation 在归化策略在广告口号的翻译 Reproduction of “Three Beauties” in the Translation of the Poems in The Journey to the West 繁殖的“三美”翻译的诗歌在西游记 A Comparative Study of Interjection Translation in Teahouse from the Perspective of Functional Equivalence一个比较研究,在茶馆的感叹词翻译功能对等的角度 Public Signs Translation from the Perspective of Functionalist Theory --Taking Shaoyang City as an Example公共标志的翻译的角度,从实用主义的理论——以邵阳城市作为一个例子 The Application of Skopostheory in the Business Advertisement Translation Skopostheory的应用在商业广告翻译 Relevance Theory Applied in the Translation of Neologism 关联理论应用于翻译的新词 Domestication and Foreignization in the Translation of Tourist Texts 归化和异化在翻译旅游文本 A Comparative Study of the Two English Versions of Lun Y u by James Legge and Ku Hongming from Translator's Subjectivity一个比较研究的两个英文版本的Lun Yu詹姆斯Legge和Ku Hongming从译者的主体性 On the Translation and Functions of Metaphor in Advertisements 在翻译和函数中隐喻的广告 C-E Translation of Film Titles from the Perspective of Adaptation Theory 汉英翻译的电影片名的角度,从适应理论 Pun Advertisements Translation From the Perspective of Adaptation Theory 广告双关语翻译的角度,从适应理论 Analysis of the Translation Strategies of the Culture-loading Words in the English Version of Journey to the West分析的翻译策略在英语文化加载字版的西游记 On Business Letter Translation under the Guidance of Conversational Implicature Theory 在商务信函翻译的指导下,会话含义理论 On the Translation of Puns in English Advertising 在翻译双关语在英语广告 Advertising Translation in the View of Skopos Theory 广告翻译目的论的观点 A study on Trademark Translation from the Perspective of Reception Aesthetics 商标翻译的研究从接受美学的角度

英语专业毕业论文翻译类论文

英语专业毕业论文翻译 类论文 Document number:NOCG-YUNOO-BUYTT-UU986-1986UT

毕业论文(设计)Title:The Application of the Iconicity to the Translation of Chinese Poetry 题目:象似性在中国诗歌翻译中的应用 学生姓名孔令霞 学号 BC09150201 指导教师祁晓菲助教 年级 2009级英语本科(翻译方向)二班 专业英语 系别外国语言文学系

黑龙江外国语学院本科生毕业论文(设计)任务书 摘要

索绪尔提出的语言符号任意性,近些年不断受到质疑,来自语言象似性的研究是最大的挑战。语言象似性理论是针对语言任意性理论提出来的,并在不断发展。象似性是当今认知语言学研究中的一个重要课题,是指语言符号的能指与所指之间的自然联系。本文以中国诗歌英译为例,探讨象似性在中国诗歌翻译中的应用,从以下几个部分阐述:(1)象似性的发展;(2)象似性的定义及分类;(3)中国诗歌翻译的标准;(4)象似性在中国诗歌翻译中的应用,主要从以下几个方面论述:声音象似、顺序象似、数量象似、对称象似方面。通过以上几个方面的探究,探讨了中国诗歌翻译中象似性原则的重大作用,在诗歌翻译过程中有助于得到“形神皆似”和“意美、音美、形美”的理想翻译效果。 关键词:象似性;诗歌;翻译

Abstract The arbitrariness theory of language signs proposed by Saussure is severely challenged by the study of language iconicity in recent years. The theory of iconicity is put forward in contrast to that of arbitrariness and has been developing gradually. Iconicity, which is an important subject in the research of cognitive linguistics, refers to a natural resemblance or analogy between the form of a sign and the object or concept. This thesis mainly discusses the application of the iconicity to the translation of Chinese poetry. The paper is better described from the following parts: (1) The development of the iconicity; (2) The definition and classification of the iconicity; (3) The standards of the translation to Chinese poetry; (4) The application of the iconicity to the translation of Chinese poetry, mainly discussed from the following aspects: sound iconicity, order iconicity, quantity iconicity, and symmetrical iconicity. Through in-depth discussion of the above aspects, this paper could come to the conclusion that the iconicity is very important in the translation of poetry. It is conductive to reach the ideal effect of “the similarity of form and spirit” and “the three beauties”. Key words: the iconicity; poetry; translation

英语翻译专业毕业论文选题

“论文学翻译过程” “语义翻译和交际翻译理论在英汉翻译中的运用” “英语句子成分的省略及汉译” “文学翻译中隐喻的传译” 一、选题范围 1、翻译与文化:可以从宏观和微观两个方面考虑。宏观方面,一般从翻译在目的 语社会文化中的生产、接受、翻译在目的语社会文化中所起的功能等角度讨论, 可以从社会、文化、历史、交际的视角切入。阐述为什么有那样的译文?如严复的翻译,林纾的翻译,傅东华翻译《漂》时为什么使用归化的手段,鲁迅翻译的策略,翻译材料的选择等等。微观方面,可以讨论语言文字所承载的文化内容和内涵如 何在翻译中表达,如文化负载词的翻译策略等。 2、翻译与语言学理论:可以从篇章语言学,功能语言学(如喊韩礼德的系统功 能理论等),对比语言学,心理语言学,交际语言学、文化语言学等方面考虑选题。如功能语言学和篇章语言学中讨论的衔接与连贯及其翻译,也可以讨论他们在英语和汉语中的差别入手,进一步讨论他们在翻译中的处理,主位、述位的推进极其在翻译中的体现。英语汉语对比及其翻译策略等等。 3、翻译与语文学。主要从艺术的角度讨论文学翻译中的问题。 4、应用翻译:主要从特殊用途英语如商务英语、科技英语、旅游英语等方面 讨论在这些特殊领域中涉及的翻译问题如何处理。如旅游宣传资料的翻译等。 5、译文对比:可以是同一篇文章、同一本书,不同的译者在同以时期或不同时 期进行的翻译做的对比,也可以是同一个译者对同一篇文章或书在不同时期的翻 译的对比;可以是翻译技巧等微观层面的对比,也可以是宏观曾面的对比,以探索为什么在不同时期译者回采取不同的策略,有哪些社会的、文化的、政治的、 意识形态的原因? 6、翻译及评论:首先选择一篇长文,一般是文学作品且没有人翻译过,进行 翻译,翻译完后,从上述五个方面选择一个理论视角对自己的翻译进行评论。 7、译者风格。 8、翻译与美学。 二、选题方法: 上述各个方面均可写出几本甚至几十本专著,因此大家从上述方面可以选出一个写作的范围。缩小选题范围:首先是广泛浏览上述各有关方面翻译研究资料,以确定自己对哪方面感兴趣且有话可说,这是缩小范围的第一步。然后在自己感兴

英语文章及翻译

What sports and other activities do you participate in? What kinds of foods do you eat? What kind of people do you spend time with? Your answers to these and similar questions reflect your total health. Health is a combination of physical, mental/emotional, and social well-being. These parts of your health work together to build good overall health. 你参加过什么体育活动和其他活动吗你吃什么食物你和什么样的人在一起你对这些问题或 者类似的问题的回答反映出了你整体的健康状况。健康是身体、心里和社会安宁感的集合。这些健康的部分结合起来搭建了一个完整的健康体系。 Often, good health is pictured as a triangle with equal sides. As shown in Figure 1.1, one side of the triangle is your physical health. Another side is your mental/emotional health, and the third side is your social health. Like the sides of a triangle, the three “sides” of health meet. They are connected. If you ignore any one side, your total health suffers. By the same token, if you make improvements to one side, the others benefit. For example, when you participate in physical activities, you improve your physical health. This helps you feel good about yourself, benefiting your mental health. Activities can also improve your social health when you share them with family and friends. 通常,全身健康可以描述成一个等边三角形。在Figure1.1展示出来,三角形的一条代表身体健康。另外一边代表心理健康,第三条边代表社会性健康。每一条边代表一个健康部分。他们之间有着密切的联系。如果你忽视任何一边,你就不健康了。同样的,如果你改善其中一个部分,其他的部分也会随之受益。举个例子,你去参加体育活动时,这样做能够改善你的体质。这让你自己的身体感觉更好,你的心理健康受益。活动也能够增强你的社会健康,当你和你的家人朋友一起互动的时候。 Do you stay active? Do you get plenty of rest each night? Do you eat healthy snacks? Your answers to these questions will tell you something about your physical health. Physical health is the condition of your body. Physical health is measured by what you do as well as what you don’t do. Teens who want to be healthy avoid harmful substances such as tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. They balance the amount of time they spend watching TV or playing computer games with physical activity. Physical activity includes things such as playing sports, hiking, aerobics, swimming, dancing, and taking a walk. By avoiding harmful substances and being physically active, you can stay physically healthy. In other words, being physically healthy means taking care of your body. 你一直保持积极的状态吗你每天有足够的时间休息吗你吃的食品是有益于身体健康的吗你回答这些问题将要反映你的身体健康的情况。身体健康是通过你自己的身体状况表现出来的。身体健康不仅能通过你做的事情来衡量,也能通过你没有做的事情来衡量。青少年要想有身体健康就必须要远离有害的物质像烟草、酒精和其他毒品。他们用体育运动的时间去平衡他们看电视或玩电脑游戏的时间。体育运动包括做特殊的运动,远足,健身操,游泳,跳舞和做一份工作。通过远离有害物质和坚持体育运动,你可以保持身体健康。另外一种说法就是,要想身体健康就要多运动。 Do you feel good about who you are? Do you know how to handle stressful situations? Do you have a positive attitude about life? Your answers to

论文英文翻译

毕业设计(论文) 英文文献翻译 电力系统 电力系统介绍 随着电力工业的增长,与用于生成和处理当今大规模电能消费的电力生产、传输、分配系统相关的经济、工程问题也随之增多。这些系统构成了一个完整的电力系统。 应该着重提到的是生成电能的工业,它与众不同之处在于其产品应按顾客要求即需即用。生成电的能源以煤、石油,或水库和湖泊中水的形式储存起来,以备将来所有需。但这并不会降低用户对发电机容量的需求。 显然,对电力系统而言服务的连续性至关重要。没有哪种服务能完全避免可能出现的失误,而系统的成本明显依赖于其稳定性。因此,必须在稳定性与成本之间找到平衡点,而最终的选择应是负载大小、特点、可能出现中断的原因、用户要求等的综合体现。然而,网络可靠性的增加是通过应用一定数量的生成单元和在发电站港湾各分区间以及在国内、国际电网传输线路中使用自动断路器得以实现的。事实上大型系统包括众多的发电站和由高容量传输线路连接的负载。这样,在不中断总体服务的前提下可以停止单个发电单元或一套输电线路的运作。

当今生成和传输电力最普遍的系统是三相系统。相对于其他交流系统而言,它具有简便、节能的优点。尤其是在特定导体间电压、传输功率、传输距离和线耗的情况下,三相系统所需铜或铝仅为单相系统的75%。三相系统另一个重要优点是三相电机比单相电机效率更高。大规模电力生产的能源有: 1.从常规燃料(煤、石油或天然气)、城市废料燃烧或核燃料应用中得到的 蒸汽; 2.水; 3.石油中的柴油动力。 其他可能的能源有太阳能、风能、潮汐能等,但没有一种超越了试点发电站阶段。 在大型蒸汽发电站中,蒸汽中的热能通过涡轮轮转换为功。涡轮必须包括安装在轴承上并封闭于汽缸中的轴或转子。转子由汽缸四周喷嘴喷射出的蒸汽流带动而平衡地转动。蒸汽流撞击轴上的叶片。中央电站采用冷凝涡轮,即蒸汽在离开涡轮后会通过一冷凝器。冷凝器通过其导管中大量冷水的循环来达到冷凝的效果,从而提高蒸汽的膨胀率、后继效率及涡轮的输出功率。而涡轮则直接与大型发电机相连。 涡轮中的蒸汽具有能动性。蒸汽进入涡轮时压力较高、体积较小,而离开时却压力较低、体积较大。 蒸汽是由锅炉中的热水生成的。普通的锅炉有燃烧燃料的炉膛燃烧时产生的热被传导至金属炉壁来生成与炉体内压力相等的蒸汽。在核电站中,蒸汽的生成是在反应堆的帮助下完成的。反应堆中受控制的铀或盥的裂变可提供使水激化所必需的热量,即反应堆代替了常规电站的蒸汽机。 水电站是利用蕴藏在消遣的能来发电的。为了将这种能转换为功,我们使用了水轮机。现代水轮机可分为两类:脉冲式和压力式(又称反应式)。前者用于重要设备,佩尔顿轮是唯一的类型;对于后者而言,弗朗西斯涡轮或其改进型被广泛采用。 在脉冲式涡轮中,整个水头在到达叶轮前都被转化为动能,因为水是通过喷嘴提供给叶轮的;而在压力式或反应式涡轮中,水通过其四周一系列引导叶版先直接导入叶片再提供给叶轮(或转子)。离开引导叶片的水有压力,并且以一部分动能、一部分压力的形式来提供能量。 对于低于10,000千伏安的发电站而言柴油机是出色的原动机。其优点是燃料成本低、预热时间短以及标准损耗低。此外,其所需冷却水量极少。柴油发电通常选择用于满足少量电力需求,如市政当局、宾馆及工厂等;医院通常备有独立的柴油发电机,以备紧急情况时使用。 通过电线来传输电能是电力系统中的一个重大问题。而从下面研修目的目的架设输电线路又是必要的: 1.将电力从水电站输送到可能很远的负载中心; 2.从蒸汽站到相对较近负载中心电力的批量供应; 3.出于内部连接目的将电能在紧急情况下从一系统转换至另一系统。 传输电压主要由经济因素决定。实际上,当距离、功率、功耗固定时,输电线路中导体的重量与传输电压成反比。因此,出于经济方面的考虑,长距离传输时电压一定要高。当然,电压超高绝缘成本也就超高,要找到最佳电压必须通过减小导体横截面积来取得绝缘成本与经济节省之间的平衡。 高压传输通常使用配以悬挂式绝缘设备的高架结构。称为路标铁塔用于负载

英语专业翻译类论文参考文献

参考文献 一、翻译理论与实践相关书目 谢天振主编. 《当代国外翻译理论导读》. 天津:南开大学出版社,2008. Jeremy Munday. 《翻译学导论——理论与实践》Introducing Translation Studies---Theories and Applications. 李德凤等译. 北京:商务印书馆,2007. 包惠南、包昂. 《中国文化与汉英翻译》. 北京:外文出版社, 2004. 包惠南. 《文化语境与语言翻译》. 北京:中国对外翻译出版公司. 2001. 毕继万. 《世界文化史故事大系——英国卷》. 上海:上海外语教育出版社, 2003. 蔡基刚. 《英汉汉英段落翻译与实践》. 上海:复旦大学出版社, 2001. 蔡基刚. 《英汉写作对比研究》. 上海:复旦大学出版社, 2001. 蔡基刚. 《英语写作与抽象名词表达》. 上海:复旦大学出版社, 2003. 曹雪芹、高鄂. 《红楼梦》. 陈定安. 《英汉比较与翻译》. 北京:中国对外翻译出版公司, 1991. 陈福康. 《中国译学理论史稿》(修订本). 上海:上海外语教育出版社. 2000. 陈生保. 《英汉翻译津指》. 北京:中国对外翻译出版公司. 1998. 陈廷祐. 《英文汉译技巧》. 北京:外语教学与研究出版社. 2001. 陈望道. 《修辞学发凡》. 上海:上海教育出版社, 1979. 陈文伯. 《英汉翻译技法与练习》. 北京:世界知识出版社. 1998. 陈中绳、吴娟. 《英汉新词新义佳译》. 上海:上海翻译出版公司. 1990. 陈忠诚. 《词语翻译丛谈》. 北京:中国对外翻译出版公司, 1983. 程希岚. 《修辞学新编》. 吉林:吉林人民出版社, 1984. 程镇球. 《翻译论文集》. 北京:外语教学与研究出版社. 2002. 程镇球. 《翻译问题探索》. 北京:商务印书馆, 1980. 崔刚. 《广告英语》. 北京:北京理工大学出版社, 1993. 单其昌. 《汉英翻译技巧》. 北京:外语教学与研究出版社. 1990. 单其昌. 《汉英翻译讲评》. 北京:对外贸易教育出版社. 1989. 邓炎昌、刘润清. 《语言与文化——英汉语言文化对比》. 北京:外语教学与研究出版社, 1989. 丁树德. 《英汉汉英翻译教学综合指导》. 天津:天津大学出版社, 1996. 杜承南等,《中国当代翻译百论》. 重庆:重庆大学出版社, 1994. 《翻译通讯》编辑部. 《翻译研究论文集(1894-1948)》. 北京:外语教学与研究出版社. 1984. 《翻译通讯》编辑部. 《翻译研究论文集(1949-1983)》. 北京:外语教学与研究出版社. 1984. . 范勇主编. 《新编汉英翻译教程》. 天津:南开大学出版社. 2006. 方梦之、马秉义(编选). 《汉译英实践与技巧》. 北京:旅游教育出版社. 1996. 方梦之. 《英语汉译实践与技巧》. 天津:天津科技翻译出版公司. 1994. 方梦之主编. 《译学辞典》. 上海:上海外语教育出版社. 2004. 冯翠华. 《英语修辞大全》,北京:外语教学与研究出版社, 1995. 冯庆华. 《文体与翻译》. 上海:上海外语教育出版社, 2002. 冯庆华主编. 《文体翻译论》. 上海:上海外语教育出版社. 2002. 冯胜利. 《汉语的韵律、词法与句法》. 北京:北京大学出版社, 1997. 冯志杰. 《汉英科技翻译指要》. 北京:中国对外翻译出版公司. 1998. 耿占春. 《隐喻》. 北京:东方出版社, 1993.